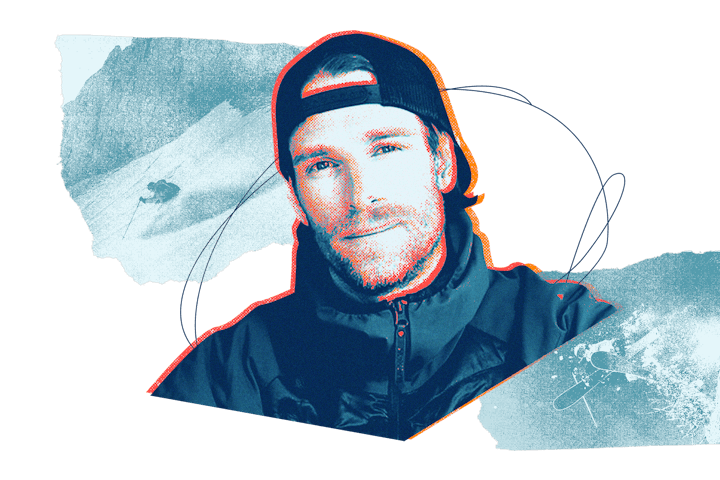

Matthias Giraud Gets Down To Earth

Matthias Giraud is the most pragmatic, cool, calculated — and just plain greatest — professional ski BASE jumper dad on the planet.

Matthias Giraud isn’t in it for the rush. This might come as a surprise from someone who’s dedicated much of his life to merging two of the world’s most extreme athletic pursuits: big-mountain skiing and BASE jumping. Giraud has pioneered the field by climbing some of the world’s toughest mountains, only to ski off their peaks and float down into the valley below by parachute. But nothing that Giraud does is unconsidered or reckless. He’s a sort of poet philosopher of risk, passion, and the pursuit of one’s dreams. He aims to mitigate the first, maximize the second, and to constantly reevaluate and never veer from the third.

Giraud was born in Évreux, France, in 1983 — his father, a former paratrooper, had gone reluctantly to medical school, after an injury derailed his dreams of becoming a pilot. Watching regret shape so much of his father’s life, Giraud resolved to do something radically different with his: He would pursue personal fulfillment at all costs. “Don't ever apologize for how you feel. And don’t ever let fear stand between you and a passion,” Giraud later wrote in a letter to his son.

This lead him to Mount Hood, Oregon, where in 2008, he launched himself off the infamous Mississippi Head, a 250-foot cliff, with a chute — and then launched his career. One year later, his son, Sören, was born. No, Giraud didn’t change his ways. Why would he? From his point of view, his profession is pursuit in the highest level of risk mitigation. Besides, the alternative would mean ditching his passion and in his telling, following his own father into a life filled with regret.

Giraud tours with not just his skis and chutes, but a willingness to expound his philosophy, something he brings to the world through film (his latest documentary, Adrenaline Sucks, is doing rounds in film festivals now and explores this very notion), panels and talks, and by example. His son, is now a 10-year-old skateboarder, skier, and climber who is by all signs following his lead.

When we spoke to Giraud he, unsurprisingly, had a full schedule ahead of him, preparing to head back to the Alps with the aim of checking off a few ski BASE jumping firsts, to shoot a few video concepts, and to do his first live ski BASE jump at a Back to Back Invitational. But first, he would spend some time in Oregon on the slopes with his son.

What’s your favorite thing to do together as a family?

Every week that I have my son [Giraud co-parents with his ex-wife], we go rock climbing. It’s something I got back into last year. He’s already climbing 5.11+ and we have a great local climbing gym. I’ll put him on belay and he’ll go up like 15 times. He really gets the power of introspection of focus that gets with intentional high intensity activities.

The fact that you’re belaying someone, well, they’re putting their lives in your hands. Sören is too young to belay now, but he understands that to be on belay it to accept to put your life in someone else’s hands and think about how and why you trust this person.

If you have an hour yourself, what are you doing?

Well, I have the privilege to always connect my mind and body and heart. Because of the nature of my profession which is more of a vocation I never disconnect. I call it aligning my conscious and unconscious. I’m always proactively working on something or putting the pieces in my head together. I am training, working on a project, or conceptualizing.

I’m a very driven, intense person with high ambition. But I also always find time to chill. If I need to take an hour nap, I take an hour nap.

What’s your favorite piece of clothing or accessories that you own?

Every day I wear my climbing mountain belt. I don’t use a street belt anymore. I have a metal punk style. So I always have my leather jacket. But since my studded punk belt broke I wear one of my two climbing belts — an all black Grip6 belt or Black Yak climbing belt. It’s another way to never disconnect.

Name the most important skill you’re passing down to your kid/kids.

To avoid decision fatigue, or the problem you get when you have too many decisions to make and you can’t anymore. We can do so many things that we don’t know what matters anymore, what we like. What are the top three essential things to you? For me, it’s 1. True love has always been important. 2. My vocation. A passion. A passionless life is worthless. And then obviously 3) fatherhood and my son.

The key to avoiding decision fatigue is to keep these three things in mind. This is my existential triangle — and I aim to keep it equilateral. Otherwise life lacks balance.

Give us a book, record, movie, or TV recommendation.

Anyone going through a deep moment of introspection or recovering Man’s Search For Meaning by Viktor Frankel. It’s very Jungian and deeply impacted me and is something I revisit.

With my son, we read French books together. (I only speak French with him.) We’re reading Titeuf’s guide to sexuality. This comic book explains relationships, feelings, and sexuality and it explains concepts and things that are difficult but essential to explain to a child.

If you could give one piece of advice to your former kid-free self, what would it be?

I would say, learn to enjoy every stage of growth with patience. I’m such a goal-oriented person. I’m climbing that mountain, finalizing that project. Well, a child is an ongoing project. It’s not something that you get to your goal and you’re done. You have to learn to connect with your child through every stage of your growth. I think I've always been a very dedicated father but it was sometimes out of duty and love instead of true enjoyment. Learn to be dedicated to your goals and your achievements but also learn to have equal dedication to connecting and bonding with your child. Spend the time to talk with him. Do it without something else on your mind. That will create more productive growth.

This article was originally published on