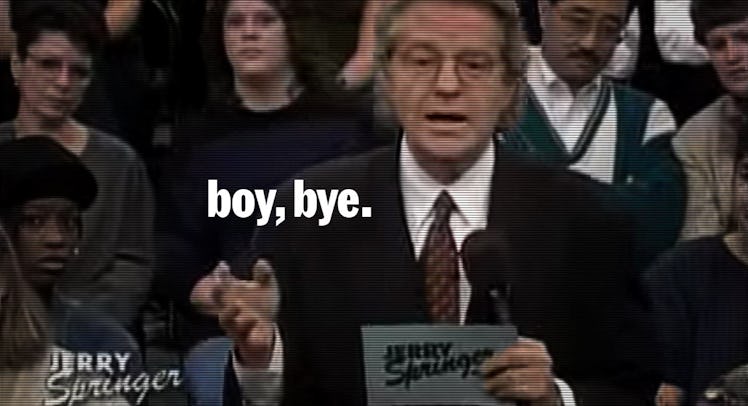

‘The Jerry Springer Show’ is Dead. Let’s Dig It Up and Kill it Again.

The Jerry Springer Show exploited family trauma and an audience's need to feel superior. But the cure to the dehumanization was empathy.

Producers confirmed this week that the Jerry Springer Show has been canceled after 27 seasons. That’s around 4,000 episodes featuring fistfights, strippers, affairs, affairs with strippers, homophobia, transphobia, white supremacists, and at least one dude who married a horse. The long-running show orbited around the idea that entertainment could be derived from watching poor or uneducated (preferably both) people express their feelings inarticulately. The in-studio audience’s jeering, laughter and chanting (Jerry! Jerry! Jerry!) was indicative of the ways in which guests were dehumanized on Springer’s stage. They were also critical to the show because the very second viewers saw one of Springer’s guests as a human worthy of empathy, the artifice crumbled and the show became sickening.

I watched Springer religiously in my early to mid-20’s during a period that might be considered the “golden age” of the show. This was back when chief security officer Steve Wilko was emerging as a reluctant celebrity for his role in breaking up the increasingly predictable fist fights. My job at the time allowed me to hole up with my housemates on lazy afternoons to smoke weed and watch afternoon TV. We would stare incredulously at the screen as a parade of affairs, incest, and surprise gender revelations destroyed relationships in front of our very eyes, grooving to the strains of guests’ inevitable backwoods twang.

There were plenty of surprised gasps on our couch. There was laughter. The term, “white trash” was used liberally. There would be an occasional debate about the outcome. And if we ever felt uncomfortable about watching Springer, we could pretend our voyeurism was an intellectual exercise by talking about the show’s role in informing popular culture.

But that’s not really why I was watching. The reason I felt so drawn to Springer was that I recognized the guests from the rural Colorado communities I grew up in. I recognized the feuds over lovers and parentage. I could picture with distinct clarity the crusty shag carpeting of their double wides. I could practically smell the stale cigarette smoke on cheap upholstery and hear the thin slam of aluminum screen doors.

Jerry’s guest came from a world I’d barely escaped. And from my place of remove in front of a grainy, low-definition, late-90s television screen, I could feel superior. I could laugh at the people who were still trapped. And if I felt anything for the guest and their plight, it was a weak, tongue-clucking pity. I reveled in the fact that I could now feel shocked and entertained by an exotic weirdness that had once been my reality.

The feeling bled into my personal life too. My friends and I, a cadre of hippy, intellectual elites would take ironic trips to the mall, in the small city down the road from our liberal college town. It was our own, personal, Jerry Springer show. We’d buy an Orange Julius and walk around the stores talking behind our hands about the crispy claw bangs, obesity, and children on leashes. We’d look down our noses at the excess while buying a new cartridge for the houses shared Nintendo 64. We’d sit on benches and laugh, practically daring the men in John Deere hats to come start something. They never did.

Then, one day in the mall food court, something changed.

I remember waiting for a friend who’d gone to the bathroom and staring with disdain at the mall cop standing beside the Panda Express. My thoughts were dark and mean. But then something in his face triggered a revelation. This man existed out of my line of sight. He’d been through stuff. He was going to go through more stuff. He had cried by himself. He had felt as alone as I ever had — and if he hadn’t, he someday would.

It was a strange moment in that there was no real precipitating event. Something in me shifted and I saw, for a second, past the false dichotomy at the core of my world view: Some people get it and most people don’t. I stopped speciating humans and started feeling like one. Tears came to my eyes and I felt ashamed of myself.

I staggered out of the mall that day dazed by the sun and the sudden rush of empathy to the head. I tried to watch The Jerry Springer Show again, but it had stopped being entertaining. When I watched, I no longer saw “trash.” I saw people whose lives were in legitimate turmoil, often through no fault of their own. I began to remember the pain of the poverty and how it ate at the people I knew growing up. Springer wasn’t amusing anymore; it was a formulaic nightmare.

Now, some twenty years later, I’m happy to hear the Jerry Springer Show is cancelled. Still, I’m keenly aware that its ethos isn’t. Us versus them has not, as a mentality, gone out of style and there are plenty of programs and politicians that bank on cynicism. My hope is that I can teach my boys to view others clearly and to be empathetic. My hope is that shows like the Springer Show will never hold any appeal for them. I’m not sure if that’s realistic — sometimes one just needs to put on some miles to get there — but it is something I think about.

Watching the poor and the uneducated duke it out in front of a live studio audience is not only a miserable way to spend time, it’s a lazy way to engage with a hypothetical. The Springer Show dared its viewers to ask, “What if I was like that?” Most dismissed the question. But the truth is that we’re all like that. We’re people. We do dumb stuff, we get desperate, we get prideful, and we embarrass ourselves. That’s not just a premise for a ratings monster, it’s life.

This article was originally published on