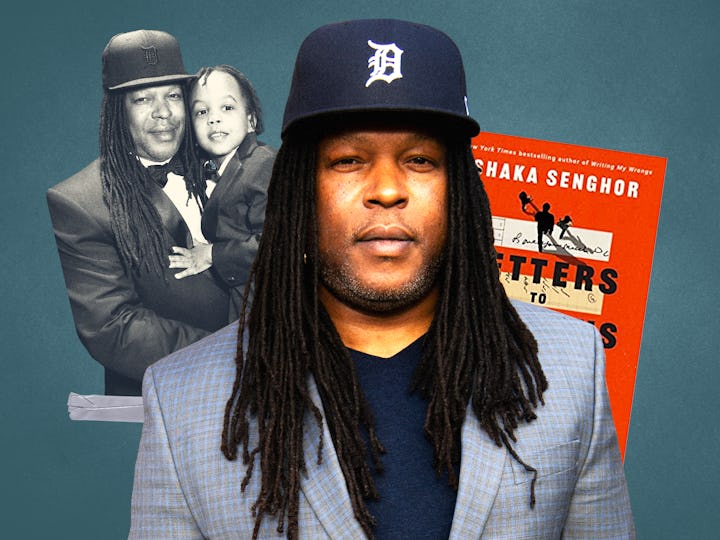

Shaka Senghor Is Inviting You Along On His Journey Toward Vulnerability

The author and advocate’s second book is a window into his relationship with his sons that he hopes will change how men view emotional presence.

Throughout the 19 years he was in prison for committing second-degree murder, Shaka Senghor’s dad regularly wrote to him. Today, the New York Times bestselling author, public speaker, presenter, and criminal justice reform advocate views those letters as one of the foundational elements of his healing and transformation.

“We were able to grow to understand each other,” Senghor says. “We were able to debate, argue, laugh, and see our relationship as father and son grow through the written word. You experience a level of intimacy when you read or write in a letter that you just can't get to in any other format.”

Written correspondence was such a powerful force in Senghor’s relationship with his dad that he structured his recently released book Letters to the Sons of Society: A Father's Invitation to Love, Honesty, and Freedom as letters to his two sons. The collection outlines his experiences as a Black man in America and processes misguided paradigms about masculinity, mental health, love, and success that young boys absorb from the world around them.

Senghor's oldest son, Jay — now 30 years old — spent most of his life with his dad behind bars. That separation pained Senghor but also motivated him to embrace the hard work of multifaceted reconciliation, which he writes about in his first book, Writing My Wrongs: Life, Death, and Redemption in an American Prison. It’s a story that, at 10 years old, his youngest son, Seku, didn’t have to live, but that certainly shapes who his dad has become.

Fatherly recently had the chance to visit via video chat with Senghor about Letters to the Sons of Society, and how he hopes the book will help fathers and sons experience the healing that can result from developing relationships with other men that are grounded in emotional awareness and mutual vulnerability.

The vulnerability and honesty in your first book really struck a chord with readers. What prompted you to dig into those traits even more with both the content and format you choose for Letters to the Sons of Society?

You know, the way that I've always thought about anything I share is that it's only worth sharing if I can be my true self and if I can be completely raw. And to your point, the first book came down to what I went to prison for. I know how devastating that was to my family, how devastating it was to David's family — the man whose life I'm responsible for taking — and how devastating it was to the community. I wanted to peel back the layers so that people could understand how a kid who was on a path to be anything he wanted to be in a world could end up becoming a wayward child who lands in prison.

Letters is really just about looking at my beautiful 10-year-old son with everything happening in the world and knowing that I wanted him to understand all of who I am as a dad. At 10 years old, sons are typically looking at their dads as superheroes. But I wanted to deconstruct who his personal superhero really is beneath the hood.

And then for my oldest son, it was to help him understand this ghost of a man who kind of played in the background of his life because I was incarcerated for 19 years of his life. And I just felt like I owed them that truth and the complexities of all the things that make up who their dad is.

When you were writing Letters, did you share chapters with your sons along the way, or did they read them when the book was in its final form?

The process was very insular on the writing side, thinking about what stories are important for me to share with my sons. My 30-year-old son, he's a young man. I told him what I was writing and asked him if he was interested in reading it. At the time, he wasn't.

With my 10-year-old son, I don't think I let him read anything until I wrote the intro, which was like the last thing I wrote. And hands down, to this day, his reaction is probably one of the best reactions I've ever gotten from anybody who has read my work. I mean, he's 10 but he comprehends what I write in a very authentic way.

He found the intro amusing and funny and got some insight into things about his granddad. It was just beautiful. But for the most part, I just wrote the letters with the idea that when my sons are ready, they'll read them.

You paint a vivid picture of your feelings in Letters. The emotion is inescapable, like in the story you tell about how you processed the time Jay was brought to prison to meet you for the first time, but as a toddler, he didn’t want anything to do with you because you were, as you describe it, a ghost to him. What did you learn about vulnerability while working on this book that you hadn't known or fully understood up to that point?

I would say the biggest lesson that I learned about vulnerability is that I feel so much responsibility as a dad. I feel this enormous weight of wanting to make sure that I get it right. I've come to see that vulnerability is terrifying all the way up until the point that you leap off the edge, and then it becomes beautiful, and it becomes magical and it becomes powerful and empowering in a way that nothing else I've experienced has been. It's one of the most liberating forces.

For men and dads, it's terrifying to take that leap. But once you leap off the edge you realize it’s actually amazing. Like, the views here are quite stunning. As so through this book, I explored how I want to experience fatherhood. I want to feel liberated and emotionally available to my sons in a way that really empowers them and honors their existence in the world.

Speaking from experience, emotional availability is hard. What does it look like for you to learn how to be more comfortable in a vulnerable posture? Because a lot of guys who are dads now didn’t see that from older men in their lives growing up. We're trying it as we go along, but it can feel clunky. What's been your learning process for raising your comfort level with emotional availability?

I think for me, it’s different than it is for most people. Seven of my 19 years in prison were spent in solitary confinement. And from the very moment of my arrest, there was a stripping of my humanity. There was this unveiling of my physical being with the degradation of being strip-searched and stripped down. And so, over time I had to build in myself a resolve to really maintain a sense of what it means to be human in a very barbaric environment. And that willingness to fight for my humanity manifested in the form of a journal that started just with an essential question — “How did I end up here?”

That seems like a deeply philosophical question to jump in with. How did being honest with yourself as you explored that question help you in your journey?

So my willingness to explore the pathway that led me to incarceration was a primer for the level of vulnerability that comes out of my writing and that shows up in me as a dad who at one point had been stripped of everything. I’ve been able to patch up my life with the words and wisdom of other people and through this kind of sacred journey of journaling. It revealed to me that at our core, we're naked human beings that are constantly trying to figure out ways to cover up the essence of who we are because we're afraid of how we will be judged. And a lot of that judgment is self-imposed.

That realization through journaling really opened me up to the fact that I only wanted to move through the world in a way that authentically honors who I am as a person, and that honoring starts with how I view myself.

As you're modeling vulnerability for your sons, do you ever have intentional conversations with them to destigmatize some of the current notions of emotional health that men can be reticent to dive into just because of either apprehension or societal standards?

Yeah, in one of my favorite chapters in the book, I really talk about discovering that my ultimate responsibility is ensuring that my youngest son has full access to all of his emotions. Making sure he's actually comfortable using the word “sad” is really important, especially for young boys.

Last year was a really, really tough year for our family. My brother was murdered. And then our puppy was killed. And the morning after our puppy was killed, I sat my son down on the couch and started off with, “I'm really sad. And I'm sad because I have to share some news with you that’s really, really sad and heartbreaking.”

As I’m sharing the story, he let out the kind of cry that no dad wants to hear, right? The type of cry where you know there's not a hug big enough to soften the pain, and so I just had to hold him and sit with that and allow him to sit with the sadness.

We really get into the emotional process of grief and I explained to him how there'll be moments where you'll remember our puppy and find yourself in this extreme space of joy and then it'll collapse on you like a building, and it'll be sad because that joy isn't tangibly attached to being able to go and pet your puppy or take your puppy for a walk.

That’s such an important lesson.

That's the reality of being emotionally balanced. That ability to find sadness within your joy and joy within your sadness.

I learn so much about myself through these moments. And I know as a dad and as an author, my hope is that other parents will really lock into how much our boys specifically need space for all of those emotions.

You’re not only practicing emotional awareness and trying to share it with other people through your writing, but you are also inviting people into that practice by encouraging other fathers to write letters to their sons. What do you hope will come from that?

Yeah, I'm launching a campaign called Love, Dad in the near future and inviting other dads to join me on this letter-writing journey to our kids. I think the wisdom of dads has not been showcased in a way that's always accessible. And so what I want to create is something that's really accessible to dads all over and more importantly to the children who needed to hear from dads other than their own. Because sometimes wisdom from other dads can hit hard and help you see your own relationships in a different light.

That’s a unique way to actively take your own writing and use it to build momentum for something bigger.

Thanks. And it’s not just me. We have some notable dads helping us launch the project like Charlemagne Tha God from The Breakfast Club and the singer Aloe Blacc. And they're bringing it! They're really emotionally vulnerable. I'm like “Bro, why did you send me this letter so early in the morning? Now I’m sitting here crying!”

It’s beautiful to see that level of honesty and vulnerability come alive on a page. I feel so honored that they trust me with the gift of their hearts. And so soon we are going to invite dads from everywhere, and I hope we get a million more letters like that.