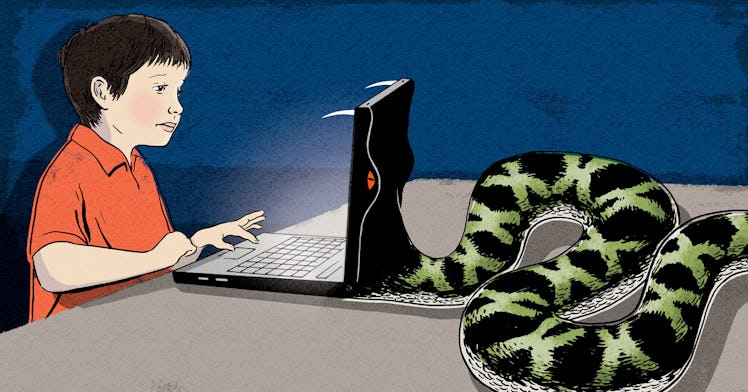

Helicopter Parenting Is the Only Way to Keep Kids Safe on the Internet

The dangers online for kids are very real. It’s time parents took a paranoid note from helicopter parenting and hovered over their kid’s screen time.

Helicopter parents have been a symbol of awful and overbearing child-rearing since they were first described in the late 1980s. But history might just vindicate the helicopter parent. Their anxiety and stranger danger panic isn’t unreasonable as much as it is misplaced. The fact is that when it comes to a child’s online safety, helicopter parenting should be the rule.

Helicopter parenting was always, in part, a reaction to the growing concern of child endangerment driven by an emerging 24-hour news cycle and high-profile child abduction cases. But the fear, while potent, was largely unfounded. There wasn’t actually a national child abduction crisis (less than 1 percent of missing children were non-family abductions). But there may very well be a national (if not global) online predator crisis.

According to a recent report from the Center for Cyber Safety and Education, 40 percent of kids in grades 4 through 8 connected or chatted with a stranger online. Of kids who met a stranger online over half gave them their phone number and 15 percent attempted to meet the stranger in person. The report is based on a relatively small sample size, but the results are shocking none-the-less. And there is data to suggest that the number are accurate.

“At any given moment of time, when a child goes online, there are 50,000 offenders attempting to have contact with children,” explains Camille Cooper, the vice president of Public Policy for the Rape, Abuse and Incest National Network (RAINN). “The scale of the problem is far greater online than it is in your backyard.”

Nevertheless, as children have increasingly moved indoors, parents have barely put up a fight against these new dangers. “Parents are hovering in the real world but they’re not even paying attention to what their kids are doing online,” Cooper says. “When you allow your kid to go online you’re giving the entire world access to your child. It’s a parent’s job to be vigilant.”

It’s critical to note that the 50,000 online predators are not simply hanging out in forbidden corners of the internet waiting for children to stumble into the wrong place at the wrong time. Rather, they are logging in to the apps, games, and online spaces where kids congregate. They exploit the social functionality of these spaces in order to make contact. And they do make contact.

40 percent of kids in grades 4 through 8 connected or chatted with a stranger online. More than half gave them their phone number and 15 percent attempted to meet the stranger in person.

This is why the danger is not in the access of the internet, but the way the internet enables communication. Chat features are built into almost every app, game and social platform to make the experience more communal, real, and immediate. These functions also allow kids to be contacted by virtually anyone. Even games that seem benign can be dangerous. According to NBC News, reporters were able to find at least 100 accounts linked to neo-Nazi extremism on the popular online multiplayer game Roblox.

Roblox is beloved by elementary school-aged kids and offers users the ability to interact with each through voice or chat features. Those same chat features can be found in popular online games for kids like Fortnite and Minecraft, and these features have been used by sexual predators to groom children — which means using coercion and manipulation to prepare and lure a child into a sexual encounter. In one high profile case, a man used Minecraft to groom two boys aged 12 and 14. And there have been reports of parents uncovering attempted grooming through Fortnite.

Even apps specifically designed for children are porous. Facebook recently came under fire when it was discovered that a bug in their chat app designed for children allowed thousands of kids to interact with unauthorized users.

When you combine the danger of children connecting with strangers with the addictive nature of online games and communication, the scale of the threat becomes truly overwhelming. And yet, many parents, either trusting parental control or their children’s judgment, allow kids to roam the online world with little concern.

According to a PEW Research poll related to online monitoring, 40 percent of parents did not check the website their teenagers were visiting. Another 40 percent did not check on their teens’ social media usage. Less than half of parents ever looked at their teen’s texts or phone records. Even more damning, only 39 percent of parents reported using parental controls to block, filter, or monitor their child’s online activity.

There’s a good likelihood that the lack of oversight might come from the backlash against helicopter parents (a backlash we’ve been a part of). Few parents want to be seen as overbearing and overprotective. After all, parents are told again and again that helicopter parents and their machine-parenting counterparts — the snowplow and lawnmower parents of the world — have practically ruined the upcoming generation of children. The children of helicopter parents are said to be depressed, stressed-out, and virtually incapable of doing anything themselves. But letting them do go online themselves is just not worth the risk.

As the director of K-through-12 safety for the educational and home internet monitoring platform Securly, Mike Jolly compares the lack of oversight to just tossing an inexperienced kid the keys to the car. “It’s like saying ‘Good luck!’ without ever driving with them or putting them through drivers’ education,” he says. “When parents let their kids have open access, they’re putting them at risk for cyberbullying, and seeing things that can be harmful to them.”

Jolly notes that parents should have a different set of parenting strategies for the online world versus the real world. A certain amount of trust and latitude can be great for kids outside, but that same consideration should not be translated to their digital lives.

You’re not going to give a shit if someone calls you a helicopter parent if your kid is in the state attorney’s office because they snuck out with a pedophile.

Research bears this idea out. When it comes to child development, kids require a certain amount of challenge, exploration, and risk as they grow. That’s how kids learn about their own bodies and the rules of the physical and social world they inhabit. Pediatricians and child psychologists recommend that parents allow children to fall, fail, and push the limits of their abilities. But only within safe boundaries. You’re not going to allow a toddler to learn to walk at the brim of the Grand Canyon, for instance.

A kid who has access to any part of the internet that directly contacts with anonymous groups — that is to say, much of it — is like a toddler at the brim of the Grand Canyon. One slip could spell disaster.

As supervisor of the Florida State Attorney’s Office of Sex Crimes and Child Abuse Unit, Stacey Honowitz has seen the consequences of parents who were lax in their online supervision. “You’re going to be in pretty bad shape when you come into my office and your kid has been a victim because you didn’t look online to see who they were associating with, who was sending them messages,” Honowitz says. “We’re talking about a very undercover, discreet, sexualized society.”

Honowitz stresses that parents need to have full access and oversight to their children’s online world. That might mean a daily phone review of app and messaging use at dinner time; it might mean waiting to give children access to smartphones until they are in their late teens; it might mean installing robust monitoring software to track a child’s online activity; it might even mean regular talks about online risks. And while that may feel like hovering, it is necessary.

Also, says Honowitz, parents need to take the initiative to continue learning about the constantly shifting ecosystem of apps, games, and websites that children use. She recommends NetSmartz.org as a good resource. Another is the Common Sense Media website.

“There’s nothing wrong with saying, ‘I feel stupid when it comes to computers,’ ” explains Honowitz. “You can learn about it.”

But the bottom line is that parents need to stop feeling as if they are overbearing or invading a child’s privacy by watching over their digital lives. They should own the helicopter label proudly.

“You better grow a thick skin and not worry about what another person thinks about you,” says Honowitz. “Being worried about your reputation will harm your kid. You’re not going to give a shit if someone calls you a helicopter parent if your kid is in the state attorney’s office because they snuck out with a pedophile. You better grow some balls and think about the safety of your child first before you worry about what your peers are going to call you.”

This article was originally published on