The Watts Family Murder Reveals What Families Hide Behind Social Media Facades

In Colorado, a seemingly doting and loving father has been arrested for the murder of his wife and child shocking a community that saw only a happy family.

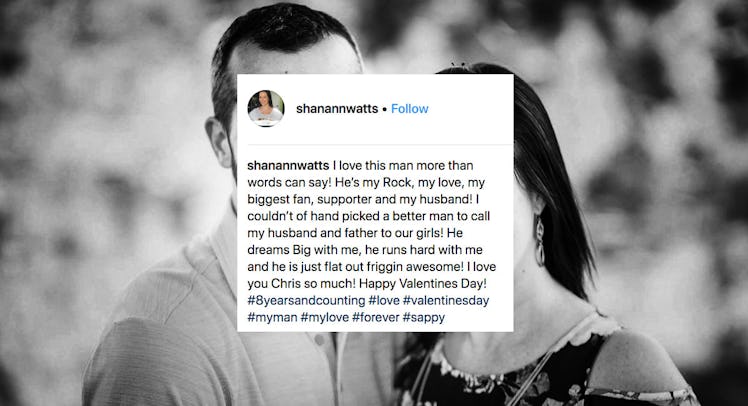

Colorado father of two Chris Watts was arrested on Wednesday and has reportedly admitted to the murder of his pregnant wife Shanann Watts and his two daughters, 4-year-old Bella, and 3-year old Celeste. His arrest has shaken town of Frederick, Colorado, a small community where the Watts were known as good neighbors, and the country. Particularly perplexing is why Chris Watts, who appeared to be a doting father would commit such a heinous act. The shock is propelled and prolonged by media outlets mining Shanann’s social media, which represents her family as normal and apparently thriving, living a life marked by travel and togetherness. In surfacing the photos and videos of the smiling and unsuspecting dead, the news leans into the pain and the deeply uncomfortable realization that when it comes to the American family, what we see isn’t always what we get.

What people saw was largely what Shanann Watts posted on Facebook. Her now memorialized page is packed with videos of her home life, often featuring a smiling Chris playing with his daughters. In one video, they play a “pie in the face” game and Chris’ daughters take turns propelling whipped cream into their dad’s face while he smiles patiently and laughs at the mess. Another video shows Chris gamely doing squats as each of his little girls, in turn, is perched on his shoulders. When Shanann became pregnant with their third child, she filmed the reveal as Chris grins broadly and laughs at her “Oops … We did it again” t-shirt. “Really?” He asks as you hear the couple kiss off camera. “That’s awesome.”

It’s no wonder then, that when Shanann and her daughters “disappeared” earlier this week, locals believed Chris Watt’s televised plea for the safe return of his family. After all, despite his calm, he said all of the right things. It was easy to believe he wanted his wife and daughters to walk back through the door. But their bodies were later found on the property of a nearby oil and gas company where Chris had recently been employed. Soon after, he was in court in an orange jumpsuit and shackles.

How can anyone possibly reconcile the tragedy and terror with the family on the social feed. When I see video of Shanann and her daughters, I smile in spite of myself. Their moments of joy feels genuine and my response to genuine joy is empathic. Then I think of the horror and how I can’t empathize with what I don’t see. I think how foolish it is to pretend that the glimpses we have into the homelives of others are meaningful. Pictures lie. Instagram lies. Facebook, it goes without saying, lies.

The murders are tragic and I don’t want to trivialize that tragedy by solipsistically recontextualizing loss. Still, I can’t help but think of my neighbors and friends — of their carefully curated feeds. I can’t help but wonder what lies beneath every carefully posed selfie or every #blessed. How much do I really know about my neighbor’s lives? If there was something wrong would I notice? Would I do something?

Look, it’s possible that the care and love Chris appeared to have for his children was genuine. He may have suffered a profound psychological break. Narratives don’t always make sense and murder never does. That said, it’s also possible he had long been acting as a perfect father while deteriorating internally. I have no idea. Chris may not even know. The questions that arise are horrible.

The question I come back to is this: Does all the artifice of social media stand in the way of real conversations and real insight? There’s part of me that thinks we have more data points and less information than we ever did before. Part of me thinks it’s all noise and no signal.

The problem is that we, as social media users, mute the struggles and amplify the joys. Of course we do. We know that feeling of second-hand embarrassment when someone shares too much. We fear committing a faux pas so we curate the representations of our own lives so that we show only the blessings and the happiness. Or we show our brave face when we are feeling less than brave. And it’s easy because we’ve been given the script. We hit our marks on Instagram. We hit our marks on Facebook. Chris Watts did.

Once upon a time, the cliche of a small town homicide was the clueless next door neighbor, who would turn their shocked eyes to the local news camera and hollowly pronounce: “He was a quiet man. Never caused any trouble.” We, at home, could either take them at their word, or vilify them for not seeing the obviously sinister signs. But, now, with social media, all of us have become that perplexed neighbor: “But they just vacationed in San Diego and looked so happy!”

Despite our best intentions, social media has made liars of us all. Not pathological liars, but circumstantial liars, conveniently avoiding the truth of our lives because it’s simply not something that’s done. Imagine if we were more truthful. Imagine if our feeds were more social and less media. Perhaps we’d be more willing to reach out, help, or intervene. Would that have saved Shanann and her children? It’s impossible to know. But it’s easy to understand that at some crucial point Chris Watts wasn’t truthful as he allegedly came to the conclusion that murder was his only option. Amongst the many tragedies in this story is that there was apparently no one who could have helped him see another path.

This article was originally published on