The 5 Words Mister Rogers Used To Help Kids Learn

Want to build a bridge to better communication with children. Use the building blocks that Fred Rogers Used.

The way Fred Rogers communicated has been the subject of much examination. He was deliberate without being rigid. He was quiet without being passive. He was empathetic without being paralyzed. How did he achieve this? He worked hard at his scripts. In his archive in Pennsylvania, stacks of scribble-covered papers pay tribute to Rogers as an exacting self-editor. The printed scripts contain large words that were then carefully crossed out and replaced with more comprehensible language. After all, Mister Rogers, the titular character and de facto mayor of Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood, spoke mostly to coma and to the millions of children watching in their homes. He understood that they hung on his every word. But what were those words, exactly?

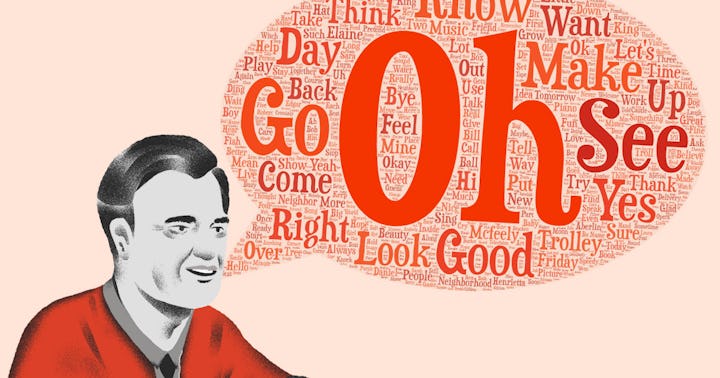

We know that Fred Rogers created a space of encouragement and kindness, but by examining which words he leaned on, we can learn to construct meaning and child-friendly lessons out of Mister Rogers’ rhetorical building blocks. To that end, Fatherly analyzed the closed-captioning text for 30 representative episodes of Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood pulled from the 31-season run. After throwing out common words (conjunctions, articles, pronouns), we looked at the frequency of word use. The results show that Mister Rogers was not merely a calm and affirming character. He insisted on exploration and action. He demanded curiosity. And he responded to it as well.

A breakdown of Mister Rogers’ most frequently used words provides a window into a spectacularly effective communication strategy. And his top five words by usage are a great place to start.

5) “Know”

Used 457 Times

It makes sense that a cornerstone of educational children’s programming like Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood would make knowing central. To know is to be educated and to understand. But for Fred Rogers, the verb was dynamic and transactional. The knowing went both ways. Yes, he wanted his young audience to know the world through the lens of their neighborhood, but he also wanted to know his young audience.

In Mister Rogers’ world, “know” is frequently part of a question. Rogers doesn’t assume a child’s knowledge or demand that they know much of anything. But he uses knowing to pique curiosity: “Did you know…?” or “Do you know…?” has the power to draw children into discovery. The word places a primacy on the act of seeking an answer, and assures children that the world can be known. In that way, Rogers could inspire kids to be curious themselves, while also reassuring them that there was an answer to be found. Rogers is often remembered for the emotional resonance of his work, but he was not just interested in feelings. He loved to empower children with facts. The feeling of security he inspired emerged from the sense that Mister Rogers was never evasive. He wanted his audience to know what he knew.

4) Make

Used 469 Times

Many viewers of Mister Rogers Neighborhood will remember the factory visits. Viewer were often taken to various spots near the WQED studios in Pittsburgh to learn how things were made. We were given a glimpse into the process of making so we could see that the things in our homes didn’t simply appear there fully formed. There were steps in making paper, or violins or rubber balls.

Rogers loved the idea of manufacturing. In the Neighborhood of Make-Believe the puppet Cornflake S. Pecially calls himself a man that manufactures. He makes chairs. And there are often plots that revolve around Cornflakes’ chair-making factory. Cornflake was one of the first puppets Fred Rogers ever made.

But aside from showing his young viewers how things were made, Mister Rogers often invited children into his kitchen, to sit with him a the table and craft. The projects would usually involve materials found around the home — a protean form of upcycling before the term was even coined. And happily, there were rarely right ways in which to build the crafts. There was always room for creativity. The beauty was that the word “make” came to encompass both industrial processes and creative processes. The act of creation, rather than the forum in which the act took place, was the thing of interest.

3) Go

Used 609 Times

Fred Rogers was calm, measured and reassuring, yet his third most frequently used word was an exhortation to motion. One doesn’t necessarily equate Mister Rogers with action, but when you watch his episodes with the word “go” in mind, it’s suddenly clear just how restless the program is. The camera is always shifting and Mister Rogers and his viewers rarely stay in one place for too long. Again, this is very much by design. Kids do not have long attention spans. To keep his audience engaged, Rogers had to move quickly.

Consider the fact that the show begins with the act of arrival and ends with the act of leaving. Viewers don’t just happen upon Rogers sitting idly in his home.Viewers catch him between here and there. And while they’re with him, they go. Viewers go to factories and businesses. Viewers go to the Neighborhood of Make-Believe. Viewers go outside or to the kitchen.

Yes, as children, we sat at home watching. But we were watching a man being active. Mister Rogers modeled active behavior through the television — an entirely unique trick.

2) See

Used 675 Times

A close second to “go” is “see.” There’s likely a reason that the two words are used nearly the same number of times in these episodes. Because if you’re going to go, you’re also going to see. “Let’s go see … ,” is a common refrain on Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood. But there’s more to “see” than the activity that happens once viewers reach their destination. Interestingly, the word “look” is used about half as much as “see” (346 times) over the same number of episodes. “Watch” is used considerably less (59 times). What’s the difference? If Rogers just wanted kids to regard something, wouldn’t these words be more likely to have similar rates of use?

Not really. Watching is passive. Looking is fairly passive. Seeing is active. When you see, you notice. When you see something, an object or an event, you’ve been able to capture and retain something of its quality. In order to know something, you have to see it. Seeing is part of learning in a way that watching is not. Fred Rogers didn’t want children to watch his show. He wanted them to see inside his house and his neighborhood.

1) Oh

Used 918 Times

At first blush this seems like a mistake. Isn’t the frequent usage of this two-letter exclamation more of a rhetorical quirk than a choice? Doubtful. It’s unlikely he would have allowed “oh” to colonize his sentence. There’s little reason to believe that “oh” was anything but a measured choice. And, once you think about it, the prevalence of “oh” begins to make sense. In fact, it feels kind of profound. The word “oh” communicates recognition and realization. It is a hook on which a conversation can hang. And Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood was a conversation.

But “oh” isn’t just an acknowledgment. It’s a declaration of wonder and surprise. “Oh” is also “Oh!” And “Oh!” is a big-hearted feeling. It can mean joy or love. It contains about as much as two letters can. In a sense, “oh” can hold the entirety of the Mister Rogers neighborhood in one fine syllable.

But when taken with the other four words in Mister Rogers top five words, “oh” becomes an exclamation for a fine life motto that someone might stencil on their wall:

Know. Make. Go. See…. Oh!

It’s Fred Rogers final command to us — learn something of the world, build something useful that lasts beyond you, move beyond the places you know, make an effort to notice the world around you and never be afraid to show your joy in it.

Know. Make. Go. See.

Oh!

This article was originally published on