Why Jewish Families Fight Like Jewish Families

The percussive din of a Jewish family dinner is legendary. Here's how it happened, and what it says about Jewish culture.

The percussive din of a Jewish family dinner is legendary. Tell my Jewish mother that you’ve had enough chicken soup, and she’ll ask what’s wrong with her recipe. Plead satiety, and you’ll be declared unwell. (Such chutzpa to show up at the table with a cold. You’ll infect the family).

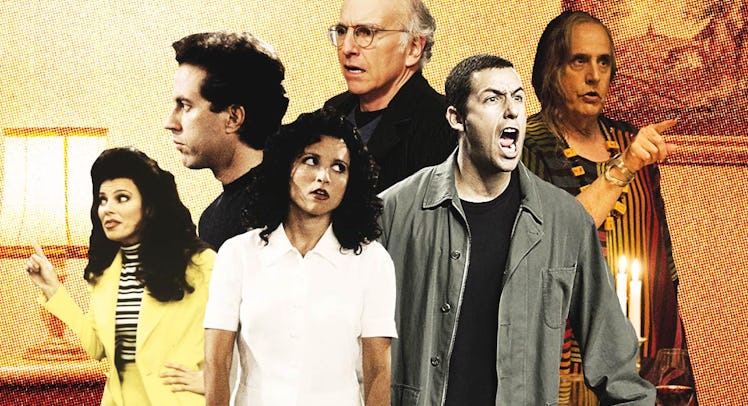

My people, from assimilated Americans to frocked Hasidim, have no concept of what it means to sit and eat in silence. Yiddish, the pidgin language of European Jewry, contains twice as many words for “argue” as “happy.” WASPs nibble overcooked steaks to a soundtrack of tinging silverware; we debate dinner with our mouths full. There’s a unique cadence to the Jewish argument, captured by Arthur Miller, Larry David, and countless pretenders. An undercurrent of faux offense and guilt, sporadic bouts of deference. Voices are raised and, twenty minutes later, it never happened.

But why do Jewish families argue like Jewish families? And what can dinner debates teach us about how culture shapes the way that families fight? Experts suspect that Judaism’s long history of incisive argument and religious persecution helped shape a unique brand of altercation—the neverending verbal slapfight.

“Arguing is not hostility, in the Jewish culture,” Barry A. Kosmin, a sociologist at Trinity College who studies contemporary Jewry. “There’s a long history of religious disputation that has carried into the contemporary period—passed down through family, and over the table.”

The Jewish people are not alone in their penchant for a loud argument. Italian families have been accused of fighting in the same manner and at a similar volume. The similarities, Kosmin ventures, may be a result of both peoples’ Mediterranean roots — or the fact that both societies have been mired in political upheaval for millennia. “Among the Jews, there has always been the religious versus the non-religious. In Italy, there were very strong Catholics, communists, anarchists,” he says. “In societies with a lot of political differences, one can agree to disagree and still be friends. One can say, ‘You’re a nice person, even though you’re an idiot when it comes to economics.’”

Kosmin cites the Israeli Knesset, which is known for shouting matches that make British Parliament sessions look like a tea party. The disagreements are real, but the vigorous style of debate is mostly theater. After an evening of gesticulating and shouting, Knesset members often retire to a group dinner. Kosmin compares this behavior with the vigorous Supreme Court arguments between lifelong friends Antonin Scalia and Ruth Bader Ginsburg. “These are people who disagreed over a meaty issue, and then went to the opera together,” Kosmin says. “That’s a very non-Northern European way of operating.”

Indeed, studies have shown that communication style is influenced by culture and region. Sociologists split cultures into “high context” (communication through nonverbal cues and between-the-lines interpretation) and “low context” (explicit, frank conversation). Slavic, Central European, Latin American, African, Arab, Asian, American-Indian, and Mediterranean cultures are considered “high context”; Germanic and English-speaking countries, “low context.” These differences extend to emotional expression, too. One study found that Italian, French, American, and Singaporean cultures broadly accepted emotional outbursts in the workplace. In Japan, Indonesia, the U.K., Norway, and the Netherlands, emotions are given no quarter in the boardroom.

If the Jewish people are indeed products of the Mediterranean, one would expect a high context culture—shrugging, passive aggression, the body language of a Bubbe—and regular emotional outbursts. If you don’t eat your soup, then you don’t love me! The sociology, at least, checks out.

But Jews and Italians have very different histories. The Jewish people have existed outside of the Mediterranean for thousands of years. So Kosmin suggests a second cultural influence on argument, one that crosses national borders—shared literature. The Jewish intellectual tradition is rife with debate. Biblical characters argue with one another and, on occasion, with God Himself. The Talmud, perhaps the most-studied of the ancient Jewish tracts, is effectively a transcript of study hall debates. “The Jews in Yemen and the Jews in Poland were all reading the same Talmud,” Kosmin points out.

Thus the theory: Jewish families argue like Jewish families because of their regional roots and historical embrasure of debate. Unfortunately, these notions are mostly anecdotal—and primary sources may call them into question. “I don’t have some ready source of ethnographic or sociological data that proves that Jews really do have a specific brand of family fighting, much less any solid comparative or historical data about where it started, how far it reaches, whether it is specifically related to class or religious observance,” Kenneth B. Moss, a professor of Jewish history at Johns Hopkins University, says. “When one reads memoir literature and other such slice-of-life materials, it becomes clear that any broad generalizations must be wrong.”

Moss raises the possibility that the Jewish style of argument did not really come into its own until the early 1900’s, as a product of Enlightenment-based youth rebellion, alongside vast waves of immigration to America that destabilized the European patriarchal family structure. “The classic trope or imagined site of Jewish argumentativeness in Eastern Europe is less the dinner table than the study hall or the yeshiva, where interpretive argument of various sorts was a key part of Talmud study. But I don’t think it’s clear that there was a culture of argument in the home. I think things were pretty patriarchal until fairly late in the modern era,” Moss says. “It might be the case that, as part of the general transformation in attitudes about religion, politics, tradition, aspirations among many, though not all, Jews in Eastern Europe between 1880 and 1939, there emerged a new culture of family debate and argument.”

I, however, am a millennial. Whether Jewish family fighting originated four millennia ago with Abraham, or circa 1940 on American shores, the only world I have ever known is one of perpetual, friendly bickering. I grew up in a loving, slightly overbearing, and incredibly loud home. Children in my family learned to make their points succinctly. If my brother took too long to express his opinion, he found the conversation had already washed over him and moved on to something else. Our dinner table was a paradigm of the Socratic method (albeit at a decible that would surely have flustered Socrates). We did not quite realize that we were debating or arguing—nor did it register that the Talmud we studied in school was essentially a full book of arguments.

We figured this was how every family talked.

The first time I joined a protestant friend for dinner, and his brothers and sisters cut their meat in silent fellowship, I felt a chill. It was though someone in the family had died.

As American Jewry slowly assimilates, however, this standard may be changing. “American Jewish millennials have lost a lot of the cultural baggage from the past, some good, some bad,” Kosmin says.

Indeed, Jewish culture, if not religion, has long been a product of its local environment. As my people shift from Europe to the United States, it is inevitable that we act less and less like Europeans and more and more like Americans. At my grandfather’s Bar Mitzvah, they served herring. At mine, sushi. It follows that Jewish family fighting styles will evolve with the seafood. “It’ll change slowly,” Kosmin says. “I expect people in their 20’s and 30’s to have very different relationships with their parents.”

As for me? I intend to keep the traditional alive. My grandchildren will be expected to finish the soup and to call me once a week. There will be hell to pay, if they do not.