This Overlooked Children’s Classic is Perfect For Raising Resilient Kids

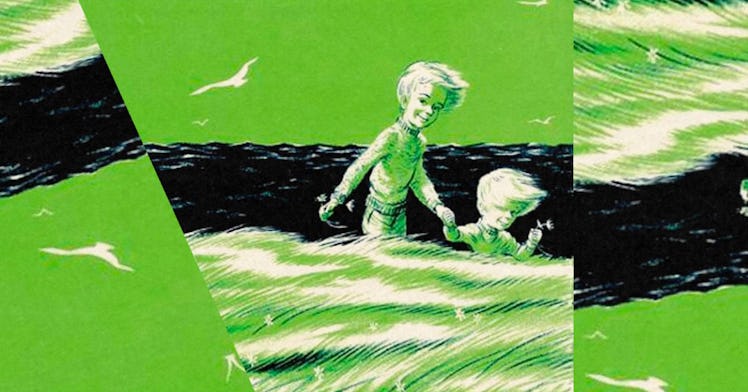

Robert McCloskey wrote enduring children’s classics like ‘Make Way For Ducklings’ and famously, a story about a little girl and blueberries. But the book that came after — ‘One Morning in Maine’ — is his true masterpiece.

I love contemporary children’s storybooks. We live in the age of hilarious characters like Elephant and Piggie from the Mo Willems books, and empowering, happy books like the 2017 slam dunk by Amy Krouse Rosenthal and Paris Rosenthal; Dear Girl. But, just like a lot of parents, I donate a lot of hours reading my toddler children’s picture books that have been around since before my parents were kids. And, now, my daughter’s deep, deep love of one Robert McCloskey book has made me realize the guy who wrote Blueberries for Sal and Make Way For Ducklings also wrote a brilliantly playful, but deceptively profound book about managing expectations. It’s also the sequel to Blueberries for Sal, and there’s a chance you’ve never heard of it. It’s called One Morning in Maine and it’s just as excellent as it was when it was published in 1952. It’s also one of the best books I’ve ever read about recontextualizing disappointment.

At a glance, a parent with a hyper-kid 21st century might skip One Morning in Maine. There’s a lot of sitting around and talking, and OMG there are so many words on each page. But, I’d argue the sentences in One Morning in Maine are not only clearer than 90 percent of other children’s books, but they’re also actually cleaner and better than most sentences I will personally ever write. This is the first line:

One morning in Maine, Sal woke up. She peeked over the top covers. The bright sunlight made her blink, so she pulled the covers up and was about to go to sleep when she remembered “today is the day I’m going to Buck’s Harbor with my father!” Sal pushed back the covers, hopped out of bed, and hurried out into the hall.

The high stakes of going to Buck’s Harbor on a grocery errand are pretty much the big plot point of the entire book; a small family adventure Sal is looking forward to immensely, mostly because she knows it will result in ice cream cones. But, right after Sal runs out into the hall and helps her baby sister Jane, there’s a plot twist: Sal’s tooth is loose. OH SHIT. Now, Sal is freaking out. If she’s got a loose tooth, the day is ruined, right? Wrong! Her mom assures her that having a loose tooth is actually a good thing because it means she’s growing up. (For those paying attention, this is the same hot mom who took Sal to Blueberry Hill a few years earlier.)

Because Sal’s family lives in a time travel bubble where it’s okay to let a kid walk alone down the shoreline by herself in the morning, the book gives us a few wonderful pages about Sal walking outside, thinking wistfully about other animals and how they might — or might not – lose their teeth. The motivating factor here is that Sal’s mom told her that when you lose a tooth, that it’s a kind of passport to “secret wishes.”

Listen. Secret wishes are really fucking important to little kids. The idea that you trade an object and get a relatively simple thing in return is one of the simplest and most innocent ways a little kid expresses want. Assuming your toddler or preschooler is not an extreme Buddhist, it’s good for them to want stuff, to express preferences. Sal’s wants an ice cream cone, though because she’s a smart kid, she’s evasive about saying it out loud directly. When Sal’s tooth falls out and is lost in a muddy pool of clams (ANOTHER PLOT TWIST!) she’s suddenly worried that she won’t be able to get her secret wish, because the talisman of that secret wish —the loose tooth — is suddenly gone.

But, resiliently, Sal notices a dropped-out feather from a seagull, and after a philosophical negotiation with her dad, decides, yeah, sure, dropped-out seagull feathers are pretty much like loose teeth; they to can grant secret wishes. By the time they’re on their way to Buck’s Harbor, now with toddler Jane riding along, Sal feels pretty confident that her secret wish will come true after all. Which is why the third plot twist is so subtle and brilliant. In order to get to the grocery store, Sal’s dad has to take a little boat across the bay. Normally, this boat is powered with a small motor, but today, “the outboard motor coughed and sputtered and wouldn’t start.” Heroically, Sal’s dad does not lose his shit (I might have) but instead just takes up the oars and rows the boat to Buck’s Harbor, the big/little destination, the very realistic Oz of this particular journey.

This moment matters because when Sal’s dad takes the motor to the mechanic at Buck’s harbor, Sal starts wondering how a motor will grow a new spark plug. This is exactly how little kid logic works; a tooth is like a feather is like a spark plug. And though Sal is surprised for a nanosecond when the mechanic just pulls out another spark plug from the shop, it’s how she regards the discarded spark plug that is brilliant: She picks it up and a makes a wish on it for her baby sister Jane. All the discarded objects become wishes, and Sal and Jane both get ice cream cones.

Even the mild disappointment Sal’s dad must have felt over the time lost by the bum spark plug is smoothed over by Sal’s worldview. The story begins with a shock to her system — a loose tooth! — we see her lose it, and then, a boat motor threatens to screw up the whole day. But everyone keeps it cool, uses their imagination. Part of the reason why this all works is that these conflicts are presented peacefully, and as matters-of-facts.

My daughter loves the manic energy of newer kids books but the peaceful meditative quality of One Morning in Maine captures her attention longer, and I’d argue, affects her more deeply. My daughter sits quietly for the entirety of this book, and it’s not a short book; as I hope I’ve made apparent, a lot of shit happens. Its ordinary shit, but it’s the important everyday things that make up a child’s entire world. This small story is like taking a Yoga class with your kid sitting on your lap. You’ll feel better after you read it, you’ll breath deeper, and maybe, just maybe, look up at the sky and wonder about the secret wishes of seagulls again.