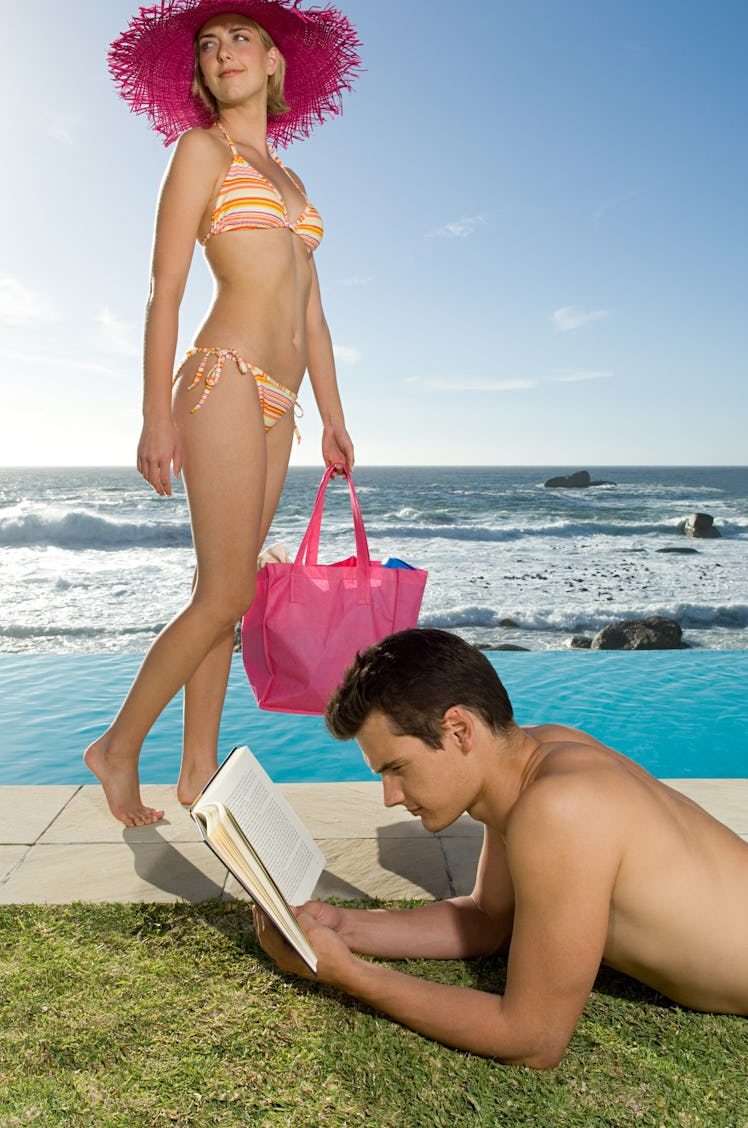

Why Wandering Eyes Aren’t Always What You Think They Are

Sometimes a wandering eye is an inappropriate stare. Sometimes, it’s part of our highly distracible brain. Here’s how to know the different.

Humans are easily distracted — and noticeably so. No matter the situation, a beautiful woman, handsome man, or moist piece of cake will grab peoples’ attention and not release it until others have noticed. This so often leads to fights over the difference between normal distraction and pathological distraction, between wanting to see and wanting too much. The accusation leveled against men with a “wandering eye” (it’s normally men, many of whom worry about this tendency in themselves and whether it will precipitate cheating) is that their incidence of distraction is abnormally high. In other words, there’s a statistical difference between a wandering eye and an observant eye. That is true, but all eyes wander so the spectrum runs from fairly distracted to problematically distracted.

When an attractive person passes by, who’s to say whether that sideways glance last too long? Before trying to come up with a succinct and socially acceptable answer to that question, factor in that it takes women 150 milliseconds to notice that a man is distracted.

Diving into the numbers, it becomes clear that distraction and particularly sexual distraction is inevitable and that it’s also inevitably noticeable. Though it may be possible to point out aberrance, it’s important to understand that “I wasn’t looking” is a dishonest and silly defense. Better to acknowledge one’s averageness and humanity than claim a superhuman indifference to powerful stimuli.

Wandering Eyes And The Dot-Probe Test

Since the mid-1990s, scientists have thrown themselves into understanding how we respond to the “sudden onset of a stimulus,” otherwise known as an unexpected distraction. Studies have confirmed what experience suggests — when something or someone draws our gaze, it’s often unintentional and against our will. “Research on stimulus-driven attention suggests that attention may be captured by particular external stimuli and that this capture may be unintentional and directly contrary to the subject’s intentions,” according to a 2014 study on the subject.

Scientists demonstrate this with the dot-probe test. Participants sit in front of a computer screen and stare at a fixation cross in the center of a blank screen. Two stimuli then appear around the fixation cross, one neutral and one distracting. These two stimuli remain on the screen for about half a second, until one stimulus is replaced by a dot. Participants are instructed to tap the keyboard as soon as they see the dot, and the lag between the appearance of the dot and their tap estimates how distracting they found each stimulus.

Studies of hungry participants have shown that people respond to the dot-probe test faster when presented with food-related words. And research involving pornographic images has shown that people with compulsive sexual behaviors have a delayed response to the dot test, indicating higher levels of distraction.

But for our purposes, the dot-probe test can also answer the question of how long a gaze is too long, and when a distraction shifts from normal to near-compulsive behavior.

How Long Is Too Long?

Dot-test studies have shown that we take at least 50 milliseconds to shift our attention from one cue to another, and at least 150 milliseconds to shift our attention when a cue requires us to look away in order to capture it. And, generally speaking, if it takes someone about one second to notice a new stimulus, experts assume this “may reflect multiple shifts of attention, reflecting disengagement and maintenance of attention.” So if you’re driving and a fly goes splat on your windshield, you’ll notice it in approximately 50 milliseconds. If a deer appears in the corner of your eye, noticing that will take a slightly longer but still imperceptible 150 milliseconds. And if you’re lost in thought when that fly or deer appears, it may take you about a second to notice it.

But once you’ve noticed the object, how long does it take before your mind becomes capable of dismissing it? To use a slightly different example, if you’re driving down towards Atlantic City (sans flies and deer) and a provocative billboard appears, we already know that, if it’s in your field of vision, it’ll take you about 50 milliseconds to notice it. If it’s off-center from your windshield, it’ll take more like 150 milliseconds for the sexy image to register. So at what point is the earliest that you could possibly avert your gaze?

The study of response time to pornographic images found an answer. Even among participants primed for compulsive sexual behaviors, the ability to control one’s gaze didn’t kick in for at least 450 milliseconds. So the earliest we can be expected to look away from a sexual image is about half a second after first seeing the image (and 300-400 milliseconds after being distracted by it).

The numbers alone suggest that, most of the time, your wife is going to notice that you’ve given another lady the once-over long before you even have the ability to avert your eyes. Examine the numbers. If it takes you 150 milliseconds to notice a cute cashier, it takes your wife 150 milliseconds to notice that you noticed. But you can’t control your gaze until 450 milliseconds in — which is 100 milliseconds too late to cover it up.

But the real reason this doesn’t really help is that we’re talking milliseconds under laboratory conditions. In the real world it might take your eyes significantly longer to wander. That’s not an excuse. The focus here should really be the person falling into your field of vision. One study suggests that eye contact for longer than 3.4 seconds is universally considered creepy, so if the subject of your distraction is a person (as opposed to food or a billboard) always turn away quickly. That’s clearly way too long. If your gaze is making people uncomfortable, it’s never healthy. So if your brain causes you to stare, look away as fast as you can. 450 milliseconds should about do it.

This article was originally published on