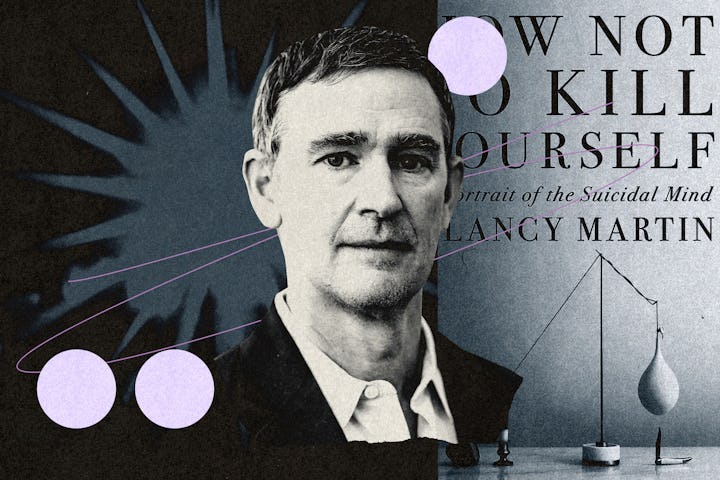

Clancy Martin Is Making Peace With His Suicidal Tendencies

Depression is something one lives with, not something we can eliminate. Martin helps us all understand this — and build a philosophy to combat it.

Clancy Martin has attempted suicide more than 10 times in his life. To speak to him, you wouldn’t know it. You would have no clue the pain he struggles with — the constant anxiety, depression, suicidal ideation, and self-loathing. He’s one of the most cheerful people you could ever have the fortune of meeting. In fact, most of his friends had no idea of his inner demons until he published a book on the matter, How Not to Kill Yourself: A Portrait of the Suicidal Mind, in March of this year.

Trigger warning: This post contains discussions of suicide, including suicidal ideation and suicide attempts.

Martin is far from alone in his struggle. About 1 in 10 men will experience depression or anxiety, according to the Anxiety & Depression Association of America. That’s less than the proportion of women who experience these conditions, but because of the stigma men in particular face about being vulnerable, sharing their emotions, and, yes, seeking therapy, they’re much more likely to die by suicide — 3.5 times more likely to die by suicide than women.

Depression can develop at any point during a person’s life, but the median age of onset is between ages 30 and 35. For Clancy, however, depression has been with him as long as he can remember — since he was at least 6 years old. It’s a part of family life too: His wife and many of his five children have mental health issues. But lived experience isn’t all that makes him an expert on depression and anxiety. As a philosopher at the University of Missouri at Kansas City, he thinks about human experience more than most — but most distinctly, he draws perspective from an incredibly eclectic range of sources, from Buddhist parables and to the teachings of the great existentialist Soren Kierkegaard.

His personal and professional experiences have led Martin to become a sort of de facto leader of a group of men who are dealing with mental health issues and who serve as unofficial therapists for each other. And through his book, he’s expanded that group to include “anyone who in some way orbits the dark sun of suicide,” with the hope that “it will encourage you to keep on going, even when things feel hopeless.” Because after years of trial and error, of suicide attempts and survival, Martin has found strategies, rules, resources (some profound, some very practical), and ways of connecting that help him limit the terrible impact depression and anxiety have on his life — and hopefully yours too.

Here, in his own words, Martin walks us through the lessons he’s learned from his own philosophizing and from great thinkers of old, and how they have helped him learn to live with depression, anxiety, and suicidality.

Hey there, little depression. Don’t worry, I got you.

Suicidal ideation is with me constantly. It’s the background noise of my life. Even my earliest memories as a child are colored with the desire to kill myself. Sometimes my passive suicidal ideation can become more active suicidal ideation, then planning, and then an attempt — it all has to do with escalating levels of anxiety and depression.

The year in my adult life when I made the most attempts, which was 2011, I was in the midst of basically a panic attack and a severe depressive episode that entire year. At a certain point, the suicidal ideation would just make me think “I’ve had enough,” and I’d make an attempt. It’s a miracle that I survived that year.

My anxiety works in much the same way. It’s a constant thing. It’s not something that’s ever going to go away. I notice when I’m more anxious and when I’m less anxious, but I’m never not anxious. It’s just a question of how anxious I am.

For me, it’s hard to sort out the difference between a high level of anxiety and a low grade of depression. They feel very similar. I also think that a certain hum of low-grade depression is with me most days. But it’s quite low-grade. It’s not menacing; it’s not threatening. It’s just when it decides to get mean, it gets mean. And I do try to notice that it’s there and say, “Hey there, little depression. Don’t worry, I got you. You’re welcome to stay right where you are. If you want to get really big, you can, but I hope you don’t. I’m doing what I can to take care of you.”

My depression and anxiety are very similar to one’s experience of physical pain. Like you think, “Oh, my God, I’ll do anything to get away from this.” When that happens, it rears its head as an enemy. And what I’ve learned to do for me is rather than running away from it, I try as much as I can mentally to go deeper into it. I think, “What are you really feeling now? What are the contours of this pain? Do you see any particular sources of it?”

I try to welcome it. I try to say, “I’m glad you’re back, my depression. As painful as you are, I’m glad you are here. Now we have to spend some time together.” I try hard to do that, not because I wish I could say that I genuinely do welcome it — I don’t; it’s horrible; I hate it, and sometimes it sucks so bad, I can’t go on. But that’s what I try to do because I found that that is what helps, and for me, that’s what has a tendency to shorten these episodes rather than prolong them.

This day is today.

There’s this parable, one of the early parables of the Buddha, called The Parable of the Two Darts. The Buddha in this parable says suffering is like two darts. The first dart is the suffering itself, and there’s absolutely nothing we can do about that. There’s going to be lots of suffering in life, he says — get used to it because that’s not going to change. The second dart is the suffering we do over suffering, like the running away from the suffering, the fear of the suffering, all the adding to the suffering that we do by the way we react to the suffering. And the Buddha says that second dart is under our control. The thing that we, according to this parable, need to learn to do about that is to learn how to accept pain rather than fight against it.

I’m trying to learn how to be grateful for my depression. There’s another philosopher, a Danish philosopher named Soren Kierkegaard, who said we absolutely have to learn to be grateful for our depression. He called it “despair.” So why should we be grateful to our despair, to something that is so painful? He thought it’s because that’s how you cut through all of the habits of ordinary life that cloud you to the reality of who you really are and what your opportunities are for loving yourself and for loving other people — that without it, you have a tendency to fall into habits where life blends one day into the next, and you’re not even really aware of the fact that you’re alive and that each day is precious. But if you are in despair, suddenly you’re very aware of the fact that you’re alive and you’re very aware of the fact that this day is today.

On a good day, I very often will look around and notice “Hey, I’m happy. I’m not anxious. I’m not feeling like the end of the world is coming. I’m not feeling like killing myself.” Part of that having-a-good-dayness is remembering what it’s like when I am depressed or when I’m having a bad day. Part of why this is a good day is because I’m not depressed.

When I’m having a bad day, to make myself feel better, if I hadn’t had some exercise scheduled, I’ll make sure there’s some exercise, ideally a walk. If I get lucky, it’ll be a sunny day — the sun is particularly helpful for me. I’ll take a little extra fish oil that day. And I probably also will try to stay away from my phone and my computer as much as I can and try to focus on smaller, more immediate tasks — like the details of the day, taking care of my children, checking in with my wife probably more often than usual.

Sometimes if I’m having a bad day, I call my eldest daughter and check in on her day and see how she’s doing. Just hearing her and talking to her gets me out of my own head.

Is this really helping or is this harming?

Now, about a year and a half ago, I went through a depressive episode that lasted a couple of months. It was one of the worst of my life — at least the worst that I recall since childhood. At that time, I just had to remember to survive the day. I would constantly turn toward the depression, welcome it, treat it like a friend, try to care for it, and remember “I don’t know what tomorrow will bring. Tomorrow, I may wake up and feel totally great. I don’t think that’s going to happen, but it could happen.”

Discovering what works best for my depression took experimentation and long practice. The German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche said that in order to flourish as a human being, you had to pay attention to the simplest little things, like what climate was better for you as opposed to worse for you, what kind of friends are better for you as opposed to worse for you, what kind of books have a good effect on you as opposed to a bad effect. He even said simple things like whether or not you should drink coffee or tea.

I think Nietzsche is exactly right about this. Each and every one of us, but particularly those of us who suffer from anxiety and depression or suicidal ideation, we have to be scrupulous about looking at our own mental well-being or lack thereof and seeing how it interacts with our environments. When it comes to every aspect of that mental well-being, including in my opinion, your prescriptions, you have to ask yourself: “Is this really helping or is this harming? I’ve given it the four weeks my psychiatrist asked for — is it making me feel better or is it making me feel worse?”

I’ve been in the psychiatric hospital quite a number of times, and if you go to the psychiatric hospital with any frequency, you’ll wind up on a lot of medications. At one time, I was on as many or as eight or nine different psychiatric medications. The process of sorting out which ones were helping me and which ones were harming me was a process of years. It took me 10 years of patient deliberation and close examination of myself to figure out which of these were helping and which ones were harming. And it was scary sometimes going off of a drug.

I have many times in my life talked to a therapist and found that if you have a good therapist, they can be hugely helpful. But finding a good therapist or a psychiatrist is a real project. I had a wonderful psychiatrist for a long time, and then she died, and I haven’t found someone like her yet.

I have a network of friends now who suffer from similar problems. And honestly, I get my therapy now from talking to them. Through people reaching out to me about their depression or after suicide attempts, I’ve inadvertently formed this group that I talk to. It’s a little community of people who all recognize we’re struggling with the same sorts of things, so it’s been very helpful to me, and it just kind of grew on its own.

Someone, something, anything, help me.

There’s only one time when I was so depressed that I couldn’t move. I’ll never forget it. This was in 2009, and I was walking home from campus — I’m a philosophy professor, and I always cross the campus of the Nelson-Atkins Museum, which is on the way home for me. I was passing this pond art installation by a sculptor I love, and my depression had been so bad that it had been really hard for the past couple weeks to move; even to lift my arm was hard. Doing anything took this incredible effort.

So I was walking past this pond, and then suddenly I realized I was too depressed to move anymore. I simply could not move. I stopped walking and I realized that I couldn’t walk. I didn’t have the power to take even one more step, and I just stood there. I didn’t know what I was going to do.

I just prayed, and I am not a believer in any theistic religion, but I said, “If there is anything in the universe, anything out there that could possibly help me, now is the time. Someone, something, anything, help me.” I just begged standing there, and this tiny beam of sunlight slipped into my head, and suddenly I could breathe and walk again. This was the turning point of that particular depressive episode.

Suicidal ideation is just part of who I am.

It’s been a long time since I’ve tried to kill myself — a few years since I’ve made a suicide attempt. I think part of that reason for that is that I’ve accepted that suicidal ideation is just part of who I am. And I don’t have to act on it. I can be so worried about my daughter and not do anything about it, other than talk to her. It’s not like I have to fly down to Austin to try to solve all her problems. Similarly, with suicidal ideation, I could be thinking about killing myself all day long, but I don’t have to do anything about it.

I don’t want to jinx myself, but in the past three years or so, my suicidal ideation has been getting more and more passive. It’s not like it’s gone away, but it’s become less and less menacing. Then, in the past few months, for the first time in my life I’ve had days go by when I didn’t think about suicide. I have had three, four, five days at a time go by when I didn’t think about the various ways that I could put an end to everything. This has been miraculous and a brand new thing.

I don’t know why this is the case, but I think it may have to do with having written this book about suicide and finally having put on the page everything that I’ve ever thought about or worried about, all the mistakes I’ve made, all of the anxiety, stresses, ways I’ve been a terrible parent, all the huge spectacular messes I’ve made of my life — looking it straight in the eye and being willing to say it out loud so that my children can read it, anyone can read it. I’m thinking that might be what did it.

I may finally have actually started to make a friend of my self-loathing, which I thought I could never make a friend of. My depression and my anxiety seem like relatively small monsters compared with my self-hatred. And maybe this book helped me make a friend of my self-hatred and realize that it doesn’t have to be something I’m fighting against. That too can be some aspect of me that I’m accepting. I might be starting to realize “Oh, this guy Clancy, he isn’t so terribly important, so don’t spend so much time worrying about him.”

If you or someone you know is experiencing suicidal thoughts, call the National Suicide Prevention Hotline at 988 or 1-800-273-8255 or text HOME to the Crisis Text Line at 741741. You can also reach out to the Trans Lifeline at 1-877-565-8860, the Trevor Lifeline at 1-866-488-7386, or to your local suicide crisis center.

This article was originally published on