The Supreme Court Defines (and Redefines) the American Family

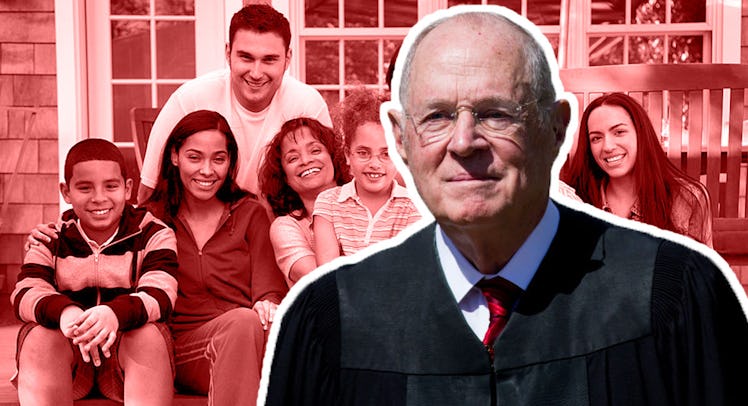

As Justice Kennedy retires from the Supreme Court, a swing to the right will change the future of the American family.

Supreme Court Justice Anthony “Swing Vote” Kennedy announced his retirement Wednesday to the elation of the political right and the horror of the left. There’s a reason both sides see the justice’s departure as such a big deal: President Trump now has the opportunity to appoint an ideologically conservative judge whose decisions could and likely will affect law for generations. And not only will the jurist to be named later change the course of legal history, he or she is likely to change the way American families look and behave. The Supremes have been doing so for roughly a half-century.

Prior to the 1960s, the Supreme Court stayed fairly clear of family life — affecting Americans through the rejection or acceptance of policies rather than through more or less direct decision making. That changed in 1967, the year of Loving vs. Virginia. The Lovings, an interracial couple who’d been prosecuted under Virginia’s bracingly racist 1924 Racial Integrity Act of 1924, challenged the right of their state to pass anti-miscegenation laws. The court ruled in favor of the Lovings and opened the door for the formation of mixed race families. Today, some 16 percent of American marriages feature partners of different races. At the time of the ruling, that number was just .4 percent. Sure, the change was driven by culture as well, but it’s hard to overstate the degree to which culture was directed or redirected by law.

A full 48 years later, in 2015, the Loving decision was cited as precedent in Obergefell v. Hodges wherein the court ruled in favor of gay marriage. This decision again allowed for a change in the way American families look. The court found that gay couples have the same rights of marriage as their heterosexual peers, allowing for health insurance coverage, right to property, hospital visitation, and equitable taxation.

Parental rights over their children were codified in the 1975 decision of Wisconsin v. Yoder. In this case, the justices found that Amish parents had a constitutional right to school their children outside the public education system. The case has been widely referenced as upholding a parent’s right to homeschool a child and guide their religious education without state interference. It is as popular on the right as Obergefell v. Hodges is on the left.

Another landmark case in 1965 likely affected the size of the American family by making it easier for married couples to learn about and receive contraceptives. The court’s 7 to 2 decision in Griswold v. Connecticut found a state law regarding the prohibition of receiving contraception to prevent pregnancy unconstitutional. This led the way to court rulings in favor of allowing contraception for unmarried couples and teens, as well as the right to homosexual relations in 2003.

But the Griswold decision was part of a rolling series of rulings that began with the decision that has been hashed and rehashed most aggressively by partisan politicians: Roe vs. Wade. Much like the Griswold decision and the Loving decision afterward, the court looked to the 5th and 14th amendments which, combined, create a legal and civil understanding of due process. Generally, the courts have long found that states cannot arbitrarily deny liberty to citizens without due process of the law. That was largely to focus on the ruling in Roe, not abortion itself.

But one might wonder how Roe did anything to shape American families. After all, wouldn’t making abortion legal specifically work against the creation of families? Well, no. Recent data shows that women who seek abortions are not, in fact, all young, single party girls terminating a pregnancy on a lark as some conservatives have seemed to imply. In fact, 60 percent of women seeking abortions are mothers 25 and older. Often, the reason they seek abortions is that they face economic insecurity and worry about their ability to provide for multiple children.

All of which suggests that the future of the American family will be highly dependant on which way the Supreme Court tilts on its increasingly shaky and politicized fulcrum. While it would be nice to assume that over 50 years of precedent would lead to judges ruling consistently on future cases regarding family planning, marriage rights, and even education, that is not a given. Some of the nominees on Trump’s already released list are vocal opponents of gay marriage, among other things.

It seems increasingly likely, barring a successful bid by Democrats to block an appointee, that President Trump will appoint a conservative ideologue to the high court. And it is likely that the court will, sometime after that, limit access to abortion and provide states with an opening to discriminate against, at a minimum, gay families. It is also likely that, at the same time, the politicians that vote for the new judge will continue to hack away at the social safety net, putting many parents in an economic position that will force them to consider or reconsider family planning. It remains unclear in what ways a conservative court will see fit to allow them to do this.

This article was originally published on