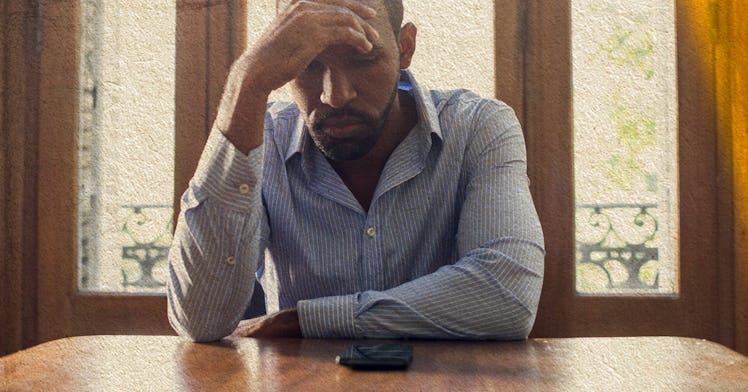

Political News Is Bad for People, Specifically Parents

In our modern media era where political news dominates, parents are affected in a particularly harmful way.

Every generation has the memory of a momentous or catastrophic event that played out on the news when they were children. The moon landing. The Kennedy assassination. The events of 9/11. The experience of seeing stories develop in real time on a mass scale makes them totemic events in the lives of children. It also makes them totemic events in the lives of parents who must navigate their own fears while helping their children understand and process what flashes before them on screen. In our modern media era where political news dominates, adults and parents are affected in a particularly harmful way.

Plenty has been said about the benefits of shutting off the constant barrage of information and wheel-spinning that comes from the 24-hour news cycle. One of my favorite explanations came from author Yuval Noah Harari. In a conversation with GQ, he said “I rarely follow the kind of day-to-day news cycle. I tend to read long books about subjects that interest me. So instead of reading 100 short stories about the Chinese economy, I prefer to take one long book about the Chinese economy and read it from cover-to-cover.” It’s a practice Harari himself acknowledges leaves gaps in his understanding of the day’s headlines, but it ultimately gives him more calm and focus to specialize.

The negative effect of the news cycle on you and your family is twofold. First, you’re not actually getting the quality of information you’d expect from the quantity of news you’re consuming.

“Perhaps the biggest problem with the 24-hour news cycle is that few stories are given the depth of coverage needed for the audience to understand the significance of an event, the background behind the story, how the story fits into a historical context, and doesn’t provide an objective and balanced view of the different perspectives behind the story,” says Andrew Selepak, a professor in the department of telecommunication at the University of Florida. “While it seems counterintuitive, in our current 24-hour news cycle of cable networks and social media news, we now know less about what is going on in the world than ever before.”

But the more pressing problem this poses to childcare is in the developing mind of your child. Elesa Zehndorfer, author of the upcoming book Evolution, Charisma & Politics: Why Populists Win, notes that “the 24/7 news cycle is particularly vicious for youngsters as the immaturity of their (impulse controlling) prefrontal cortex… makes them especially vulnerable to tech overuse and addiction, stress, and anxiety.”

So, the news is not great for children. However, adults, particularly parents, are equally at risk for some of these downsides. Studies have found that both children and adults who are exposed to constant news and upsetting images can exhibit signs of PTSD from the overexposure.

“Becoming addicted to constant clickbait news headlines wears out dopamine receptor pathways,” says Zehndorfer, who adds that it “overexposes us to the stress hormone cortisol and poses a major danger to overall emotional health.” The influence of social media is particularly dangerous, Zehndorfer notes, due to the “roulette wheel” effect of not quite knowing the next image you’ll see, and yet feeling compelled to see what it is, no matter how disturbing or anxiety-provoking it might be. “The uncertainty ramps up cortisol and often the brain processes that image as if it is actually happening before it,” says Zehndorfer.

These addictive qualities may partially be due to the ‘natural negativity bias’ that leads our brain to pay more attention to threatening stimuli in order to keep itself safe. But in effect, adults may find that consuming large amounts of news as a way to stay informed will see them less able to distinguish between elements of the news and elements of their own lives.

“Viewing negative news means that you’re likely to see your own personal worries as more threatening and severe,” psychologist Dr. Graham Davey told the Huffington Post. “And when you do start worrying about them, you’re more likely to find your worry difficult to control and more distressing than it would normally be.” Distressing images will register in our brains as actual threatening stimuli, as Zehndorfer says, even though we intellectually understand them to be simply a visual representation. Stress, anxiety, and depression can quickly follow, along with their requisite physical manifestations. For people who are already stressed about the futures of their kids, this does no one any good.

It’s worth noting that there’s a separate psychological reality that inextricably ties the news’ effect on you to its effect on your child. Dr. Jennifer L. Hudson of Macquarie University cites bodies of research that demonstrate how parents model anxiety for their children.

“The degree to which a parent behaves in an anxious manner by either showing fearful or avoidant behaviors or by communicating threat to the child has been shown empirically, in a number of experimental studies, to impact on subsequent child emotion and behavior,” she says.

The result is somewhat of a feedback loop. You care about your kids and want them to be both informed and safe. However, as your perception of the news becomes clouded, you may find it harder to accurately communicate the state of things to your child, and may find you have trouble answering those difficult questions kids will ask about the world, which can’t help but add to the existing stress of parenting and your honest desire to parent well.

What’s more, the process of parenting requires a healthy amount of long-term planning, and while grim, fatalistic news throws everyone into a bit of an existential mess when they consider what their futures might bring, parents know that they’re not the only ones they’re responsible for. The stress of considering all sides of this can understandably make it hard to plan the contents of that day’s lunchbox, not to mention college, etc. You want to have all the answers for your kids, and you want to base your parenting around your confidence in the answers you have. The state of the 24-hour news cycle is bound to undermine that instinct, and make your job as a parent twice as difficult.

So what’s to be done here? I certainly don’t mean to pig-pile on the bad news, suggesting that just because the forces that govern our reaction to the news are stronger and more complicated than one would assume, it’s a necessarily hopeless situation.

However, there are plenty of ways to remove yourself and your children from the influence of the 24-hour news cycle. It’s just a matter, per the experts, of leaning away from a powerful contemporary current. And the answers are likely exactly what you think.

“Switch off social media,” suggests Zehndorfer. “Then identify a news source that has a bit of a filter — a high-quality newspaper that you carve out time to enjoy with a coffee, for example, slowing down and upping the quality of the news experience.”

Selepak concurs, also stressing, again, the importance in upping the reliability of the news-source you’re using, staying away from those who use conjecture and loose-ends to keep you tuning in.

“We have a choice and can decide if we wish to be informed or not,” he says. “But we can only do so when we go beyond the 24-hour news networks and seek out the news by real journalists who understand the awesome responsibility of their position.”

Reputable journalism gains nothing by stressing you out, and will necessarily avoid the sensationalism that will get a child hooked on something they don’t understand. You can’t solve all the world’s many problems for your child, but you can create an environment for your entire family — yourself included — that puts everyone back in the driver’s seat when it comes to how the news affects our emotions, and how it affects your ability to be a family in turn.

This article was originally published on