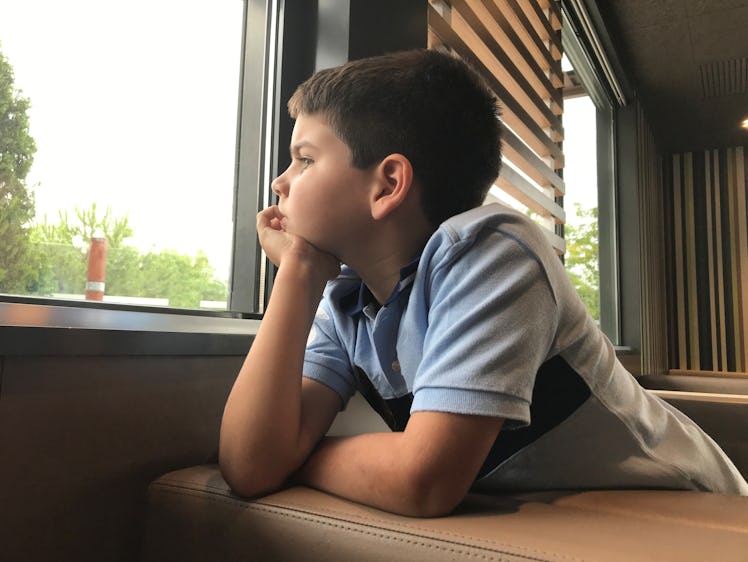

The Tragic Decline Of Bored Kids And Dangerous Play

Modern childhood leaves little time for free play. Experts think kids are suffering because of it.

In the 1980s, psychologist Louise Bates Ames wrote a series of books explaining the stages of child development. Most of the content still holds up today, aside from some laughable exceptions. In Your Five Year Old, for example, Ames writes that by the age, children should be able to run errands for their parents, find their own way to the store, select items, and get correct change. To modern parents, who are expected not only to supervise but curate and direct their child’s activities, this scene is nothing if not bizarre.

Ames’ description of the ability of a Kindergartner sounds straight out of Tom Sawyer and movies like The Sandlot — a good old-fashioned childhood. Your Five Year Old is a historical artifact proving kids were once autonomous creatures with few directives other than make it home for dinner. They ran the neighborhood, meeting up with friends by chance for pickup ballgames and resolving scuffles without adult intervention. Without constant access to the internet, they were left to kick dirt around and argue over questions that weren’t yet Googleable.

The aimless, wandering childhood of Twain or Ames, doesn’t really exist anymore — at least for a large subset of mostly middle- and upper-class American kids. They spend more time than ever in school, on homework, and in enrichment activities. The little time that’s left after academics is spent on organized sports or other activities where adults are calling the shots. Between the early 80s and 1997, children’s play time had decreased by 25%. Today, the average kid only spends 4-7 minutes outside doing something unstructured each day, according to a report issued by the national parks and recreation association.

Part of this can be blamed on a culture of intensive parenting, which asks parents to provide near constant entertainment for their children. “They don’t really have time to be bored, and they don’t really have time to initiate their own activities,” says Peter Gray, Ph.D., a psychologist, professor emeritus at Boston College, and author of the book Free to Learn: Why Unleashing the Instinct to Play Will Make Our Children Happier, More Self-Reliant, and Better Students for Life.

In fact, a 2019 study of more than 3,000 parents found that the most common response to a question about how to address a child’s boredom was to enroll them in an extracurricular activity. Playing outside or with friends ranked 6th and 7th respectively, only after responses like “find an activity that interests the child,” and chores or homework.

This kind of childhood, spent being shuffled from one activity to another, leaves little time to be alone and little opportunity to make independent decisions or mistakes — like getting lost and finding the way back. Experts are starting to think this loss of freedom is a problem. The lack of unstructured time, they warn, decreases levels of creativity and problem-solving, and influences poor educational outcomes and skyrocketing levels of depression, anxiety, and childhood suicide.

Boredom Leads to Creativity

In a 2019 study, an Australian research team found that boredom can be creative fuel. They found that people who completed a boring task (sorting beans) were more creative and productive in idea generating activities than participants who completed an engaging task (coming up with excuses for being late). Those findings echo a 2012 study where researchers found that “engaging in an undemanding task during an incubation period led to substantial improvements in performance on previously encountered problems.” In other words, a wandering mind can help a person think of better and more creative solutions to problems.

Yes, activities like organized sports, art classes, and music lessons are beneficial. But they don’t provide the same opportunities for learning, says Wendy Mogel, Ph.D., a clinical psychologist, host of the Nurture vs. Nurture podcast, and author of Voice Lessons For Parents: What to Say, How to Say It, and When to Listen.

“Activities can build skills,” she says. “But it does not promote independence, and it actually erodes self-confidence.”

When Play Becomes Risky, Kids Learn

In 2018, the American Academy of Pediatrics published a report urging pediatricians to prescribe play during well visits. The authors described how increasing emphasis on academic readiness led to more and more hours in school and enrichment programs, robbing kids of the play time so critical to development.

“Part of the reason that human beings have this long period of childhood is because it takes time to learn how to take control of your own life, decide what you really want to do, and then make that happen,” explains Gray. “And all of this is what play is for. Ideally there should be no adults around.”

Even risky play (or what some parents would consider dangerous play) can be beneficial. Mogel points to the work of Norwegian early childhood education professor Ellen Beate Hansen Sandseter. Her research elucidates six kinds of risky play that promote independence in children: playing at great heights, traveling at great speeds, playing with dangerous tools, playing with dangerous elements like fire or bodies of water, rough and tumble aggressive play, and play where there’s the potential to get lost.

These kinds of play help children develop a sense of mastery over these situations, which Sandseter theorizes helps prevent them from being anxious and fearful of them as adults. Her 2011 article examining the evolutionary role of risky play concludes: “We may observe an increased neuroticism or psychopathology in society if children are hindered from partaking in age adequate risky play.” Many experts believe we’re already there.

The Lost Generation That Never Got Lost

Beginning in the 1960s, researchers administered a survey to college students that measured something called the internal external locus of control. By making participants choose between statements like “What happens to me is my own doing,” or “Sometimes I feel that I don’t have enough control over the direction my life is taking,” the test measures the degree to which one feels control over their life. Those who feel in control are said to experience an internal locus of control, while those who feel like life happens to them experience an external locus of control. The results tend to predict one’s susceptibility to anxiety and depression.

In the early years of the survey, most participants felt a sense of control or at least autonomy within their life, and only a small subset experienced the less desirable external locus of control. But by the 2000s, things had changed dramatically. In 2002, the average college student felt less control over their life than 80% of students in the1960s. For younger children, the change was even more dramatic.

During this same period, rates of anxiety, depression, and childhood suicide increased more than five fold, and they continue to rise. Between just 2007 and 2017, suicide rates for ages 10 to 24 increased by 56%, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Some psychologists believe that the changing nature of childhood, driven by the rise of intensive parenting and increased emphasis on academic achievement, is to blame.”

I am absolutely convinced that it’s because we have been gradually taking children’s freedom away,” Gray says. “This is the first time in the history of the world where children have been so micromanaged... There’s never been a time in the history of the world, and I’ve said this in front of anthropologists who would probably know, that children have been so unhappy.”

Cultivating Boredom for Better Kids

Parents who want their kids to thrive by killing time should take note: The success rests more on what parents don’t do.

“I want to help parents relax,” Mogel says. “I want [kids] to work. And I want them to play. And I want the parents to butt out.”

Mogel also emphasizes the importance of experiencing low-level disappointment as a kid. “We want them to experience the whole range of emotions and learn that emotions come and go, and what you can do to feel better,” she says. “That disappointment doesn’t kill you.”

Gray urges parents not to control the activities their kids choose when they’re bored, even when they’re online. He notes that parents tend to see screen time as a tragic vice that’s replaced the outdoor childhoods of decades past. But, he challenges parents, what if it was the other way around? What if, forbidden from playing in the streets or other parent-free places, kids have turned to the internet as one of the only spaces free from prying adult eyes?

“Children are already too constrained. If you take the online world away from children, then you have really taken away their opportunity to play and to interact with other kids,” Gray says.

That may sound cavalier, but Gray notes that children who don’t get any screen time are likely suffering more than those who do. He cites a 2016 study out of Columbia University of over 3,000 children ages 6- to 11-years-old that found children who spent more than five hours per week playing video games were actually doing better in school than those who played them less often.

Gray is even critical of research that links social media use to depression, pointing out that large sample sizes enable very small correlations to be statistically significant. So although there is some correlation, Gray says, 99.6% of depressive symptoms can be explained by factors other than social media use or screen time. That other 0.04%, Gray points out, leaves social media about as strongly linked to mental health as potato consumption.

Fathers and Free Play

Dads have a unique opportunity to provide the kind of free play that’s been proven to be so beneficial, Mogel says. After all, dads tend to let kids do riskier kinds of activities and provide more fun.

In a recent parenting class, Mogel asked the parents what their favorite memory with their dad was. She was surprised by how many of them brought up instances that involved water, like a day at the beach.

“These parents memories were so vivid, of adventurous times with dad, that were pretty carefree, free range, saturating the senses and some danger,” Mogel says. “And they were not fancy. Nobody said, oh, I remember our trip to Paris. None of them were about culture. They were all about nature. We’re depriving children of this.”

Mogel still points parents to the books of Louise Bates Ames, despite the fact that the descriptions of shopping 5-year-olds may seem outdated. True, it’s unlikely that the parents she works with will be sending their Kindergartner to the store any time soon, but maybe they’ll be willing to let go a little bit. Maybe they’ll let their children be children a bit more often — left to their own devices and building autonomy, resilience and creativity out of an afternoon of utter boredom.

This article was originally published on