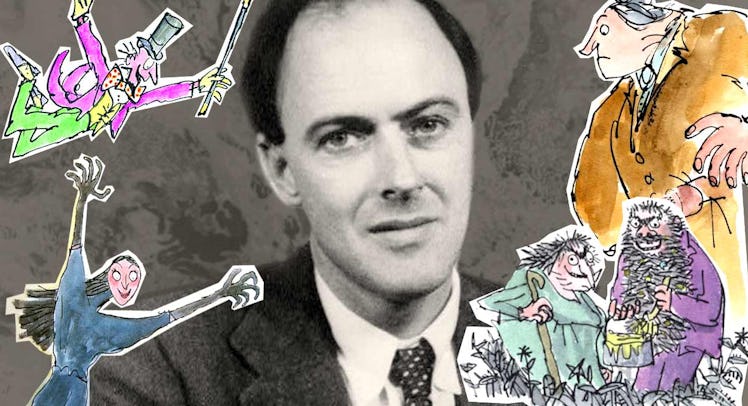

How Roald Dahl’s Monsters Took Over the World

Roald Dahl didn't just give us Wonka and Matilda. He gave us a world of cruel discipline too.

Roald Dahl was a constant companion as I grew up. When I was very young, I toured chocolate factories with Charlie and hung out with James and his insectual friends. And I feared the exquisitely described adult tormentors of Dahl’s literary children: Miss Trunchbull, Spiker, and Sponge, the headmistress at Sophie’s orphanage in The BFG. These characters were expertly cruel and vividly rendered. As I got older, I read Dahls’s short stories for adults. The Hitch-Hiker, about a pickpocket of great skill, inspired a decade’s worth of shoplifting. Then I discovered the very adult fiction, stories like The Great Switcheroo, which introduced me to the concept of wife-swapping. Naturally, I loved all of these books. Still, I don’t return to them. The book I return to — and think about when I read to my sons — is Boy: Tales of Childhood, a collection of bleak autobiographical essays that has haunted me for decades.

Boy chronicles Dahl’s unhappy childhood, starting in 1920 with the death of his older sister and his one-armed father then loitering in depressing schools full of evil educators. Reading Boy was, to say the least, eye-opening. I had never heard of such cruelty inflicted on children by adults or by other children and I had been fortunate enough never to have been treated unjustly. Adult cruelty to children was something I had experienced second-hand, disproportionately in the works of Dahl. Remember little Bruce Bogtotter being forced to eat an entire chocolate cake in some sort proto-David Fincher torture scene in Matilda? Dahl’s young characters end up in lose-lose situations that I chose to believe, when I was small, were fictional. They weren’t.

Read more of Fatherly’s stories on discipline, behavior, and parenting.

What I saw in the pages of Boy is how thin the veil was between the cruelty exhibited by Dahl’s fictive villains and the cruelty exhibited by his actual tormentors was. And how, through the massive popularity of his novels — and their many movie adaptations — Dahl’s childhood monsters have become our collective childhood monsters. As a boy, Dahl viewed most adults as dangerous beasts and his fellow students as eager kapos. As an author, he created a world, touched by fantasy, in which this was so. And that is the world of our collective imagination. And that is both a great service and a brilliant revenge.

Starting in 1923, when he arrived at the Llandaff Cathedral School, Dahl chronicles a series of canings, beatings and humiliations in ever more intricate and sadistic detail. Even the first caning he chronicles, meted out after he and four of his friends placed a dead mouse among the gobstoppers in a candy store, is baroque. Mr. Coombes, the headmaster, carefully lines the boys up and canes them — six strokes each with a thin cane, as the candy seller eggs him on.

All I heard was Mrs. Pratchett’s dreadful high-pitched voice behind me screeching, “This is one’s the cheekiest of the bloomin’ lot, ‘Eadmaster! Make sure you let ‘im ‘ave it good and strong!”

Mr. Coombes did just that. As the first stroke landed and the pistol-crack sounded, I was thrown forward so violently that if my fingers hadn’t been touching the carpet, I think i would have fallen flat on my face…. It felt, I promise you, as though someone had laid a red-hot poker against my flesh and was pressing down on it hard….

And thus begins the long miserable catalogue of beatings and abuse that follow our lacerated protagonist from Llandaff — his mother hears about the canings and pulls him — to the more brutal St. Peter’s School. There’s a chapter called Captain Hardcastle, about a red-haired Great War veteran who taught at that school, suffered from PTSD, and who hated boys in general and Dahl, in particular. The chapter is absolutely gutting and it really captures the total hopelessness that children like Dahl came to know all to well.

In one scene, Dahl has broken the rules of study hall by asking a neighbor for a nib (has to do with pens.) Hardcastle has rather trapped him in that old sadist’s pincer, between a false confession and protestations of innocence, read, or course, as insubordination. Dahl has received a summons to be caned and is caught in the exact same trap with the Headmaster.

“What have you got to say for yourself?’ he asked me, and the whie shark’s teeth flashed dangerously between his lips.

‘I didn’t lie, sir’ I said, ‘I promise I didn’t. And I wasn’t trying to cheat.’

‘Captain Hardcastle says you were doing both’ the Headmaster said. ‘Are you calling Captain Hardcastle a liar?’

‘No, sir. Oh no, sir.’

‘I wouldn’t if I were you.’

‘I had broken my nib, sir, and I was asking Dobson if he could lend me another.’

That is not what Captain Hardcastle says. He says you were asking for help with your essay.’

It basically goes on like this, spider wrapping the fly in silk, until the Headmaster beats Dahl. And then it gets worse as Dahl moves to Repton, a preparatory school in the Midlands, and is exposed to a hierarchical hazing system called “fagging.” “[Older kids] could summon us down in our pyjamas at night-time and thrash us for….a hundred and one piddling little misdemeanours — from burning his toast at tea-time, for failing to dust his study properly, for failing to get his study fire burning in spite of spending half your pocket money on firelighters, for being late at roll-call, for talking in evening Prep, for forgetting to changing into house shoes at ‘six o’clock,” writes Dahl. “The list was endless.”

The slow-motion enactment of sadistic discipline, the circling in words of the victim by the perpetrator, the capricious punitive measures mark all of Dahl’s villains. Whether it is Miss Trunchbull’s physical assault of her students in Matilda or Sophie’s miserable headmistress in The BFG or James with his evil aunts, Spiker and Sponge in James and the Giant Peach, or George’s terrifying Grandma in George’s Marvelous Medicine, Dahl has brought his childhood experience through his pages to my childhood experience and now, through me, to my children’s.

Now, as I work through Dahl’s books with my own sons — who have yet to read Boy — it’s impossible to forget what I’ve learned. It’s impossible to see the books as being about whimsy when it’s so plain that they are, in fact, exorcisms. What Dahl sets out in these pages isn’t just abuse but the intergenerational and institutionally supported transmission of that abuse and victimization from adults to children and then to children to children.

Girded in fanciful names, these are the characters my children fear most from Dahl’s books and whose ingenious demises at the hands of their victims they cheer. They are the reasons my kids ask for Dahl every night and why children around the world ask for Dahl too. I pray that my own children, all children, never experience, first-hand, the abuse and fear Dahl did but by reading his vivid stories, they understand it. It isn’t their past but it is theirs to fear and it is theirs to learn from. It was an option, sadly, never open to the author. “I am sure you will be wondering why I lay so much emphasis upon school beatings in these pages,” Dahl writes in Boy. “The answer is that I cannot help it…I couldn’t get over it. I never have got over it.