30 Years Ago, One Children’s Book Invented A New Genre — And Got Banned 11,000 Times

The Giver has never stopped being relevant or controversial.

Dystopic fiction is one of the most popular genres among young readers. They come at a perfect time in a preteen's life, easy for kids to identify with as they begin to question authority and rebel against the norm in their own lives. Today, this revolutionary vibe is highlighted in plenty of books aimed at children and tweens, but it wasn’t always that way.

When The Giver was first published in 1993, it stood alone in a burgeoning field that previously didn’t exist. At least not the way we think of now. The young adult market didn’t have a name yet, as books jumped tonally from children to adults in a flash. Even less had themes as mature as The Giver, directed towards an audience who needed to read these words to encourage personal growth within themselves. A dash of rebellion combined with a coming-of-age story, thirty years ago, The Giver broke literary ground to become a classic that remains as controversial now as it was thirty years ago. Before Katniss picked up a bow and arrow or Tris loaded her rifle, Jonas rode a sled.

The Capacity to See Beyond

Jonas has just turned twelve, the age where he is assigned the task he will do for the remainder of his life. He and his family live in a seemingly utopic society of “precise” inoffensive language and systemized habits, a flat monochromatic world of “sameness.” While Jonas’ friends are chosen for careers best suited to their abilities, the adolescent is surprised when the Chief Elder reveals he’s been appointed to the most esteemed position in the community – The Receiver. Exempt from all rules, Jonas starts under the tutelage of the current Receiver, an elderly man with the gift (and curse) of memories from generations ago, taken from them in order to achieve this dubious paradise.

Now rechristened as The Giver, his sensations and feelings are passed onto his young apprentice, who revels in the pleasurable sentiments of sunlight, colors, and love. But, with these positive feelings comes the negative, as Jonas now too wears the burden of physical and emotional pain, hunger, and the savagery of how humans lived years prior to this sterilized world. This journey leads them to a revelation of how to help restore the conscience of their community, a road that may lead Jonas to make the ultimate sacrifice.

The original cover for the first edition of The Giver, designed by Cliff Nielsen

Lois Lowry was inspired to write The Giver based on interactions with her aging parents, who relieved fragmented memories of their past with their children as they withered peacefully in nursing facilities. The idea popped into Lois’ head - What would happen if something existed that took memories away from people to make their lives more peaceful?

Writing books for children was never in the purview of Lois, whose first book was published when she was 40. Her work never shied away from tough topics, told through the eyes of young protagonists coming to terms with unjust worlds. Whether that be the growing pains that middle-school-aged Anastasia Krupnik suffered through her nine books, or standing up against an oppressive authority like in Number the Stars, these worlds often collide simultaneously across Lowry’s catalog.

The stagnant world that Jonas dwells in is the counterpoint to Lowry’s themes of memory, freedom of will, and individuality. Besides the erasure of feelings, uniqueness, and racial “color blindness,” the arts no longer exist in this world either – meaning no books, music, or art. An unnamed society of brutalist grey architecture devoid of personality, while controlled by an overbearing political authority, has readers debating to this day over how to interpret its political allegiance. But the message has never been intended to be overtly partisan. The oblivious comfort of its residents is set in a place that doesn’t feel too alien to a reader and firmly seats them into a place they can relate to, empathizing with this cautionary tale of what happens when human connection is lost and people can’t understand who they truly are because they lack the substance to do so. “We need those memories,” Lowry once explained, “because they make up who we are.”

The Giver kicked off the dystopic genre of young adult fiction, an unintentional side effect that made way for The Hunger Games and the Divergent series among others. Its roots and influence are clear in so much best-selling fiction, yet its own road to prominence was turbulent against outrage from some parents and educators.

Taking the Gift Back

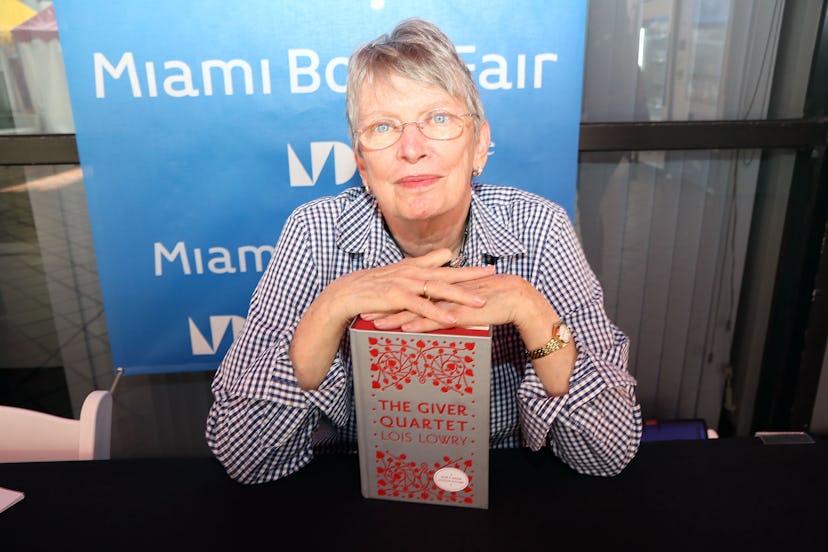

Lois Lowry refuses to let The Giver be banned anywhere

Despite critical acclaim and accolades, The Giver landed in hot water almost immediately. It has remained a position high atop the American Library Association’s most frequently challenged and banned book list, an honor it shares with other classics like The Catcher in the Rye, and The Bluest Eye,

In 1994 - The same year the book won the Newbery Award - The Giver faced its first opponent when it was temporarily banned in a California school district over concerns about mature content. This title has been challenged and outright banned in schools across the country for decades, including one instance where a school required parental permission to read the book. Another district in Colorado challenged the book in 2001 when a father claimed content like this had the potential to contribute to assaults on schools.

Infanticide, euthanasia, eugenics, brutality towards people and animals, and mature imagery are scattered throughout the book among other topics. It’s a stark change for preteen readers who may still be accustomed to the shenanigans of Captain Underpants or Matilda and not prepared for real-world consequences. Yet, many schools fought back against the allegations, stating The Giver was a bridge for young readers to move from one range of books into an older bracket. Some of the scenes depicted are shocking at any age and are admittedly dark, but according to Lowry are important to their development and to generate discussion. “When they read about people experiencing those hard things, they rehearse how they would react, feeling it without having to truly feel it yet. It serves a valid purpose for them.” Indeed she echoed these exact feelings to Fatherly in a 2018 sit-down interview when she said: “I don’t think we’re doing children a favor if we protect them from unpleasant facts.”

Since its publication, The Giver has been challenged over 11,000 times to be banned in schools and libraries, winning some battles and losing others, but typically for a brief time period. Lowry learned not to worry as much about the criticism but remains staunch in defending her work as a necessary piece of literature. “The world portrayed in The Giver is a world where choice has been taken away. It is a frightening world. Let’s work hard to keep it from truly happening.”

Children are often more resilient than we give them credit for because a problem adults deem insignificant is earth-shattering to an adolescent. We’ve seen it in places like Beverly Cleary’s Dear Mr. Henshaw, Katherine Paterson’s Bridge to Terabithia, Wilson Rawls's Where the Red Fern Grows, and other bittersweet novels that came before them. Books like these and The Giver are a gateway for children into a new way of interpreting the world and finding meaning as they grow up. It’s an important experience that can be scary and invigorating, just like going downhill through deep snow on a sled.

The Giver was followed by three additional books - Gathering Blue, Messenger, and Son, comprising The Giver Quartet. It was also adapted into a film in 2014.

This article was originally published on