What Adventurer Yossi Ghinsberg Learned About Parenting

"You don't need too much to have an agenda of how to father. You just have to be a good person."

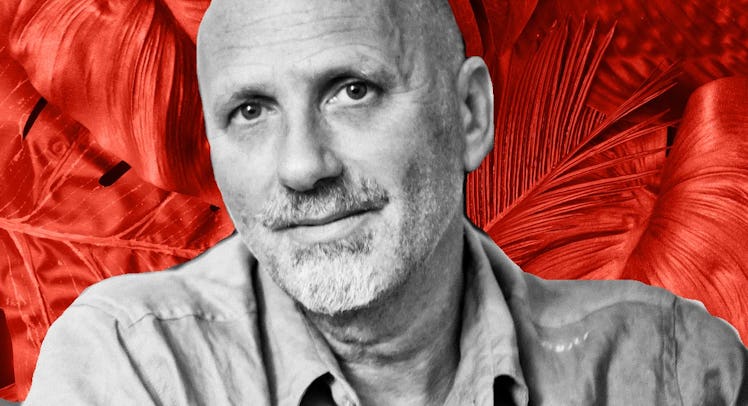

Yossi Ghinsberg wasn’t a scientist, a biologist, or a naturalist when he got lost in the Amazon for three weeks and nearly died. He was a 21-year-old man looking for treasure and adventure. It took him three months in a hospital to recover from the experience. And while a trauma like that would leave any other person unwilling to return to that yawn of wilderness, Ghinsberg actually went back to the jungle 10 years later, lived there for three years, and built a solar-powered building and developed ecotourism in the area. His book Lost in the Jungle: A Harrowing True Story of Adventure and Survival, which was recently made into a film starring Daniel Radcliffe. Today Ghinsberg is an author, activist, adventurer, humanitarian — and, most importantly, a father of four. Fatherly spoke to Ghinsberg about how his experience in the jungle radically affected his parenting style and what examples he strives to pass down to his kids.

You’ve certainly experienced a lot in your life. How have your adventures and love for the wild affect how you parent your children?

I think the main parenting or education you do for your children is by way of being, and not by way of having guidelines or some agenda. I think that life itself is constantly bringing learning opportunities. If you’re not an outdoorsy person, you’re not going to teach many survival skills to your children because it will be non-organic. But if your life involves being in nature and sitting by the fire, those skills are passed naturally, not in a contrived way. I don’t believe in any kind of teaching that is contrived.

So then you lead by example, not by teaching.

You don’t need too much to have an agenda of how to father. You just have to be a good person. The interactions at home between you and your spouse and the way you deal with your kids in certain situations, that’s what they take. Not when you tell them, “Listen to me, I want to educate you now.” What they hear and never forget are certain circumstances and situations and how you’ve reacted in real time.

What kind of examples do you think are important to you to pass down to your kids?

The story that comes to my mind right now is when I went with my father to buy a camera. We took the train to another city. It was my gift for my Bar Mitzvah. A tourist forgot a camera on the train and I found it. Naturally, I tried to run and look for the guy. When I didn’t find him, I went to the conductor and I said, “Hey, somebody left a camera.” The conductor took it. And then my father says, “You know, you shouldn’t have done that. The conductor probably took it to his home.” That example is what I remember.

In another case, and, sorry, my father, I love him, he’s my biggest mentor. I was at home one Friday night alone. I remember it was 9 or 10 o’clock at night when I heard something exploding. I went to the living room and there was a huge vase, that was the pride of the family, that just broke. Just like that. And my father never believed me. He said, “I know you broke it.” I said, “No, I didn’t!” He said, “Look, I’m not gonna hate you, I’m not gonna beat you. But I know you broke it.” And I didn’t break it! He didn’t believe me.

There are certain things about trust and certain things about integrity that you can never teach if you are not the carrier of the teaching. And that’s what the children will never forget.

If you could give your children a list of survival skills to take out into the world with them, what would you suggest?

I think we suffer from certain alienation. We live on this planet, but we somehow have an idea that we’re elevated from it, that we’re not nature. We’re a creature that manages nature and is superior and does whatever it wants. That creates a separation between humanity and the rest of the planet. Natural people don’t have [that].

The whole idea of religion is that God has created us not like the rest of the animals, but in his own image and liking. The moment that you’re a demigod, not a beast, not part of nature, not an animal, then there’s a fundamental separation which causes fundamental anxiety in general. Natural people don’t have that anxiety. The only book I’ve read as a parent is the Continuum Concept. You probably know it.

I don’t know it, actually.

[Jean Liedloff] went to a tribe in Venezuela and lived with them for a few years. She saw that this was a perfect society. All the kids that grow there, they’re good, beneficial, secure. They love their parents, love their village, and have no ego, no attitude, just very helpful, very happy. Just enjoying life. It’s like a really enlightening book in terms of what they do physically. They just tie [their kids] on their back and do whatever adults do and the kid is constantly on their back and getting their heartbeat and their warmth.

This is the discrepancy between human beings that think they’re just another animal, between another human being, who thinks they are a demigod. Natural people don’t separate their kids from them. They carry them on the body for a year, on the heartbeat, on the body’s warmth. On the skin.

And you find that to be very important.

I think this is very fundamental. My boy, at 7 years old, we still sleep together every night. My daughter was like that until the age of 8. That’s what gives the kids a sense of belonging, of everything. That total, unconditional love.

I’m trying to be down to earth and just give you: “pit two rocks together and make fire.” But I don’t have examples like that. I’m not a survival expert. If you trust yourself in real-time, you know how to deal with any situation. We’re very, very good at that. In a real survival situation, people know. They don’t have to learn. They know what to do. So if you teach them that at a young age, that they can trust themselves in real situations, it’s better than to tell them something specific. I survived without fire, without anything.

Your son is 7. How old are your other kids?

My oldest daughter is 32 years old, my second daughter is 14 years older and my third daughter is 11.

Do you feel like you’re wiser when it comes to parenting with your younger kids, or do you still feel lost?

If more experience means more wisdom, then yes. But sometimes I doubt it. Einstein was 26 when he wrote his Theory of Relativity. Beethoven, Mozart, all the great writers, they usually write their great canonic work when they’re young, not when they’re old. But I think that I have much more experience to share with my boy and yes,

With my daughter that is 32 today, I was too young. I was 25, 26 when she was born. And I left when she was four-years-old. I left home and I never returned.

That must’ve been hard.

She still deals with the trauma of me leaving. I wasn’t mature enough at the time to be a parent and I couldn’t even assume responsibility because my inner world was so shaky and I was soul-searching. At that time, I was busy with questions of my own insecurities, my own inadequacies. Certain things like that. I wasn’t settled in myself. I wasn’t a man with a sullied core. Today, I am.

Did that trauma and soul-searching come from your experience in the Amazon?

I went through big things at too young of an age, but, naturally, when you’re young you’re also adventurous. When you’re young, the spiritual desire is, “I want to get enlightened.” Naivete is dangerous and it’s what brought me the jungle experience. I wanted to be that great explorer. I wanted to be the first to explore a tribe and find riches of gold. I believed that. But behind that was desire for something even bigger — searching for myself. What I found, I wasn’t able to hold.

When you experience a miracle, it’s quite fundamental. I wanted to touch it again. I couldn’t stay home. So, initially, that trauma was detrimental. I couldn’t stay and get settled as a parent and take care of my child. I left my child with her mom and I never came back. I came to visit once a year. My kid grew without me. I say that without any pride.

This article was originally published on