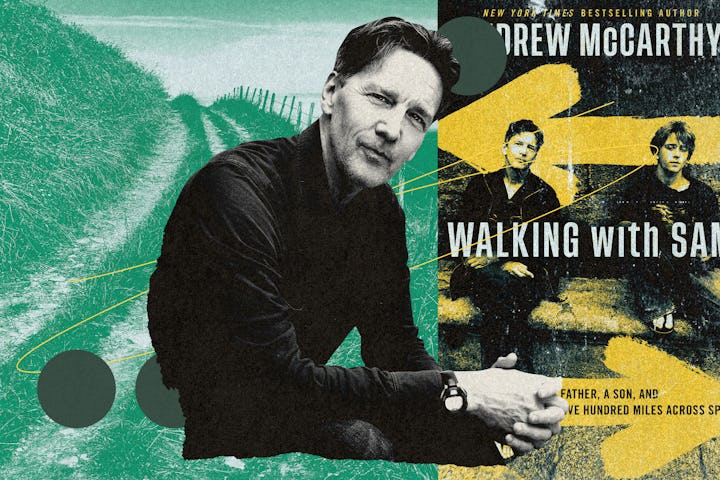

Andrew McCarthy Walked 500 Miles With His Son. It Changed Everything.

The actor, writer, and director discusses his new travel memoir, forging a stronger bond with children, and the hardest, most important thing a parent can do.

When he was a younger man, Andrew McCarthy set off alone across Spain’s Camino de Santiago. He was at a crossroads in his life and wanted to challenge himself on the renowned route, to prove that he could accomplish something on his own. Yes, he’d achieved success as an actor in such films as Pretty In Pink and Weekend At Bernie’s, but he couldn’t shake the gnawing sense that he hadn’t done the work to earn any of it. His Brat Pack reputation didn’t help. He’d read about the Camino, a 500-mile route that retraces the steps of medieval pilgrims who journeyed to the Cathedral of Santiago de Compostela in Western Spain, and decided that would be his proving ground. The route begins in France, winds through the Pyrenees, and crosses almost the entirety of Spain from east to west. It’s hard on the body and the mind. McCarthy was largely unprepared. He succeeded. The experience changed his life.

“For so long I had felt ill-equipped, insufficient in some way, and often very alone,” he writes in the introduction to his new book Walking With Sam. “It took the Camino to teach me that I was solid in myself.”

Twenty-five years later, McCarthy, now a respected director and author, as well as a father of three, set out on the Camino again. Except this time, he wasn’t alone. With him was his 19-year-old son, Sam, who he shares with his first wife, and he hoped “The Way” would educate him again. Sam, an actor in his own right, was on the precipice of adulthood, and McCarthy wanted to share the experience with him as well as try to form a new, more adult bond.

Their trip, chronicled in Walking With Sam, is full of ups, downs, bickering, ball-busting, blunt honesty, frustration, long silences, deep discussions, apologies, and laughs. Ultimately, it helped each of them to form a fresh perspective of the other. A long-time travel writer for the likes of National Geographic, McCarthy tells a good story, peppered with lovely anecdotes about the path, and the father-son relationship feels authentically captured. Perhaps his most notable act is how, throughout the tale, he openly he wrestles with his emotional baggage and frustrating tendencies and lays bare the complicated way parents can accidentally block themselves from forging deep relationships with their children.

Fatherly spoke to McCarthy about the journey, discussing difficult topics with your kids, the art of calling yourself out, and the beauty of just listening to and learning about your child without judgment.

This was your second time walking the Camino. What was that first journey like for you?

I hated it. Really, I hated it. I got there and it was miserable. After three days I had some bleeding blisters that were so bad that I had to stop in Pamplona for four days to let them heal. I was utterly ill-equipped emotionally and mentally for what I was doing. And I would've gone home except I'd bragged to my friends that I was going to go walk across Spain for a month. I couldn't show up after four days and go, "Oh, I changed my mind."

But then in the middle of Spain, in the high Meseta, there are these fields of wheat that go on for days at a time and that area is known to drive people crazy. I mean, that's where Don Quixote was in such a state, that he was wandering around and you could see why he was tilting at windmills. It's scorching hot and you're just out there alone and your brain wreaks havoc on you. And I just fell down.

I had a sobbing temper tantrum, and I didn't know why I was so upset. And slowly as I was sitting there, after I sobbed myself out, alone in this field of wheat, I realized how much fear had dominated my life. And that was a real revelation to me, I never even knew fear was a factor in my life until that moment, of its first absence.

That’s a big moment to have.

It was. And then from then on, I skipped across the rest of Spain. The trip transformed in that instant and I had an amazing experience in the second half of the journey. That led me to continue traveling, which turned into travel writing and that was a game changer for me entirely.

All anyone ever wants is to be seen, right? It's just like, "See me, hear what I'm saying, see me." And I think it's hard to do that with family.

And so there you were, 25 years later doing the same journey with your eldest son, Sam. What about you and Sam's relationship prompted this walk?

When I was 17, I left home. My relationship with my father essentially ended at that moment. It’s one of the bigger regrets of my life and I didn't want that to happen with my kids. I had no template for how to have an adult relationship with my own kids. As Sam was getting ready to go out on his own into the world, I thought I would like to try and transform this. He's not in a position where he was going to tolerate or be interested in me parenting him hard on a day-to-day basis. And I was not interested in that anymore, that wasn't necessarily what's called for. That's why I wanted to try and transform that relationship, to some degree, and basically, just see each other.

Sam said one time — I think this is in the book — that it takes a long time for kids to see their parents as real people, if ever. They look like us and they kind of behave like us to some degree, so they must emotionally be feeling what we're feeling. And it's just not the case, and we don't even know we're doing that to them.

All anyone ever wants is to be seen, right? It's just like, "See me, hear what I'm saying, see me." And I think it's hard to do that with family.

Father and son on the Camino

This trip provided you that opportunity. And you try — and largely succeed — not to parent him too hard but just learn who he is and teach him who you are.

Yeah. I had the opportunity that you very rarely have with adult children, which is the luxury of time. I didn't have to solve things. I didn't have to, "Okay, here's what we do here. Here's the fix, here's what you do." I didn't have to be pounding advice at him. I just walked and I just knew I could just walk beside him, let him talk, and go, "Yeah, that sounds tough and whatever." And just be there for him so that he can talk himself into what he needs to learn from something.

So, I wanted to have a foothold as we moved forward into an adult life, from which to go forth. It didn't solve and change the relationship, but it would give us a new baseline of, "This is where we're going to go forth from, from now on." And that seems to be what's happening.

You and Sam cover a lot of topics very freely that some parents might scold or lecture about or avoid altogether. Sex. Ayahuasca. Divorce. Cigarettes. You don’t lean towards casual acceptance and express concern but you mostly listen and reflect and accept. How difficult was this for you to not go “full dad”?

Well, do I want my kid smoking? No. Did I smoke for 15 years? Yes. Did I want my kid then going out and saying, "I'm going to go make a call,” and go outside to smoke and hide it from me? I mean, the whole point of the thing is that we learn and see each other. I just go, "You're an idiot for smoking. You know that?" And he's like, "Yeah, I know."

There's nothing else I can say there. And accepting who he is and what he is going through allows him to then come to me. Otherwise, if I'm just going to still judge him, that won’t happen. The majority of kids are going to try drugs and alcohol, and it's a slippery slope for anybody, and it's the most terrifying thing for parents, I think. I was a complete alcoholic when I was young and it almost destroyed my life, destroyed my career. And am I terrified that can happen with my kids? Absolutely. But the most you can do, in my mind, is be there and go, "Okay."

It's so easy, particularly with loved ones and family, to just deflect and misassign your crap onto them. That's what we do all the time.

That’s a big part of it.

And if they talk to me about it, at least they're processing and you're communicating and you're having a relationship. Otherwise, they're just going to go up and do what they do and shut you out. I wasn't interested in that.

Do I want him to be going to Ayahuasca? Frankly, I wish I could go do Ayahuasca. I never did it and it sounds amazing.

I'm not sure what the answer is, but I know it's not in my experience to just shut someone down and say "You're an idiot, don't do that." Because then they're just going to turn off to you and go away.

I think you really capture what a lot of men struggle with when trying to connect with their kids and getting angry with themselves. I imagine that a lot of this came as you were writing this book in retrospect. Was this process of confronting some of that behavior or realizing that cathartic for you?

Well, years of therapy, right? (laughs) It's so easy, particularly with loved ones and family, to just deflect and misassign your crap onto them. That's what we do all the time. So again, I wanted to be able to see him, I also wanted him to see me and to own stuff. You have to own what's yours.

Easier said than done.

Absolutely. And there were times in the book when I didn't, when I just deflected on him and gave him shit for something and didn't own my part in it. If the goal is to create an honest, open dialogue between people and intimacy between people, you have to be truthful with them as much as you can. And we're constantly slipping and doing dumb things and just cleaning up your side of the street.

So, I don't know how to answer it really, except trying to be awake and, I don't know, just do the right thing. You know what I mean?

It takes a long time for kids to see their parents as real people, if ever.

I do.

Yesterday, I took my nine-year-old school and we're getting out the door, we're late, we're getting out there door and he goes, "I got to poop." I'm like, "Oh, Jesus fucking Christ." So, he's going to the bathroom. I look at my phone while he's in the bathroom and I get some bad news that I didn't really want to get. Nothing catastrophic, but just like, "Oh, shit. Okay, I got to deal with that." And suddenly I'm yelling at my kid to hurry up, I'm, "Come on, we got to go."

And it's like, "Well wait a minute, he's not doing anything. The kids' got to poop. He's fine." And because I got bad news, I'm miss-assigning bad news, that frustration onto him, and now I've got a conflict with him that is not his fault. He's looking up at me like, "Why are you upset with me?" And he's in tears because I yelled at him and I'm totally wrong. So, then I have to go, "I'm sorry, I just got bad news in this thing at the last second." And that's all we can do is kind of fuck up, clean it up, fuck up again, and hopefully, make different mistakes.

I think that’s life in a nutshell.

Yeah.

Thank you for sharing that. I think a lot of parents can relate. Back to your walk with Sam. What do you think you came away from this trip knowing more about him, and what are some of the bigger moments that you now, as you said before, have these handholds now?

Well, he has real emotional courage and I think that'll stand anyone in good stead. And I admire him a lot. I feel less fearful for his future, I suppose.

And what did you learn about yourself during this trip? What surprised you?

I really tried to not press so hard for answers and get things done, to try and create some internal space because I think a frontal assault is not always the answer. And I don't know how to be more specific than that. I think it goes back to the word trust. That if your intentions are right and you're doing the right sort of things, the process will take care of itself. I guess trusting my own experience. Trusting his experience. Trusting our experience is enough. And in many ways, we're fine and that's okay. Fine is okay.

Do you think your work as a director has helped you become a better parent?

That's interesting. The more I direct, the more comfortable I am at directing, the more I know when not to say anything yet, when to step in and talk. Somebody will come up to me after a take and they'll go, "Well, they're still doing this." They'll put in their two cents. "They're still doing this." I'll go, "Just give them a second, give them a second." And just go, "Let's go again." And let them sort it themselves. Invariably, the answer's going to be stronger and better if people find it themselves than if they're told. And it's a fine line of, When does one step in and when does one just hold the space and let them find it? And that's parenting, as well as directing, I suppose?

Absolutely.

That’s always the trick. And that's only done by experience, is when to know when to step in and when to know to let it go and not have to come in and fix it for your own ego to show that you know better. That not what the fucking job is — directing or parenting — to show that you know. The job is actually to help them get where they need to go. It's not about proving that you know best. And I think a lot of us do that all the time, to show that we know and it's hard to not want to be the guy, when it's like, "Let them do it." It’s hard to do. I find it’s hard to do.

Yeah, and that parallel is quite clear. And for the trip, you succeeded and walked those 500 miles. And Sam, although he was not into it at first, fell in love with it and went past Santiago to Fisterra. He goes on without you. That’s a poetic moment.

Huge. And that's when I knew I had a book, because that's what all parents want, our children to succeed us and be the first one to go to college, the first one to become a doctor, whatever. That he would go beyond where I was going, to go do that? That was a beautiful thing to me.

You had the opportunity to do Camino twice in your life, once as a young man and once as an older one. Looking back now, what advice would you give to your younger self?

Probably the same advice I'd give to myself now, which is, "You're fine, don't press."