We Need Fewer Children’s Books That Teach Kids to Rebel For No Reason

Many children's books teach youth to ignore authority figures. But when toddlers buck the system because no one is looking, the results can be devastating.

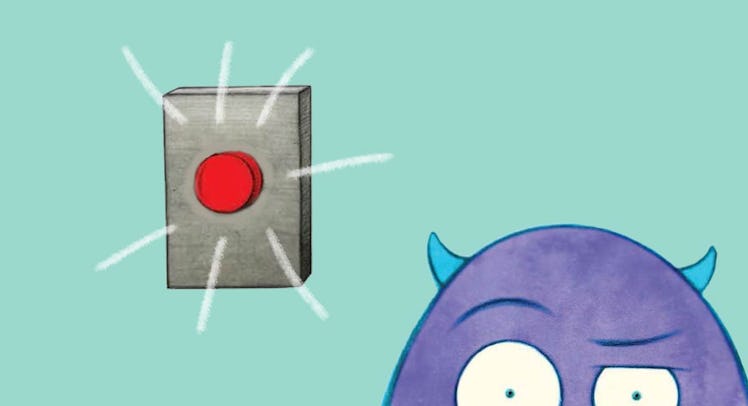

My 2-year-old sits on my lap, eagerly pushing a picture of a red button. The button appears on every page of the children’s book Don’t Push The Button, a story about a purple monster named Larry that goads kids into pushing a button that they’re not supposed to push. Larry opens with a cautious preamble (“There is only one rule. DON’T push the button”; “No! We can’t! We mustn’t!”), but then he levels with his juvenile readers. “Psst! No one is looking. You should give the button one little push.”

My child always complies.

Hijinks ensue. As children flip through the pages they discover that pushing the button turns Larry different colors, covers him in polka dots, and splits him into thousands of silly Larrys. At the end of the book, a key lesson is learned. When an adult says that there’s a dangerous button that you shouldn’t press, you can press it — as long as no one is looking, and Larry promises not to tattle.

Many children’s books teach youth to ignore authority figures, protest unfair treatment, and test boundaries—classic American stuff. And I get why parents want these books. We want our kids to become the sort of people who go on strike rather than work without blankets (Click-Clack Moo) or transcend gender roles (Good Night Stories For Rebel Girls). But when toddlers buck the system and break the rules because “no one is looking” or because adults are lame, the results can be devastating. If my 2-year-old presses an electrical outlet (“We mustn’t!”), the result will not be colorful Larrys.

Don’t Push The Button is not the first subversive children’s volume to essentially teach kids that it can be fun to trust strangers and ignore your parents. In The Cat in the Hat, the desperate pleas of a fish, who maintains that strangers “should not be here when your mother is out”, fall on deaf ears as The Cat promises to show the kids “a lot of good tricks” and assures them that their mother will not mind. If You Give A Moose A Muffin consists almost entirely of a child and a moose dodging the parents (the kid is in too deep; he gave a moose a muffin and now he’s on the hook for some jam and a puppet show). There’s a theme here, and it’s not one that I want my 2-year-old to internalize.

I’m not advocating a submissive reading list. Hundreds of studies have found that the authoritarian parenting style, in which parents enforce strict rules and punishments for disobedience, is an ineffective way to raise children. And there’s real value to reading books that teach children that authority figures are fallible. The labor leader in me certainly puts Click Clack Moo on a pedestal.

But how are we supposed to keep our children safe if every hero they encounter throws caution to the wind, ignores his or her parents, and pushes buttons that shouldn’t be pushed? Taken to an extreme, I wonder how many children run into the street to chase a ball, or act out in school, or try drugs and alcohol, because they’ve been taught that subversion is rewarded. To an even greater extreme, how many adults who groom children employ similar strategies to The Cat in the Hat— guaranteeing children that it’s OK because no one is watching, or that their mothers will never find out?

One way to strike this balance is to teach our children how to engage in meaningful rebellion. There is no value to pressing a button just because there’s a rule against pressing it. It also wouldn’t hurt to use these books as ways of pointing out the fallacies of tired tropes and poor decision-making by the main characters. We can point to the clueless parents in many of these volumes, and remind our children that not every parent is clueless — to the contrary, most parents know what they’re doing. We can read The Cat in the Hat, but remind our children that when a stranger walks into your house and trashes the place, keeping it a secret is a terrible idea. “Sally and I did not know what to say,” the Dr. Seuss classic concludes. “Should we tell her the things that went on there that day? Should we tell her about it? Now, what SHOULD we do? Well, What would YOU do if your mother asked YOU?”

I’d tell her. And I wouldn’t push the button. Maybe that’s the message my 2-year-old needs to hear.

This article was originally published on