Fatherly Interview: Elizabeth Warren on Inequity and What Dads Need to Do

Fatherly sat down with Elizabeth Warren to talk about the problems parents face today and how dads can be a big part of the solution.

Senator Elizabeth Warren understands the gravity and depth of the damage done by the pandemic. Well before COVID-19 shuttered the doors of child care centers, schools, workplaces, and more, she was sounding the alarm on one harsh reality: the American government has left parents, and in particular moms, to fend for themselves.

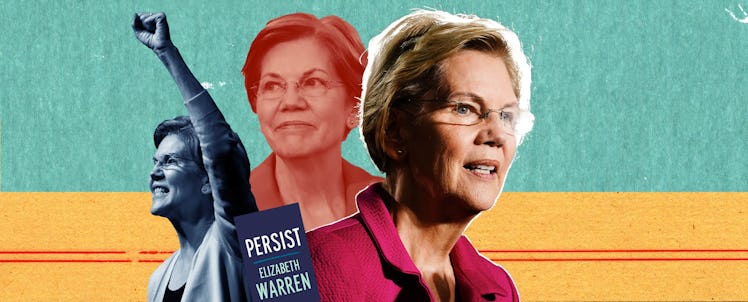

This is the reality of parenting in America. Child care is at times as expensive as tuition at a state college, parents are shut out of the housing market, pregnant people, like her, are discriminated against in the jobs market, educators constantly fight defunding, and giving birth can cost parents thousands of dollars out of pocket. These issues were all a large part of the focus of her 2020 campaign for president. Though she dropped out, the ideas she championed remained on the stage well after her exit. “I fought the childcare battles for years…,” she told Fatherly over video chat, referencing her own fight to get an education, to work, and to thrive while being a mom of two.Her ideas have only become more relevant, her reasoning more prescient. Which is why Senator Elizabeth Warren is so glad that her newest book, Persist, a book not just about the days, weeks, and months following her presidential run in 2020, and the career that led her up to it, but also about the crisis of unsupported parenting facing America, shown bare by the pandemic, is out today.

We talked to Senator Warren about her book, about her plans to “put more resources into housing,” and about why the government needs to work to “make investments together, to help create opportunity,” and what dads can do to be a bigger part of the solution to inequity. When I was reading your book, I was thinking about how you were writing about, before your Aunt Bee came along, how your childcare struggles were your own. You were dealing with it by yourself. You said you were a hair away from not being able to write those 12 books, get tenure, become Senator, run for president. Similar to that, what are dad’s roles in the fact that, prior to the pandemic, women weren’t supported enough, and during the pandemic support, any support system just crumbled? How can dads help?

EW: Dads could help by doing a lot more. We all eat. That means we all cook, and we all clean up afterward. One of the things I think, that’s really struck me, is the disconnect. In the book, I talk a little bit about the data — that dads help a lot more today than they did back when my children were babies. And we all nod and smile and say: that’s good! And they do. They help in lots of ways. Dads now, they’re at obstetrician appointments, and it’s not unusual to see a dad in the playgroup with little tiny ones. And that’s all wonderful. But one of the stats that came out of the pandemic that really knocked me over was who is managing the school-aged children’s schoolwork. And as I remember the numbers, 47 percent of the papas said, “y’all, I’m really doing it. I get a little help from time to time from the mom, but me, I’m taking it on.” Where, in that same survey — because they were asking dads and moms and, asking them independently — Moms said, “dads are doing this,” — are you ready? — “3 percent of the time.”Right.EW: Right? So there is clearly a disconnect. And to me, part of this is because of this notion that because it is her [the mom’s] responsibility, that if he is helping, he is the hero, right? And she’s just doing what she’s supposed to be doing. And I want to see if I can — I’m going to try to tie this in — this is the problem I think we’ve had in childcare all along. And why I talk about this with childcare. I have my babies, I love my babies, but I also wanted to be a teacher.

Getty/Corbis

I invested a lot in that. I wanted to finish my education, and then later, I wanted to hang onto this full-time teaching job. It was my problem to solve. It was, it was not my husband who, by the way, it’s not the current husband. It’s the first husband. When you have to number your husband’s, uh, it means something here. But that was my problem to solve.Right.EW: And we have all these male lawmakers, for generations, now. And I think they kind of treated it the same way. “It’s her problem to solve. And if she solves it, fine, and if she doesn’t well, that’s on her.” It so ignores how many women have to work, and how many women have to work for a whole lot of different reasons. Sometimes, you gotta work. Cause you gotta be the one who’s putting food on the table. You may be the only one there to put food on the table, but sometimes you’ve got to work because that’s your only chance to make it in your profession. You can’t take off six years or eight years or 10 years. If you do, you’ll never have the chance to be able to be all that you dreamed of when you were a little girl.

So I think your question about help at home is a little like the book Persist. It’s both very intimate, and household by household, family, by family. But at the same moment, it’s very national, right? It bleeds into the decisions we’re making as a matter of policy, and it’s why I am so hopeful at this moment that we are going to make change, that we are going to build universal childcare, that we are going to make that commitment. Right. My next question was going to be about what cultural changes need to happen — about how to make these rational, household by household decisions easier — but you just answered it. “Dads are heroes, and moms are just doing their jobs,” or, “A woman will figure it out, or she won’t, that’s about it.” That we reject that now — at least in theory — is a big cultural shift.EW: It is. Yeah, it is. And here’s another cultural shift, and it’s something I talk about in Persist: We need to use our voices. It is not enough for us to solve these problems on our own, because until we have public change, make policy change. The problems just keep recurring. I fought the childcare battles for years. I fought, and I cried, and I wept. There were times I had given up, I had just given up. I said, I can’t do this anymore. I just can’t. But my daughter faced the same thing. A generation later, childcare was no easier to get, by the time her babies were born than it had been when my babies were born. And here’s the thing that makes me grind my teeth. If we don’t make change, that problem is going to continue if my granddaughter has children. Right? So cultural change is, yeah. About the change at home. And no, you are not a hero for doing 47 percent of the work, any more than I am a hero for doing 53 percent — or 97 percent. But also I’m going to use some little part of who I am to get out there and fight for change, so this is not still a problem next year, and 10 years from now, and 20 years from now, and 40 years from now. This is a moment with a window, just a little bit, with the doors cracked, open. We got to run through it.Right. Speaking of policy, and policy solutions I read this line in the book, and my jaw dropped. “The single biggest predictor of going broke in America was to be a woman with a child.” What are the key policy solutions that help make having a family more affordable in the United States?EW: Childcare is a huge one, right? And as I say, that it’s universal, that it’s there and available. It’s not enough that it’s great five cities over, that on average it’s working, no. It’s gotta be near your home, affordable, available, and high quality. So that’s obviously a big part of it.Paid family leave is important — so that if you have to take time away from work. But understand it in a bigger context. The other thing that would make a big difference is housing. If we put more resources as a nation, into just strengthening our housing supply. This is across the board — for middle-class families, for working-class families, for the working poor, for the poor poor, for people with disabilities, for seniors, for everyone. In America, we used to be doing a lot of expanding housing. That changed.

I grew up in a two-bedroom, one-bath garage converted to hold my three brothers. Six of us, one bath, you do the math. That house, which was built by a developer, there were about 210 in our neighborhood plunked down on the Prairie in Oklahoma. That house is being built anymore. Private developers today are building McMansions and giant condos. And look, I’m not mad at them. It’s just the profit margins are higher, but it means the squeeze is on middle-class families on starter homes. And that’s true everywhere.LF: Right.EW: It’s not just a New York City, San Francisco, Boston problem. It’s true in rural America. It’s true in small-town America. That’s part one of the problem. Part two of the problem is that the federal government used to put a lot of money into building more housing units, housing units for working families, housing units for families that were struggling financially. And then in the late 1990s, they passed something called The Faircloth Amendment. And it said for every new federal unit that comes on the market, you have to take one off. So you don’t get any increase in housing supply. So I just want you to think that — the population in America has gone up over the last, uh, 30 years, right? And yet the two big sources of housing have basically either disappeared entirely or just been blocked. So housing deteriorates over time. Some of it, some of it ages, has to be taken offline, and it creates this real squeeze on families, on how much they have to pay. I mention this, because I just want to say all the pieces fit together, right? They’re connected. Childcare is connected to housing. We know the data on this. If you’ve got safe, affordable housing, if you have a chance to raise your children in good solid housing, they’ll have better educational outcomes. They’ll have better occupational outcomes. They’ll earn more money over their lives. There’ll be less likely to get into trouble. They’ll be healthier. You’ll actually just be healthier. And that’s how my point here, is that we need to do multiple things together, that are all driven by one central idea. What idea?EW: That is, we make investments together, to help create opportunity. And then you do with it what you do with it. Some people will do more with it. Some people will do less, but that we invest in opportunity, right? For all of our kids, we do that. We build a future, right? To that point, I was just thinking about a Stanford study I read the other day. That raising the minimum wage to $15 would lessen infant mortality significantly. It’s linked to all of these things. EW: Yeah. Yeah. Think of how those pieces fit together. Or, making the investment in childcare. Part of my plan on this is to raise the wages of childcare workers and preschool teachers in America. They are predominantly women, overwhelmingly women, and predominantly women of color who are working in childcare. And for many of them, they make more money if they go work at the cash register at McDonald’s. That’s just not right. And the thing is, it’s not like families can afford to pay more to childcare centers. In my view, [child care centers] are not paying low wages just because they’re mean people. They pay low wages because they’re trying to keep costs down for parents, right? Parents are already spending a huge chunk of their income on this. We don’t ask parents to pick up the full cost of sending a child to third grade. Why should we ask parents to pick up the full cost of all day long, early childhood education and childcare, and make that investment for all of us? We do. It’ll pay off many times.This year, obviously, all of us have been through a collective and also personal grief and sense of loss. You wrote about your own experience this past year in your book really beautifully. But your loss wasn’t just personal, and it was political. There was job loss, needless death, and then all of these structural failures. When you think of the future for working moms and dads, for American families, for the middle and working class, are you optimistic? EW: Yes, I am optimistic. I’m optimistic because we’re facing a climate crisis, but the Sunrise Movement is out there. I’m optimistic because we’re facing a childcare crisis, but millions of moms have had it up to here, and they’re letting the rest of the world know.I’m optimistic because people are getting crushed by student loan debt, but now they have organized to cancel the debt, and are pushing on Joe Biden to sign the piece of paper, to wipe out $50,000 in student loan debt. And Chuck Schumer, the majority leader in the United States Senate, is in this fight all the way. Those things tell me change is not guaranteed, but it is possible. We’re building the energy, we’re building the momentum, and we can do this. I started the book Persist the day after I dropped out of the presidential race. And it happened quite by accident. I was sad, and we live where there’s a sidewalk out front, and people have written notes on this sidewalk. “We love you.” Kids had drawn ponies and rainbows and, and the next morning I woke up, opened my door, and chalked down, in two-foot-high letters, heavily chalked in was the one word Persist.And I thought, that’s right. I got to the fight for the presidency, because of the things I wanted to fight for — the 81, juicy glorious detailed plans, because I saw how we could make this a better country. And I realized dropping out of the presidential race didn’t change that. I’m still in this fight. I persist because I believe that is how we will make change. I persist because persistence is personal. I persist because I’m just part of millions of women and men all across this country who are persisting and who are going to make it. This interview has been condensed, and edited, for clarity.