70 Years Ago, The Biggest Action Hero Of All Time Made His Shocking Debut

With Casino Royale, Ian Fleming changed the game — forever.

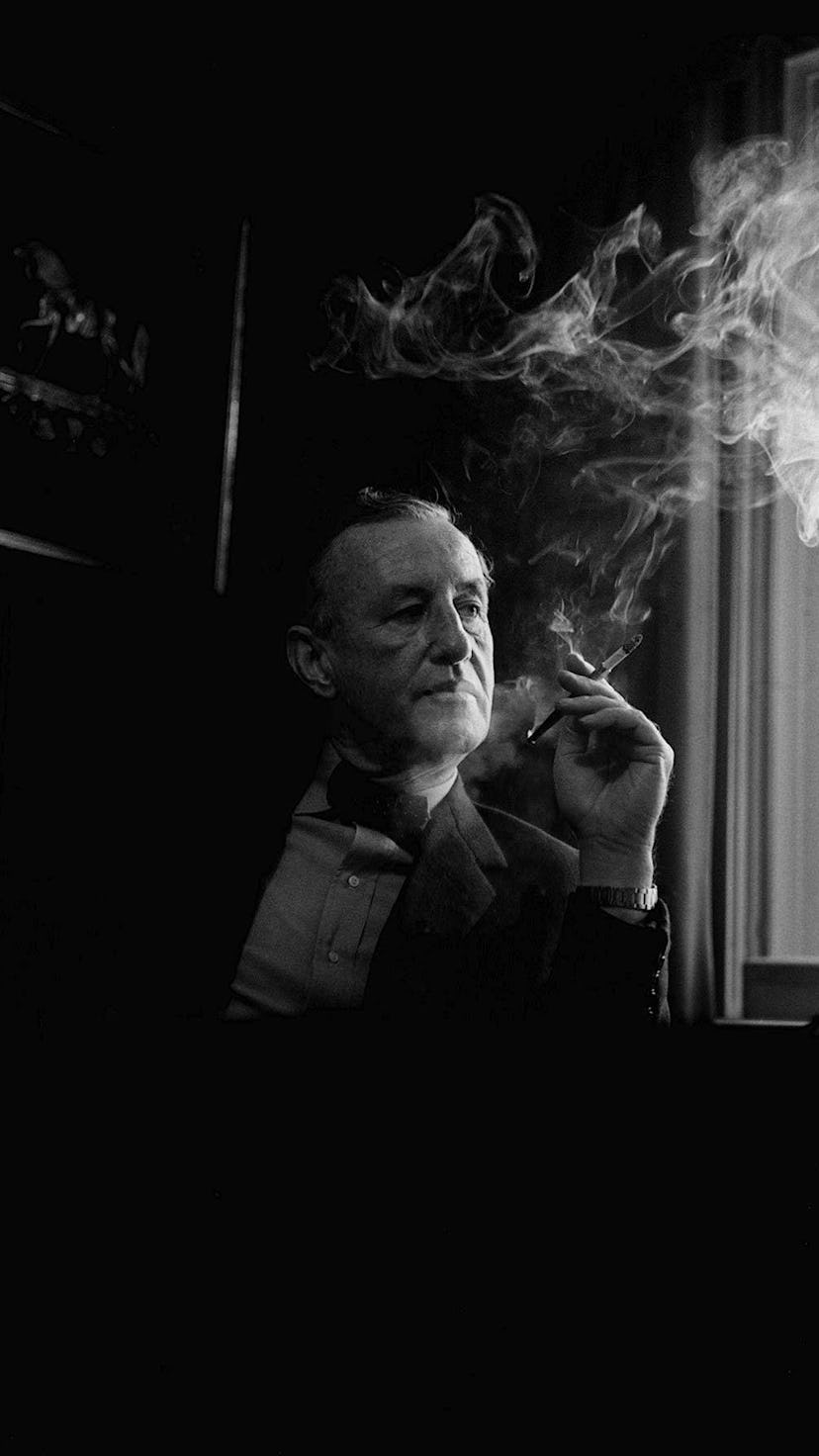

Just before his getting married, at the age of 43, former British Naval officer Ian Fleming sat down at his typewriter, after what many biographers say was five years of procrastinating. In 1952, he was determined to do it. To really write a novel. By 1953 that novel was published. It was called Casino Royale and it not only changed Fleming’s life but shocked and thrilled the entire world. The film series that began in 1962’s Dr. No with Sean Connery as James Bond is certainly more visible, but without Fleming and his books, the phenomenon of Bond simply wouldn’t exist. And, in many ways, the first Bond book, is still the best. Published seven decades ago on April 13, 1953, Casino Royale created a new kind of action thriller — one that wasn’t afraid to actually mock its male protagonist.

If your only experience of Casino Royale is just the 2006 Daniel Craig movie, know this: Of all the Bond films it’s probably the only handful of the films that both closely follow the plot one of the source material and actually capture the tone and meaning of the book. But the biggest difference between the 1953 novel and the 2006 film is simple: In 2006, the depth and pathos that Daniel Craig’s Bond felt seemed subversive to the rest of the film series to that point. But, in 1953, that’s just what the book was about.

First editions of Thunderball, Casino Royale, and Diamonds Are Forever.

Casino Royale is a spy novel, but it’s a deadly serious one, a world in which the thrills are just as grotesque as they are exciting. When Bond is almost killed by a small bomb in chapter 6, he doesn’t dust himself and straighten his tie, he nearly passes out and throws up. And, when he loses all his government’s money at the Baccarat table at the end of chapter 11, he doesn’t clench his jaw and make a joke. He feels “beaten and cleaned out.”

James Bond loses a lot in Casino Royale, far more than he wins. In fact, if you’re just tallying his victories in general, it’s actually hard to find one single thing that truly goes his way. Yes, he’s bailed out of his gambling losses by the CIA, and, as in the film, is able to defeat the evil Le Chiffre at the baccarat table. The difference between the novel and the film is the tone. After Bond is kidnapped and tortured, he actually buys some of the arguments made against his line of work: Maybe patriotism is weird. Maybe being a macho killer who works for the government is wrong. As Bond says “...when one’s young, it seems very easy to distinguish between right and wrong, but as one gets older it becomes more difficult.”

This isn’t an argument for moral relativism or an anything-goes mentality. Instead, what Bond is saying is that it’s arrogant for him to presume to know the people he’s going after are evil and that he’s good for going after them. In this way, Bond is a true anti-hero, and the novel Casino Royale, a kind of indictment of the male ego. While it’s true Bond is a sexist, but he doesn’t benefit from his sexism, and after reading the book, no sensible person would believe the message was that men of the 1950s were doing just fine.

Yes, there is some exciting spy action. Yes, the fights are great. Yes, Bond is cool, if much chillier than his movie persona. But, the most striking thing about Casino Royale is that its structure is closer to a slimmer version of Hemingway’s Farwell To Arms. Bond’s convalescence takes up a good chunk of the final third of the book. After that, the book becomes a tragic love story, in which Bond and Vesper really, really want to be happy together, but are just so broken and depressed from their lives in espionage that they can’t even function as a couple. Despite all of this, Bond really wants to marry Vesper, but of course, he can’t, because of a very famous, utterly shocking, and tragic ending.

It’s worth mentioning again that this is the first James Bond novel. The character doesn’t sleep around with a bunch of people — he only hooks up with Vesper after their harrowing mission is over. Bond has some racy fantasies about her, but in terms of their actual intimacy, the films are much soapier. The arch surreality that Bond would later embody simply doesn’t exist in Casino Royale. In the much later books, some of that Connery swagger starts to emerge, partly because Fleming lived to see both Dr. No and From Russia With Love made into films.

But, in the beginning, in Casino Royale, the Bond persona is brittle and fraught with psychological chaos. What makes the Bond of this novel so relatable, is that he’s not smarter than his enemies, and he’s not more charming than other men. Most of his adventure, whether good or bad, is just all down to circumstances. Bond becomes an everyman because Fleming makes it clear that he can lose. And in this way, Fleming created the greatest action hero of all, one that has never quite been captured on screen, except of course, to a very large degree, by Daniel Craig.

Before he died in 1964 — just two weeks before the debut of the film version of Goldfinger — Fleming gave a lengthy interview to Playboy, which has been lavishly republished in Paul Duncan’s recent edition of the Taschen coffee table book The James Bond Archives. In that interview, you will find this odd insight from Ian Fleming about the creation of James Bond for Casino Royale: “He just came out of thin air...he is a meld of qualities I noted among various people.”

Bond is different than other action heroes for this exact reason. We might think we get the character because of the mega-popular films, but if you look back at Fleming’s first book there’s much more to 007 than Martinis and poker. And the reason that James Bond endures isn’t that Casino Royale is a really fun book, it’s more to do with the enigma of the character himself. Because Bond is so clearly a composite of some of the rawest and strangest aspects of men, he’s harder to truly understand at first blush.

And so, maybe one of the reasons we still care, seventy years later, is that despite all the books and all the movies, this secret agent is still very much a mystery —not only to us but to himself, too.

Check out new editions of the Ian Fleming books from Harper Collins right here. And also snag these gorgeous illustrated editions from the Folio Society, here.

This article was originally published on