How Many Kids Should I Have?: The Morality of Having a Larger Family

As talks of climate change and overpopulation loom, it's a question popping up more and more frequently. So, we asked four experts in various fields to weigh in.

In the 1970s, big families were commonplace. It wasn’t a surprise to see a couple with four children spread throughout various grades in school. The trend made sense: In the decade before, the national average birth rate per family was 3.65. Today, however, a family of four, or five, while not a shock by any means, certainly stands out. This also makes sense: In 2016, the birthrate was 1.8.

That number has been pretty locked in since 1990, and it’s created the American standard two-kid family. While it’s seen as a replacement rate – children merely replenishing the spots of their parents – for some, it’s still too high. Estimates have the current worldwide population of 7.6 billion growing to 9.7 billion by 2050, and 11.2 in 2100, possibly even 16.6.

Children, of course, add to a society. But they also create footprints and use finite resources. So the question arises: if you have control over your choices, is it ethical to have a large family? The topic is obviously complex, concerning competing values, the idea of individual choice versus the overall good of society, and many more ideas. To unpack the issues in this question, and to get a variety of opinions, we posed it to experts in four fields — climate science, bioethics, economics, and parenting. Here’s what they said concerning the considerations and impacts that come with having a family that’s larger than average.

Expert #1: Kimberly Nicholas, associate professor of sustainability science at Lund University in Sweden

Having a child is a huge decision in every way, and our research shows it has the biggest impact on the climate of all our personal decisions. We’re already very close to the limit for what the atmosphere can safely handle for carbon pollution.

My work looks at how we can cut emissions in half, starting with those of us with high emissions. We should be more ambitious in the United States because it’s about five percent of the world’s population and responsible for 25 percent of the greenhouse gases in the atmosphere.

But family planning is a human right and people have a right to make that decision. For me, the goal is to maximize, meaning, minimize carbon. Meaning, people have to decide for themselves what matters most, but we know plenty of ways to reduce carbon.

In our study, we found four substantial climate choices. Having one less child is the biggest, but living meat-, car-, and airplane flight-free are consistently high-impact. For example, in the U.S., most car trips are short: 60 percent are shorter than six miles. We can look at walking or biking when it’s possible. Are many overseas flights a year necessary? Probably not. For high emissions individuals, it’s important to dramatically reduce our emissions. We have options to make healthier and better choices for the environment while maintaining or increasing our quality of life.

Expert #2: Travis N. Rieder, research scholar at Johns Hopkins Berman School of Bioethics

There’s no amount of data that will spit out an answer, because different people have different contexts and values. A main factor is freedom of choice, such as access to family planning and the ability to have the number of children that an individual wants. It makes no sense to say it’s immoral if that person doesn’t have control over their choices.

But if they do, we can have a different conversation. The reality is kids are environmentally expensive. The planet can’t support an infinitely growing population. We should know that and that should help us do moral deliberation, but it still doesn’t make it easy. We can tell people to not eat beef because it’s environmentally insensitive, which is way less intimate and invasive than telling people to not have children.

Also, big families have particular value to some people. So there’s a tension, but another consideration I’d say is adoption. The children already exist. You’re not exposing anyone new to the risks of the world. You’re not creating new costs, and you’re providing a family to them. People often see adoption as a backup option for forming a family, but it doesn’t have to be that way.

But there is no simple answer and we shouldn’t act like there is. People should be aware of the stakes and costs, but we should be sensitive and respectful in the way we raise the conversation.

Expert #3: Andrew Foster, professor of economics and director of Social Science Research Institute at Brown University

It all depends on context. In countries with a high fertility rate and limited resources, kids create a net burden on other families. But in the United States, there’s a positive external benefit of an estimated $200,000 per child, a primary component of that figure is having a favorable age distribution. You need to replenish the population and have people down the road at peak earning potential to support older generations.

But there is the negative side, like the resources being used up, more carbon emissions. And there’s the question of being able to support your family, of paying for college. Most people don’t have the money when they have kids, but that’s a lifecycle thing, since you’re not at the peak of your earning. There’s risk involved and individuals can’t perfectly predict the future, but you can guess.

But it goes back to the national average. It’s an average because most people stick to it, so if a few couples have four of five children, most will benefit from that. And if couples are looking at having more, they hopefully understand that having kids is hard and expensive. If it’s something they value and choose, that’s perfectly appropriate.

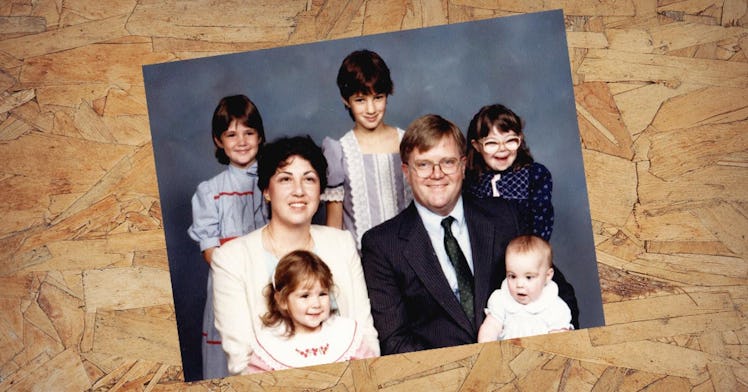

Expert #4: Eileen Kennedy-Moore, licensed psychologist in Princeton, NJ, author of Growing Friendships: A Kids’ Guide to Making and Keeping Friends, mother of four:

There are lots of reasons not to have a big family: money, mess, difficulty finding a babysitter, population concerns. Having four kids over a period of nine years means my husband and I will face 12 consecutive years of college bills. There’s really only one good reason to have that many: Falling in love with a child and watching that baby become a unique and separate person is unlike any other experience.

Children in big families might get less individual attention from parents, although I’m not sure that’s always true. You can have one child and ignore them. From my personal and professional experience, I know that kids don’t want us staring at them 100 percent of the time. What they want is for us to be responsive. When they need us, we turn towards them more often than away.

There are a lot of advantages from being part of a bunch. Kids learn about arguing and making up, negotiating and compromising, giving in and defending their turf. It’s good that they know that they’re not always the center of the universe, that they have to consider other people’s needs and sometimes someone else’s needs come first. It also gives them freedom to figure what they want and who they are. There’s less pressure to meet parents’ expectations because it’s not all on them. And, odds are, at any given point, they’ll be getting along with at least one sibling, and they often have a lot of fun all together.

As a parent, I figured out that I can’t do everything perfectly, so I had to focus. My kids became competent at an early age at dressing themselves, doing their hair, making their own lunches, and doing laundry. I limited the number of toys the kids could have out in order to keep the mess manageable, but I had loose standards for household tidiness. I just didn’t care and wanted to use that time to play with them.

I won’t say that having a big family is easy. It’s not, but it is deeply satisfying, and when you already have two kids, the incremental difficulty from having more is really infinity plus or minus one.