Family Time Is Overrated. Parents Need to Divide and Conquer

A family is always stronger together, right? Bullshit.

Right now I’m faced with a harsh truth that, day-by-day, hour-by-hour, minute-by-minute is becoming ever more clear: Family time is bullshit. Honestly, this is a line of thinking among experts — usually one put in less crude, more nuanced terms — that I’ve been following for a while. But, as it has done with so many things, COVID-19 has made spending time with family come to a head for me, and I can only assume it’s the same for millions of other parents locked at home struggling together.

The problems for any two-parent household are there in plain sight. Simply put, some of the more important lessons that a child learns from parents suffer when both parents are present. These include:

Discipline. Expressions of love.

Bonding.

Play.

The truth is, when your partner is there, it’s harder to discipline effectively, show love in a way that is meaningful, bond in a way that is believable, and play in a way that doesn’t lead to battles. The quarantine has shone a great bright spotlight on the fact that good child-rearing rests on one-on-one time. There are plenty of experts who are on board with the notion.

“You are often modifying your approach to discipline and behavior to integrate with your partner,” says Dr. Kyle D. Pruett, author of Partnership Parenting and a professor of child psychiatry at Yale University. “You might also defer to your partner on topics that your child might be more responsive to you, not them.”

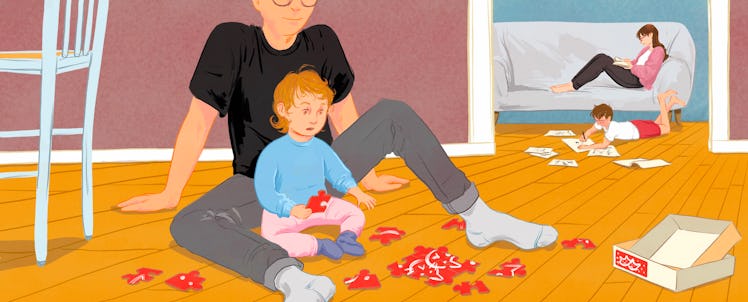

I’ve been experiencing this first-hand throughout the pandemic. Take the other day when, like most days, my family — my wife and I, a 2-year-old, and 8-year-old — was hard at work on a puzzle. My wife and I coordinated the piecing together (“let’s look for the duck butt”), and tried to make sure everyone had a task and was happy. At first, they were. The 2-year-old was naming animals, the 8-year-old was crushing the borders. We were pulling off some seemingly successful family time.

But then, the 8-year-old started helping the 2-year-old and it was heart-warming, except that she was doing all the work for him and he was starting to get restless. My wife and I tried to gently pull her away. He needs to learn on his own. You need to lead by example. ”I’m helping him!” she cried, and then she actually cried. We unsuccessfully tried to console her while also explaining what it meant to play with a 2-year-old. For her sake, we gave her the illusion of freedom and then yanked it back. For our sake, we prevented a toddler meltdown that was coming. To be fair, the situation was untenable from the start.

The problem here is the fact that there are two parents. As Pruett would point out, we’re “on a different trajectory” than our kids. “It’s a diad instead of a triangle — you need to play tennis with one instead of two.” Parenting is tough. Being a great partner is tough. Being a great partner and parent at the same time requires deft maneuvering that borders on impossible and quite frankly seems unnecessary. There’s an easy solution to all this: Hang out with your kid, on your own. They’ll love the attention, you’ll take the teeth out of the power dynamics between parent and child, and you’ll get through to them more easily.

When I am there in the very same situation just a few days later, sans mom, this plays out. My daughter puts together the piece for the toddler. “Let him do it on his own,” I say to her. “Dad, I did! But then he was, like, ‘I can’t do it,’ so I showed him how to do it.’”

No tears. No yelling. Just a rational, and rather articulate explanation of the situation. My 8-year-old was not threatened by a power dynamic — one parent’s world, in this household, is negotiable — and thus offered insight. I took it. Puzzle time was a blast.

There is a commonly-cited sociological principle of coalitions that helps shed light on what’s going on here. The textbook, Learning Group Leadership, a group dynamics book written for counselors, explains the idea of a coalition in a family as a set of groups that, to me, sound more like an explanation of tribal warfare than a happy family dynamic:

“In a family, this phenomenon might be readily observed as a father-mother subsystem; another between two of the three siblings; and another composed of the mother, her mother, and the third child. In a group, you might see this when there is a popular and powerful group—a couple members who have become close compared with those who are shy and not too confident. You can therefore appreciate that these coalitions are organized around mutual needs, loyalties, and control of power. When these subsystems are dysfunctional and destructive, such as when a parent is aligned with a child against his spouse or a child is in coalition with a grandparent against her parents, the counselor’s job is to initiate realignments in the structure and power, creating a new set of subsystems that are more functional.”

Perhaps a family dynamic really is a little like tribal warfare, or warring nations, or, better yet, a game of Risk in which every family member wants to get the most out of the family time. There are front channel diplomatic connections between father and son, daughter and mother, sister and brother. These are what we see on the board, the dynamics that play out in open air.

Then there are the backchannel dealings: Mom and dad are trying to take power away from the younger players; the youngest trying to wrest mom away from the family (with some tears and a need to be consoled, perhaps); the older kid trying to get the younger one in trouble to expose the unfairness of all the attention. The joy of Risk lies in the behind-the-scenes strategies and public lies. These are the kinds of things that can tear a family dynamics apart — that make family time so stressful.

Importantly, such power structures also take away deep connections formed during one-on-one time. When my daughter reveals her affinity to Lyra in The Golden Compass to me; when my son, rolls laughing on the floor at the block tower we just knocked down; when my wife and I sit reading on the couch, her legs on me or our shoulders touching, exchanging ideas between the silences, these deep moments, when they come, come naturally, and alone. They rarely happen during family time.

Individual bonds in families are essential, but they also don’t necessarily come naturally. “You have to organize yourself to have time alone with the child,” says Pruett. “It should be part of what you believe in fostering. You each related to your child differently, but the unique moments are something parents need to plan for.“ It takes work to get this dynamic going. But the result is quiet one-on-one moments that cut through the chaos of a family in quarantine. Right now that sound pretty damn good.

How to Better Bond With Your Kid, One-On-One

Getting solo time with your child is half the battle (in time of quarantine, maybe more like two-thirds of the battle). Here’s how to find the time — and make the most of it.

- Schedule Everything

Put it on a calendar or have a set time every week — or day — where you get face time with one kid. This is the hardest part — whether due to quarantine or just busy schedules. But it’s the essential work that is necessary to make the habit stick.

- Make It Enjoyable

“Give the child a moment where they are not sat on by the have tos but have a get to,” says Pruett. This doesn’t mean that you need to plan something exotic all the time. You just need to take the child’s interests into consideration. This could mean a walk, sitting on the porch with lemonade, or taking out the recycling together (if this isn’t an embattled chore). Keep it as simple as you can.

- Tailor the Time to the Kid

“If you give a first grader the afternoon to do whatever they want, less structure isn’t going to be that much fun,” says Dr. Robert Zeitlin, author of Laugh More, Yell Less. “You’re going to have to explain why you can’t do things that are expensive. As much structure as is necessary for choice and being able to do the time. For older kids, as little structure as necessary so they can figure time management and the realities of what’s financially possible to do?”

- This Isn’t Time For Lessons

One-on-one time is for support and listening — not being critical of anything in the kid’s life (including not paying ball in this alone time). This time belongs to you and the kid. Own it. This is the work you put in for later years — read, a healthy relationship with your teen.

- Follow the 5-to-1 Listening Rule

For every five minutes of talking, you should devote as many minutes to listen. It’s that simple — and also that tough. “For kids that don’t talk much, you just be patient and don’t bug them,” says Pruett.

- Go Deep

Once you’ve established the bond, know that one-on-one time is the time to give them a sense of who you are. What worries you? What do you believe? What are your failures? What are your successes? Why were you angry at the checkout? Why do you love country music? “These are all great questions and the answers are very important for how children will function,” says Pruett. “These are how you solve the problems of life and they need to see what you’re up to. If not, to whom do they turn?“

This article was originally published on