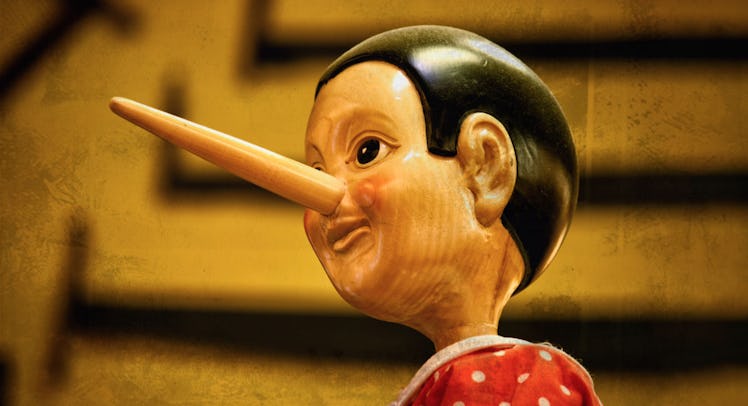

I Lie to My Kids. But Only About the Small Stuff

The big stuff we discuss as best we can.

As I make the turn into our neighborhood after picking my son up from preschool, he asks: the dreaded question: “Papa, can we watch Trolls tonight for our movie?”

Oh god, please no, I think. Please spare me. I can’t take another night of this awful movie. It’s already been 3 weeks in a row! I know how much he enjoys the movie, and he only gets to watch TV once per week, and it’s supposed to be his choice. But if I see those poofy-haired dolls sing about happiness one more time, I’ll lose it. So I do the only thing I can: I lie.

“Sorry, Griff, I looked earlier and someone has already checked out Trolls for tonight. We’ll have to choose something else to watch.”

I glance in the rear view mirror just in time to see a look of disappointment creep across his face. He doesn’t know that I lied. He doesn’t know that Blockbuster Video went out of business and no one rents movies this way anymore. But, really, what’s the harm? He still gets to watch a movie, we still get pizza and cuddles on the couch, and I save myself from the insipidness of the brightly coiffed dolls for one night. In my eyes, that’s a win-win. But it’s also a win based on a lie.

I recognize that how truthful I am as a parent often depends on how I think my kids will react to be me telling them the truth.. When I tell my son we can’t go to the playground because it’s “too hot,” I actually mean, “I’m tired and don’t have the energy to chase you around right now.”

I tell myself that using a lie to deny Griffin a privilege — TV, a treat, extra time at the park — doesn’t pose the same moral quandary as using a lie to “protect his innocence.” I use quotes here because I feel like adults tend to employ this idea of safeguarding the “delicate mental state” of young people as a way to avoid big conversations. And as parents, my partner and I try to make a distinction.

Sometimes, parents use lies of omission to avoid talking about uncomfortable subjects. I often wonder who the lies really protect. After all, it’s easier to tell our kids that the family dog has “moved to the country” than it is to teach them about death, and help them learn about grief, and what it’s like to lose a loved one. But these omissions make me wonder who the lies are really supposed to protect: us parents, or our kids?

Pretty early on, my partner and I decided to be honest and straightforward when it comes to the big stuff. We decided not to just tell the truth, but to offer up truth as fully as possible. Especially when it comes to the harsher realities of the world. Far from risking their innocence, we feel that being honest about substantive issues—gun violence, racism, death—is an investment in our kids’ emotional intelligence. We are in effect, telling them, “Yes, these truths can be scary, confusing, and sad, and we’ll be here to help you make sense of them as you learn to understand and deal with them.”

When a friend’s grandmother passed away recently, we stumbled into another opportunity for honesty with our Griffin. My wife told him, “Baba, I need to tell you something before we go to Tia Vivi’s. Tita won’t be there because she died last night.”

“Where is she?” he asked.

“She’s not here anymore,” my wife answered.

“But where did she go?”

“Well, she died, like my parents did. You know how my parents aren’t living anymore? How they’re not here?”

“But how did she get there? Did she go on an airplane?”

“What?”

“Did she go on airplane to be with your parents?”

So our honesty doesn’t guarantee our four-year-old’s understanding, as we discovered a few days later while playing on the playground. While Griffin is on the swing, a plane caught his eye. “Look!” he exclaims. “There’s Tita’s plane! Hi, Tita!”

Being honest also helps us counterbalance the privilege our kids enjoy, by letting them know that not everyone lives free of hunger, abuse, poverty, gun violence. Sometimes we have to work at this. We take our kids with us when we go to do volunteer work at soup kitchens or help at school clean-up days.

More recently, the shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in nearby Parkland, Florida, gave us the unwanted chance to remind our son that playing with guns, even pretend ones, even when they’re toilet-paper cores pressed into service as firearms, is not acceptable in our family.

“Griffin, we do not pretend to shoot anyone. Guns are not toys, and they are not to play with. Do you know what happens when people use real guns to shoot someone?”

“They get hurt, and they go to the hospital, and they could get dead and not be able to play or watch Octonauts anymore,” he answers.

“That’s right. And when you’re dead, you’re not able to do the things you like to do, or see your family anymore, and they can’t see you. How do you think that would feel?”

“Bad. Sad,” he replies. In a way, in even the smallest way, he gets it. And that’s what matters.

Just a couple weeks after Parkland, a father in our neighborhood accidentally sent his seven-year-old to school with a loaded handgun in his backpack. Our neighbor’s son attends the school and excitedly shared the news with us on our local playground that afternoon.

“Hey Nick, guess what happened at my school today,” he said, proud to be the bearer of breaking news. “Some kid brought a gun to school in his backpack.”

“Geez,” I lamented. Then Griffin loudly chimed in: “YOU’RE NOT SUPPOSED TO PLAY WITH GUNS, because guns can hurt you and make you dead, so that’s not funny, Jose.”

Point taken.

I realized in that moment that my son has heard me. He understand our concerns, and what we’ve told him. And with that understanding comes a confidence that encourages him to speak up for what he thinks is right.

Griffin might not understand what death really is. He doesn’t know the politics that surround gun control and Florida. But the more we talk to him about the “big stuff,” the more he understands. And hopefully, that will keep him safer than any big lie ever could. (We’re still not going to watch Trolls, though).

This article was originally published on