Migrant Detainment Centers Look Familiar to Survivors of Japanese Internment

As an expert in trauma, Ina is convinced that the trauma of her early life — not just in the camps, but in immigrant communities obsessed with modeling perfect behavior to an audience of Caucasian judges — affected the choices she made throughout her life.

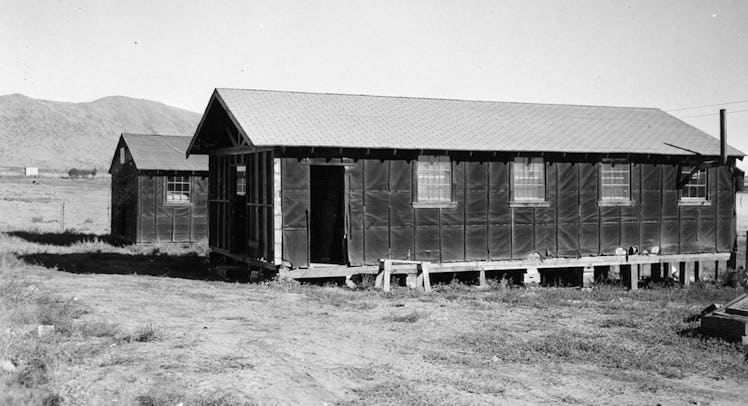

Satsuki Ina was not yet born when Emperor Hirohito ordered a bombing raid on Pearl Harbor and, in response, the U.S. government rounded up residents of Japanese extraction on the West Coast, bussing them to internment camps. She was born in one of those camps, a maximum security facility built at Tanforan Race Track, where her mother and father were living in a horse stable. Ina, now a 74-year-old psychotherapist and respected expert in child trauma, knows that the way she came into the world — under guard, under arrest, under lock and key — changed her life. Ina is convinced that the trauma of her early life — not just in the camps, but in immigrant communities obsessed with modeling perfect behavior to an audience of Caucasian judges — affected who she became by informing how she made choices.

This is why she recently snuck into a Texas detention center for Latin American migrants and why she is so concerned, not only about the Trump Administration’s former policy of separating families, but also about their current policy of detaining families together. Prison is prison. Armed guards are armed guards. Call the policy what you will, but internment is internment and imprisonment is imprisonment. Both as an expert and as a human being, Ina has been witness to this hard fact.

It’s also why she marched in Crystal City, Texas — the second such camp she spent her early life in — in March of 2019 with many of the remaining survivors of Japanese internment. In an email announcing the march, Ina said: “When we were disappearing from classrooms, jobs, neighborhoods, in 1942, there were no marches, protests, petitions to protest our unjust incarceration. Today, those of us who were incarcerated children speak up now to protest the criminalization of innocent children and families seeking asylum protection in the U.S.”

Could Ina already see the future? On June 11, 2019 the Trump administration announced plans to house the growing numbers of detained migrant children in Fort Sill, a military base that was also used as an internment camp for Japanese-Americans during World War II. Some 1,400 children will be moved there, without their parents, until they can be pawned off onto an adult relative. While the DHS says that the arrangement is temporary, calling the camp a “temporary emergency influx center,” they also already have 168 other facilities, and there are over 200 in operation in total. And the migrant population being apprehended at the border is surging: There’s been a more than 50 percent increase in children being apprehended since last year.

Although the Trump admin claims that these detainments are temporary, research shows that most detentions last from two to four years, and the administration has also rolled back programs that keep the camps constitutionally compliant like classes, sports, and other programs that keep the detainment centers from quite literally being a prison, which is illegal under the Flores Settlement. During the past 40 days, some 60,000 kids have been detained. Through all of the three years of Japanese internment in America, 120,000 people were placed in camps.

In this interview, which originally took place in June of 2018, Ina spoke to Fatherly about the beginning of her life, the legacy of trauma for Japanese-Americans, and what she’s seen at detainment centers, some of which she’s been to several times.

Given your experience in internment — and your parents’ experience of trying to raise you and your brother through that internment — visiting Dilley and Karnes [detainment centers for Latin American immigrants in Texas] must have been difficult.

The whole repetition of children being separated from their parents, being incarcerated for indefinite detention, it brought back, in three-dimensional life, images of what it must have been like for my parents.

And what was your role in visiting those centers? Why did you willingly go back?

The prison administrators were trying to get the prisons qualified as child development centers. We went to the board to testify and said: “This is a prison. No matter how many coats of paint you put on it, this is unhealthy for children.”

You were born in the Tulelake Segregation Center, which was a maximum security prison camp. You’re an American. You’re in your 70s. Does that still affect how you think about yourself?

I always think of myself being born as a prisoner; in a high-security prison camp, surrounded by armed soldiers and barbed wire fences. The living conditions there were very punitive and harsh. I was born into a traumatic environment. I was in utero during a very, traumatic uncertain time. My mom had very poor nutrition. She gave birth at a site where they didn’t have proper medical facilities and had a difficult birth.

I asked my mother why she would consider having another baby in a prison camp. She said they had very little information about their fate. They believed that if they had more children, they were less likely to be separated. Still, my father was taken away from us when I was a year old.

Why was he taken away from you?

My parents renounced their American citizenship. They had a crisis of faith in their own country. Once they renounced, it made them enemy aliens, a legal term that made it possible to remove my father and incarcerate him in a Department of Justice internment camp. My father was charged with sedition. He never got formally prosecuted for that, but he was removed and detained in an internment camp in North Dakota.

What do you remember of the internment camps?

My earliest childhood memory is actually of leaving camp. My parents were given 25 dollars each and a train ticket to Cincinnati, Ohio. I remember being on the train, and reaching across the aisles to swing back and forth.

Do you feel you experienced some unresolved trauma for the beginning of your life and childhood?

Certainly. I think it’s manageable, though, because I’m so aware of it. I’m constantly evaluating myself. My drive to be successful, there is anxiety underneath that. The outcome of that anxiety has become writing books, running a private practice, mentoring psychology students. Underneath all of that is the continued theme of having to prove that the injustice happened.

And I know that you’ve been very active in Texas, visiting Dilley, where there is a detention center.

A young ACLU attorney called me. He said: “These children are being detained with their mothers, seeking asylum at the border, and we’d like you to come to Texas and evaluate the level of trauma these children are experiencing.” It had to be done covertly. They don’t allow professionals into those prisons. But they do allow religious groups to come in as friends, to visit with the prisoners. I joined a church group. I went about three or four times.

What I saw was very disturbing: armed guards, pregnant women, nursing mothers, infants, toddlers. We were allowed to go into the visiting room, which is a large area with tables and chairs. The women and the children were pressed against the glass, hoping that they would get to come in and talk. One child I interviewed would check for a guard before she answered any questions. These children were having nightmares, regressing cognitively, wetting their pants even though they hadn’t been incontinent for years. And mothers were desperate with anxiety, not knowing how long they were going to be there until they could get access to an immigration judge who could determine whether they qualify for asylum. They had little contact with the outside world.

That has a lot of parallels to what you went through.

It’s happening again.

Are you surprised at all that this is happening again?

I wouldn’t say I feel surprised. I am alarmed. I asked one mother what made her decide to risk bringing her children through Central America and Mexico to Texas.

She said she had a daughter and a son. The son was separated and put in a male detention prison. The little girl was with her. Her husband had been shot and killed. The gangs came to her house to collect money. When she resisted, they told her they would take her son and make him a child soldier and take her daughter and put her into the sex trafficking business. She had been beaten. That next day, she collected her money and left. And she used that money to get a coyote to help her cross the border.

She was told by the coyote that when she sees the man with the border patrol hat, to put her arms up and say “asylum.” In the past, in the early Obama administration, asylum seekers were moved in with families so that they could show up for their hearings. But now that they’re characterized as criminals, they’re treated as criminals. They’re thrown into a cement holding facility with no beds in them. They sleep on the floor in an ice-cold cell, and they are picked up in trucks and transported to the detention facilities. These are prisons. With security gates.

And those prisons hold people who have not necessarily committed any crimes. Just like you and your parents and your brother were held, indefinitely.

That young attorney that contacted me — I asked him what he found most disturbing. The ACLU had a chance to visit before they started taking prisoners in. They showed him this room that had rows and rows of little shoes. That’s where he broke down. They were anticipating children.

Did you ever talk to your parents about internment? About what they went through?

My dad never talked about it. My mom would answer questions sometimes. I understand now that they were suffering from PTSD. That they compartmentalized everything that was painful. There was also the pressure after camp to constantly prove that we were deserving of being in America. The renunciation of citizenship had been deemed “decided under duress.” My parents got their citizenship back in 1957, but they were aliens until that point. So in the earliest years of my life, my parents lived in dread and fear because they didn’t have citizenship. They never bought a home. They were very concerned about us breaking any laws or being troublemakers or causing any problems at school.

The most important thing for us as children was that we had to do well at school and not cause any trouble. That was the main message that we got.

In other words — you had to appeal to white Americans by being “model citizens.” You had to work twice as hard. You had to be the most American. In what ways did that affect you?

My parents explained to me that when we started elementary school, my teachers told my parent, “If you want your children to be real Americans, they should have real American names.” Teachers named me Sandy. I was born as Satsuki. My brother, Kyoshi, was named Kenny. My father was a poet. He gave a lot of thought to our names. But out of fear, and the necessity to blend in to the American mainstream, they went along with it.

So you did reclaim your name. You go by Satsuki today.

Even when I told my mother I wanted to reclaim my name, she said, “Don’t do it. Bad things will happen to you.” It made me realize how she lived during those decades, with that fear that if we spoke up or claimed our identities overtly, we would be punished. She called me Sandy until the day she died. She just couldn’t take the chance of calling me by my real name.

This article was originally published on