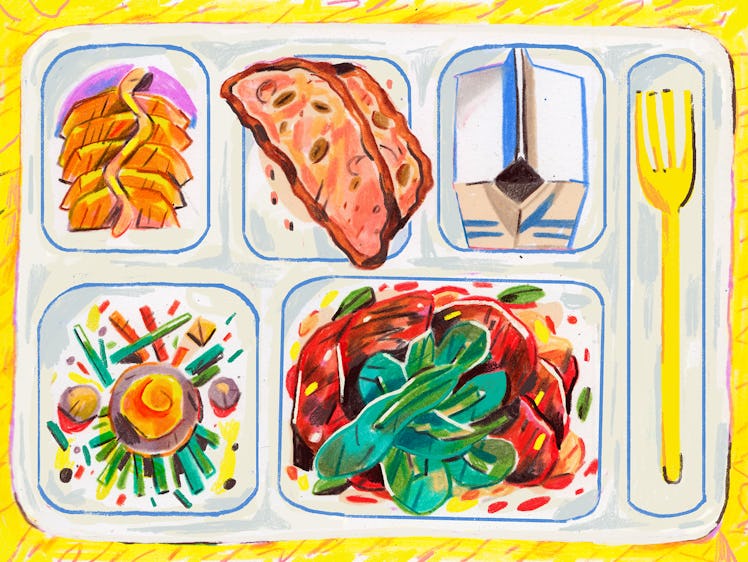

Daniel Giusti Will Save School Lunch

One of the top chefs in the world works in a cafeteria in Connecticut.

Three dollars and forty cents.

That is how much Americans have collectively decided — conscious of the decision or not — it should cost to make a kid lunch. And it’s not really even $3.40. That’s what the USDA reimburses schools for each student qualifying for the National School Lunch program, but the figure includes all costs, including utilities, labor, training, and kitchen equipment for the school staff. So the number being spent on food is actually closer to $1.20 per child per meal. Or it would be if it weren’t for the work of the powerful dairy lobby, which has carved out 39 cents per serving for a half pint per meal despite a lack of clear health benefits. So, let’s make it 75 cents on food required to hit stringent nutritional guidelines and appeal to the tastes of children.

Making that meal is the puzzle to end all culinary puzzles, which is why Daniel Giusti — really tall, kinda famous, smart as hell — spends his days in school cafeterias in central Connecticut.

Daniel Giusti has a five o’clock shadow that looks like a week-old-beard and big brown eyes that glow like embers under the mantle of heavy eyebrows. I first met Dan a couple of years ago at some event for noma, the Copenhagen restaurant which — before it closed in 2016 — was the best in the world. For three years, Daniel was the head chef there, which was like being Mike Schmidt in the 1980 Phillies or Ron Hextall in the 87’ Philadelphia Flyers. (I stopped following sports after leaving Philadelphia in 1991.) Every chef in the world was gunning for that spot. And Daniel had it. He was proud of cooking at a place where rich people had to beg for a seat, but not totally fulfilled by that experience.

Daniel Giusti is an elite chef, but he’s not an elitist or a star fucker. He grew up, in a large Italian-American family in New Jersey, remembers Sunday suppers, and wants to make good food for people to enjoy.

“Most people go to noma once in their lives and it takes a whole team of chefs to prepare their food. It wasn’t personal” he says. “That wasn’t why I got into cooking.”

Having ascended into that rare air where the plate becomes performance and the table becomes a stage, Daniel realized that the true beauty of food wasn’t its artfulness but its ability to sustain life. Daniel quit noma because he wanted to cook a lot of meals for a lot of people often. He wanted to go big with it. That meant working in an institutional setting like a hotel, prison, nursing home, or school. He opted for school because it was the hardest, the most rewarding, and probably the least depressing option. The budgets were nothing. The diners were unlikely to give him the benefit of the doubt. He founded Brigaid, an organization dedicated to making school food better. He moved back to America.

“It’s not that difficult,” he said, “I want to put chefs in schools.”

He makes it sound easy because he, renowned chef Daniel Giusti, represents proof that it can be done. But schools are just the tit-end of a Rube Goldberg-style bureaucracy. School budgets are squeezed tight and recent legislation calls for a 21% cut in funding for the USDA, which would have huge consequences on lunch. So nothing is easy and success is far from guaranteed.

I met Giusti outside the Washington Street Coffee House in downtown New London, Connecticut where he settled and located Brigaid after taking a long road trip through various school districts across the country. New London is a small New England town with little in the way of industry or rosy economic outlook. The main street is lined with pretty brick buildings now sports bars called things like High 5’s . There are 3,700 students and six schools in the district and Giusti settled on that district at least in part because they would have him. Not every administrator was open to allowing a celebrity chef into their kitchen. Educators are understandably disruption averse and previous white knight programs like Jamie Oliver’s School Revolution have run into trouble.

In New London, Giusti lucked out. The district had just hired a guy named Manny Rivera, a former Superintendent of the Year and undersecretary of education for New York State, who had returned to his hometown with big plans. Giusti and Rivera immediately hit it off. “After spending a few moments with Dan, I realized he was the real deal,” Rivera says.

He is, but, here’s the thing: Giusti isn’t just a do-gooder. You don’t get to run noma by being good or nice. You have to be driven like a demon, monomaniacal, masochistic, and little bit fucking nuts. Giusti is no Koosh ball of virtue. He’s tough. He’s doing something extremely admirable, but not cheery. He doesn’t have kids, didn’t mention a girlfriend, and has thrown himself into this project with the same intensity that served him well at noma.

As Brigaid started hiring in 2016, one of the major obstacles Giusti faced was the praise gap. Chefs like to make really good food and to be told that their food is really good. Giusti had to voluntarily forego positive reinforcement and, to make Brigaid work, he had to ask other chefs to do the same. And for what? The vague sense of doing something right in the world. Nothing much anyone could take to the bank.

“In a restaurant, when you do your job, you get praise. Here, you can’t wait for praise,” Giusti says. “You genuinely need to be doing this work because you want to do this work to make a change. If you’re waiting around for somebody to come find you and pat you on the back, then you’re in the wrong field.”

As the head of Brigaid, Giusti employs six chefs, one per school. The rest of the cafeteria workers, in an informal but clearly understood arrangement, work for him but are employed by the school. For the last year and a half, he and his team have been making delicious food for seventy-cents a serving. Well, good food. Or, at least, food that rests somewhere between what kids think is good and what Daniel, who used to run the best restaurant in the world, thinks is good. The negotiation is, according to Daniel, “a constant struggle.” There’s a lot of give-and-take but, of course, since Daniel is an adult and his clients are kids so it’s mostly just give.

“Our number one job here is to make kids happy,” he says. If that sounds like the sort of things lots of adults say, rest assured that it’s not the sort of thing that lots of elite chefs say.

How does Giusti make kids happy? He uses culinary skills and techniques that are totally new to New London’s cafeterias and maybe cafeterias generally. He also thinks about things differently. He thinks that it’s not enough to just feed a kid. He often thinks about a school lunch he saw before he started Brigaid. It consisted of a yogurt parfait, a corn muffin, a cheese stick, an apple and milk.

“The parfait really is just yogurt with some kind of frozen fruit that had been thawed out on top. The corn muffin is in a plastic bag. It is still partially frozen. As it thaws, there is condensation in the bag so it is wet as well. The cheese stick is a cheese stick, mozzarella. The whole apple is blemished and probably has the sticker on it,” Giusti sounds haunted describing this thing. “When I first saw it, I thought, first of all, it’s all cold. In a few days, it’s going to be really cold outside. Some of these kids are literally come from homes where there’s no heat. You come to school, and that’s what you eat for lunch. Secondly, nothing has been made. Outside of the yogurt parfait, which has been assembled, everything is actually presented as it was delivered.”

Daniel said he contemplated making his own muffins from scratch. Surely that was within his wheelhouse, here’s the thing about that: It’s great from a chef standpoint but completely impractical on any scalable level. It’s like calling for an armed revolution. It’s just not going to be graceful and it’s probably not going to work. Daniel, like any serious reformer, embraced the idea of incremental change. He asked the kitchen staff to inspect the apples and wash them and not to serve blemished ones.He took the muffin out of the bag. He warmed the muffin up. Then he got little baskets and he put the muffins in the baskets. These simple small changes had a huge net effect.

“The kids smelled the muffins,” he says. “It showed the kids that someone actually thought about what they eat.”

Over the year and a half, Giusti and his team have done more than heat up muffins. A lot more. Sometimes too much. Giusti recalls a hummus dish which he, and the rest of the chefs, were super pleased with. The kids didn’t like it. He tried making pizza dough from scratch. The kids preferred the pre-made versions. At one point, he served frozen pasta, a new low for an Italian-American cook. But Daniel’s whole thing is about erasing his own ego.

“When I first came here and started in, I was like, ‘I’m going to be taking pictures of these dishes,’” he says. “Then you get here, and a seven-year-old kid comes up to you and says that he’s hungry, or you catch a kid stealing sandwiches because he can bring them home to his family, and you realize what you’re doing. You really need to check yourself real fast.” The hardest part, Daniel finds among his staff, is to temper their ambition, to remove themselves and their own personal trip from the food they make. “Everybody just wants to go for the home run,” he says, “and that’s why people fail. ”

Seeing Daniel Giusti, who can hit home runs, happy and fulfilled in a New London school cafeteria hitting singles is, well, remarkable. He has, at some personal cost, made himself into a solution. He has put children first. He has made the wrong cooking decisions for the right reasons. He is, for lack of a better word, extraordinary.

It shouldn’t take an extraordinary individual to help students eat better. But it does and it likely will for the foreseeable future. The system is breaking if not broken and very, very, very cheap if neither of those things. It’s easy to see why other chefs and other advocates want to turn over the table and start fresh, but big plans are a luxury that Giusti has set aside. He functions in the present. He goes in and he does the work and things get slightly better. Maybe it’s not a policy solution, but it’s a personal one.

“Look, I’m a passionate, ambitious person who wants to be at level ten immediately” he says, “The fact of the matter is, we went from one to about a three and we’re probably going to be between four and six for the next five years. You have to start somewhere.”

Seventy five cents. That’s where you start.

This article was originally published on