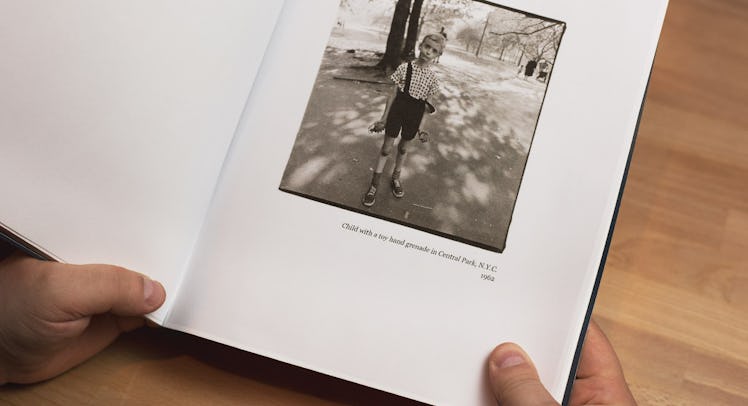

Colin Wood, Diane Arbus’s ‘Child With A Toy Hand Grenade,’ Looks Back

The portrait of Colin Wood, in which he is a seven-year-old holding a toy hand grenade, has become a symbol of the anarchist movement. How Wood has lived up to that expectation is quite the story.

It’s the tilt of the head that strikes you first. The boy is considering something, contemplating. Maybe. Maybe not. Then, it’s the eyes. How wide open they are, how they look like the eyes of a boy who’s obviously pulling a face, which he is, but also pained. Then you notice that in the heat of whatever this moment is, one strap of his overalls has fallen off his shoulder. Maybe he was running. Hard to say. Maybe he’s happy. Or sad. Either way, he’s manic and he’s holding a grenade.

Diane Arbus took many memorable photos over the course of her storied career. But when it was published her “Child With Toy Hand Grenade in Central Park, N.Y.C, 1962” made waves. It was a groundbreaking piece of work and immediately recognized as such, which is why you probably maybe kind of recognize the image. It’s an art photography touchstone commonly used in anti-war propaganda. It’s a portrait of the Vietnam War era that shows instead of tells. It’s, allegedly, what inspired Matt Groening to create Bart Simpson.

And it’s Colin Wood.

“I was mobile and hostile with a smile on my face.”

When the photo was taken, Wood was a seven-year-old kid. He’s now 63 and, when he sees that image he remembers a dark period. “That time of my life wasn’t the happiest,” he says. “My parents were divorced. I was pissed off. And I didn’t know how to articulate it. I was mobile and hostile with a smile on my face.”

Wood still has the same smile today — though whether or not it actually qualifies as a smile is debatable. One of Wood’s sons, Mulligan, who is a college student, refers to the expression as his dad’s “grimace.”

As Wood and I talk, Mulligan is eating pancakes. Wood’s wife, who is referred to exclusively as “Mumzy,” is taking an afternoon nap. The night before, he says, they ate a delicious sandwich made out of Mumzy’s special homemade sourdough olive bread with sliced roast chicken and mustard. It was nice. Ordinary.

Wood’s existence is rather ordinary these days. He lives in Los Angeles and works as a long-term insurance care agent. He’s settled down. He’s a family man. But the kid in the picture resurfaces from time to time.

“I’m not normal in a lot of ways,” Wood admits. “One time, I took all my clothes off and jumped naked into this basketball player’s pool. He was a star, a basketball star in New York. I’m a little bit rebellious or something. I don’t like being told what to do. I’m suspicious of mobs. I don’t like groups. I don’t like people with authority trying to tell me that they have a good idea, that I should put on a uniform and run at that bunker. You know what I mean?”

For better or worse, Wood’s image has always been shorthand for the angriness of restless American boys. Talking to him, this feels right on some level, but it’s clear that it was also a burden. No one wants to be that kid. No one wants to be that kid in perpetuity.

“I was always asked. ‘What happened to that kid? Did he commit suicide? Is he in jail? Is he on the streets?’” says Wood. “He’s seven-years-old and he wants to blow everybody up!”

Wood didn’t blow anything up. But it’s not like there was never a possibility of madness. Wood was born in New York on the Upper West Side in 1955. Sidney, his father, was a professional tennis player most famously known for being the only to ever win the 1931 Wimbledon singles title by default. Despite that, he was ranked more than once in the top ten greats. Sidney was also married four times. And, as Wood says, “he was stark-staring crazy.”

Wood’s parents divorced and his mother died when he was 12 so he was raised by a series of step-mothers who were of the upper-crust New York type. He became well-known as the boy in Arbus’ photo around the time he was in high school when a fellow classmate printed out the image and pasted it near the lockers. His notoriety spread. His step-family didn’t take very well to the image, nor to the way it was originally exhibited as a part of an ongoing collection that focused on unloved and stigmatized Americans.

After the last of Sidney’s divorces and after Wood graduated from college, they founded a business together that sold artificial surfaces to tennis courts all over the world. Wood, as a result, spent a good portion of his early adulthood jet-setting from Germany to British Columbia to West Africa. The two of them made good money. They also got into their fair share of “sticky situations.”

One story he tells involves his father wrestling a $75,000 water pump out of a rising river on a mining operation in British Columbia at the age of 75. Another involves Wood having a gun pressed to his head. Wood is a guy with crazy stories. There are a lot of them and there is a common theme: batshit optimism. Wood is a guy who does stuff. He may have plans, but he definitely has impulses. Always has.

“I became really close with this guy named Jorge when I was building courts,” Wood remembers. “He was going back to Bogota. He was leaving in the car. I said, ‘I don’t know what I’m going to do next, Jorge. I don’t know what’s going to happen.’ And then he said, ‘Eres muy ingenioso,‘ which means, ‘You’re very resourceful.’

“Nothing is really ever as bad as it seems, unless you’re in Baghdad.”

Wood isn’t sure, so he asks Mulligan if that’s true. Mulligan, either really believing it or just being a nice kid, assures him it is.

“Nothing is really ever as bad as it seems, unless you’re in Baghdad,” Wood says. “I’ve had guns put on me. I’ve had my life threatened. I’ve been sick. Bad things happened and bad things went away. Something’s always going to turn up. I always think it’s going to be interesting soon.”

That sentiment may not sound like it applies to his domestic idyll, but his happily family is ultimately a product of his sort of loving recklessness. “I didn’t decide to do it. I was married, and my first wife said, let’s get out of here. And I said okay. And then I bailed and we ended up in San Francisco, got divorced, and then I remarried a German.”

That German is Mumzy, who is still napping on the couch. She’s the daughter of a north-German farmer and a baker of killer bread. When Colin says he can’t believe that he married a German, she calls out, perhaps still from the couch, half-asleep, that she can’t believe she married an American.

Wood has been working in long-term care insurance since 1999. Both of his sons were homeschooled. In other words, he’s been a stay-at-home dad for their entire lives. Their bonds are strong. Their jokes at each others’ expenses are funny. Wood says they make his life crazy. But it also seems like they made his life calm. On paper, Wood’s life has settled down to a great degree. But when Wood speaks it’s sometimes hard to tell what’s real and made up.

What’s true is that Arbus captured a photo of a young boy full of frenetic energy that frightened people — that made people look twice in fear or horror or sympathy. Then that young boy grew up to be a man full of frenetic energy. A happy man. A father. A good guy. And, yes, a guy who thinks about that photograph from time to time.

“I see a future bank robber,” he laughs. “I see a sensitive soul. I see a goofball. I see the father of these two goofballs I got. It doesn’t matter. Frankly, when I look at it I sort of just see it in passing because it’s just part of my saga, the Wood Saga. I don’t really think I have any pride in it, but I don’t have any shame in it.”

This article was originally published on