Paul McCartney Reveals His Famous James Bond Song Isn’t About Death

“Live and Let Die” has a surprisingly upbeat secret message.

You can’t get more nihilistic than the title Live and Let Die, right? The 1954 Ian Fleming novel was the second literary James Bond adventure ever and later became the first Roger Moore 007 film in 1973. And, although Sean Connery’s Bond had infamously knocked The Beatles in 1964’s Goldfinger, a former Beatle, Paul McCartney, wrote and performed the theme song to the James Bond film that launched a new era for the immortal spy franchise.

But how did Paul write “Live and Let Die?” And isn’t this catchy, and brilliant song a little dark and negative for Paul’s oeuvre? Turns out, that just like there are complex layers to the appeal of James Bond, Paul McCartney’s “Live and Let Die” isn’t actually about death or killing. In a new podcast, McCartney explains his inspiration for writing “Live and Let Die,” and, in a way, it almost makes the song sound like a sequel to “Let it Be.”

The secret meaning of “Live and Let Die.”

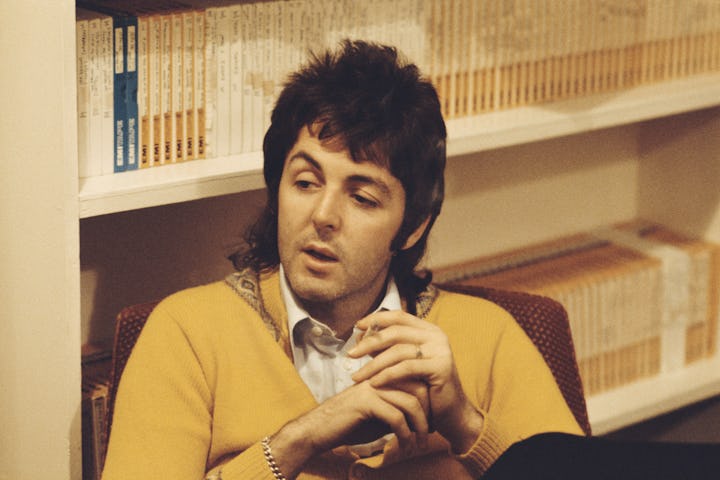

Henry McCullough, Denny Laine, and Paul McCartney in Wings.

In the new podcast series, McCartney: A Life in Lyrics, Paul McCartney is going deep on a ton of his most famous songs with a little help from the poet Paul Muldoon. In the latest episode, McCartney talks about “Live and Let Die.” Somewhat surprisingly, he says the song wasn’t an ode to killing and murder at all. “I didn’t want it to be, now you got a gun, so go out killing people,” McCartney explains. “I just wanted it to be let it go. Don’t worry about it. When you’ve got problems and everything, just live and let die — to hell with it.”

It’s a brilliant revelation that throws new light on one of Paul’s best and most enduring post-Beatles hits. But does this track with the meaning of the film and the novel?

Paul’s James Bond take makes perfect sense

Roger Moore and Jane Seymour in Live and Let Die (1973).

In the podcast, McCartney says “it was always a sneaky ambition to write a Bond song.” Also, Muldoon notes that McCartney did own an Aston-Martin DB5, the famous Sean Connery Bond car at one point in his career, meaning his connection to 007 runs deep. After reading the book quickly, McCartney created a draft of the song “Live and Let Die” in one afternoon.

“Live and Let Die” the song is undoubtedly more famous and better-known than either the 1973 or the 1954 novel, both of which are unpacked in depth in great books like John Higgs’s Love and Let Die. (Or even right here with Fatherly’s Guide to James Bond.)

But, in an interesting connection with Paul’s motivation to write the song “Live and Let Die,” Author Ian Fleming also didn’t believe that his Bond books were about the glorification of killing at all. Throughout the books, including Live and Let Die, Bond frequently questions his purpose, and whether or not carrying out his given mission is even the right thing to do. As Fleming put it in one of the last interviews of his life: “It disturbs him to kill people...he is not without a conscience.”

Fleming also claimed that it was important that although Bond seemed to have a glamorous life, that the author decided to “make him suffer for it.” Contemporary Double or Nothing Bond novelist Kim Sherwood has pointed out there’s pathos embedded within Fleming’s Bond saying: “There’s a kind of vulnerability to his character in the novels that sometimes you don't see on screen, until the Daniel Craig films.”

Vulnerability and being cool as hell at the same time? Sounds a little like Paul McCartney, doesn’t it?

McCartney: A Life in Lyrics is an iHeartPodcast. You can listen right here.

This article was originally published on