Why 30-Somethings Can’t Find Happiness (Or Money Or Sleep Or Friends)

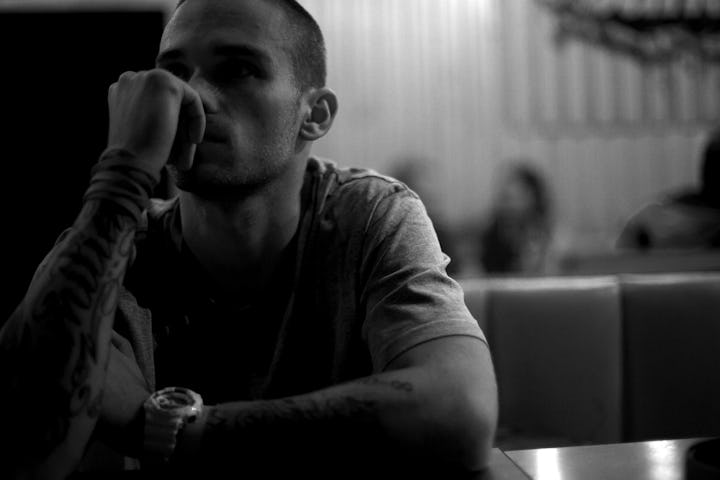

One question defines Americans' third decade: Why am I so sad?

Jordan Teitelbaum is a successful guy. Also, busy. At 32, the father of two is finishing an endoscopic sinus surgery fellowship (he specializes in removing brain tumors through the nose), looking for a job, paying the mortgage on his new house, and trying to be present in the life of the woman he married three years ago while attempting, in the spare moments he doesn’t really have, to look ahead.

“I’m only partially into my 30s, I can see that this will be the most demanding decade yet,” he laughs. “I’m trying to set up the rest of my life, not just for myself, but for my little family.”

Teitelbaum doesn’t sleep much. And he’s far from alone. Doctors or not — hell, parents or not — American 30-somethings tend to struggle with the stress of their third decade after the comedown from their mid-20s before stabilizing in their 40s, lightening up in their 50s, and peaking again in their 60s. (Research shows that happiness peaks at the age of 23 and 69, hold the jokes.) The ennui takes many 30-somethings by surprise — they tend to be, after all, more secure and stable professionally, personally and financially than 20-somethings — but maybe it shouldn’t. In 1968, ur-developmental psychologist Erik Erikson posited that there are eight stages of psychosocial development and that the sixth stage, “Intimacy vs. Isolation,” occurs between the ages of 18 and 40. This stage is characterized by significant emotional conflict in close relationships. If the stage is completed, people move on to have healthy, secure, and committed relationships. If not, they struggle to move on with their lives and face a heightened risk of loneliness and depression in the long term. In other words, 30-somethings like Teitelbaum are playing a high-stakes game.

No wonder they’re so stressed.

Regardless of lifestyle, personal well-being tends to bottom out in people’s 30s. Why? Because as 30-somethings shed the impractical expectations they carried through their 20s, age, economic realities, and social changes deliver a combination punch that, emotionally speaking, puts many on their ass. And, yes, it’s worse for parents. There’s reason to believe that the early parenthood drives down well-being scores significantly. As rewarding as parenthood may be in the long-term, the short term is hard as hell.

What can people in their 30s do other than white knuckle it through the toughest time of their lives?

“Before we hit our 30s it’s acceptable to make mistakes both professionally and romantically. But as we get older, failure may feel more significant and lead to some loneliness and isolation,” Karen Rosen, a psychotherapist and clinical social worker, explains. “Combine this with the strain of sustaining a household and you have some adults who are really tapped out. It’s a time of pretty strained resources.”

There are plenty of economic factors that exacerbate 30-somethings’ economic concerns. Financial experts recently estimated that the age of 31 is the most expensive year of people’s lives on average, costing people about $61,000. This is a consequence of a combination of big bills, such as weddings, buying a house, having a baby, and paying for a honeymoon, on top of everyday expenses, but does not include retirement savings or money to support a family in the long-term — that will cost extra.

Because of tiredness and feelings of abandonment, 30-somethings focus bad energy on themselves. And all that self-reflection can exacerbate the problems.

That means that, with the average salary hovering just over $44,000 among full-time employees, plenty of people spend their third decade going into debt. This is more the case now than historically because of the outsized effect of the Great Recession on Millennials. Americans born between 1981 and 1996 have fallen short of every generation of young adults born after the Great Depression, amassing less wealth than their parents and grandparents despite higher levels of education. Men and women in their 30s are marrying at the lowest rates on record, and the U.S. birth rate is similarly the lowest it has been in 32 years.

Though the job market has recovered since cratering in 2008, Millennials remain behind when it comes to earning, wages adjusted seemingly forever down after entering a job market at cut-rate salaries, and that’s on top of decades of wage stagnation. It doesn’t help that student debt has exploded. The average debt after graduation is about currently $30,000, nearly double what it was in the 1990s.

The not-so-great good news for Millennials is that many owe less because they have fewer assets. In 2021, homeownership rates fell to 38 percent among people under 35, compared to nearly half of Baby Boomers who owned homes at the same age. This has inevitably driven down home ownership rates overall to the lowest in half a century, 63 percent, compared to nearly 70 percent in 2005, when the subprime lending bubble was about to burst. The problem is not that Millennials are unmotivated or unaware of their generational shortcomings. Research out of Stanford found that most people over 25 actually want to get married by the age of 27, buy a home by 28, and start at family by their 29th birthdays. But since the ability to accomplish these goals has decreased with every generation, those between the ages of 25 and 34 want them the most. But thanks to the rise of the gig economy and false promises of hustle culture, they are the least set up to achieve them.

And here’s the thing: 30-somethings would be feeling the burn even if none of those things was true. Why? Because 30-somethings are in a high resource demand part of their lives. They are, on average, supporting a kid, making car payments, and trying to invest or investing in real estate. They are also incurring the costs of working (commuting isn’t free) while also spending on activities designed to help them maintain social connections that seem increasingly tenuous. If weddings make peoples’ 20s expensive, everything makes peoples’ 30s expensive. This is a lesson people tend to learn in the 50s, when they report being about five to six percent happier than those in their 30s in no small part because they’ve made it to a lower-demand, higher-resource point in their lives.

Every day is a marathon...Drained is a good word for it.

There’s a reason why grandparents often seem so much happier than new parents. They have money.

They also have kids. That might sound odd, but there’s a difference between having young children and having grown kids. Research suggests that having grown kids increases well-being profoundly and that having young children does not. Individuals who invest the struggle that is their 30s into having children, like Teitelbaum, generally experience higher levels of happiness in their 50s, whereas those who do not either flatline or become worse off.

A recent study of over 55,000 people 50 and older demonstrated this, along with other work published in 2011 and 1994. Parents are not invariably happy, but they become happier once children achieve economic independence and move out. This is presumably because grown kids provide social and emotional support and keep their parents engaged in a way that infants can not and do not, forcing their parents to look for meaningful connection elsewhere.

And that search, as many can attest, becomes hard after the party-hardy 20s come to an end. A study of over three million men and women found that the number of friendships they had started to decline in their mid-20s, dropped off dramatically throughout their 30s, and did not begin to rebound again until their mid-40s, when their kids were older and more self-sufficient. The problem? Thirty-somethings just don’t have the bandwidth to maintain many close relationships and lose touch with the outside world as a result. And this takes a massive toll. Friendship has been found to lower blood pressure and BMI, increased longevity, improved psychological health, and increase individuals’ ability to cope with rejection. For 30-somethings, this is particularly dangerous. Consider Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. It’s called a hierarchy for a reason: If people cannot elevate themselves to a point where they feel a sense of belonging, they will not be able to elevate themselves further and get a sense of self-esteem. This makes the inevitable diaspora of the 30s — friends moving for work, love, and to have children — profoundly destabilizing on a personal level.

“Our basic needs such as food, sleep, shelter, and safety are the staples of our well-being. Lack in any of this can, in the long run, have detrimental effects on our health,” Dr. Lina Velikova, a physician and sleep expert. When those needs are not met, it is that much harder for people to experience deeper feelings of fulfillment.

It’s also worth dwelling on that second need for a moment because sleep and sleep related issues define, in many senses, the experience of living through one’s 30s.

Sleep starts to naturally decline in sleep that starts at the age of 30, exacerbating mental and emotional strain. Deep sleep specifically, also known as delta sleep, which supports memory and learning as well as facilitates hormone production, declines by some 50 percent by the time people enter their 30s. A massive review of literature published in 2017 found that this may be a result of aging brains fail to recognize signals of tiredness or exhaustion. The result is usually a combination of insomnia and sleepiness, the haze of early middle age. Parents, who lose an average 109 minutes of sleep every night for the first year of their children’s lives, struggle more.

People who sleep less than the recommended seven-hour minimum produce more stress hormones like cortisol, experience more inflammation, and are at a higher risk for certain types of cancers. Sleep deprivation can also lead to sexual dysfunction. Because 30-somethings are often unaware of a biological transition taking place, they may misdiagnose symptoms of sleeplessness as signs of true sexual dysfunction, mood disorders, or even burnout.

Long story short, because of tiredness and feelings of abandonment, 30-somethings focus bad energy on themselves. And all that self-reflection can exacerbate the problems.

“In America, psychoanalysis really took off because it spoke to consumerism, it spoke to privileging the individual over the collective or community, and spoke to the inward, almost egotistically if overdone self-reflection,” psychotherapist Michael Aaron explains.

The American wellness industry, broadcasting messages about hustling, seizing the day, getting perfect skin, meditating, and eating the right CBD vitamins, offers, at best, half-measures.

The problem is that individualism rarely makes anyone feel better. An overwhelming amount of evidence suggests that, for better or worse, immediate resources and environment move the needle the most when it comes to overall well-being. Immediate resources, thanks to increased spending, and environment, thanks to social shifts, are the two places that 30-somethings tend to feel like they’re losing ground. Does therapy solve that? Only if therapy promotes social behaviors and only if it helps dad and mom find time to see friends. Pre-modern man didn’t have these problems.

Aaron cites French sociologist Émile Durkheim’s seminal 1897 work, Suicide, in which Durkheim demonstrates a strong link between industrialization and suicide rates. He concludes that capitalism makes it harder for individuals to meet their basic needs while maintaining close interpersonal relationships.

“People were feeling atomized, and less of a sense of community, and feeling more alone and isolated. In losing their sense of community, they were more likely to experience depression that could lead to suicide,” Aaron explains. “Durkheim’s point is that we cannot minimize the role of the broader society in the way it affects people.”

The American wellness industry, broadcasting messages about hustling, seizing the day, getting perfect skin, meditating, and eating the right CBD vitamins, offers, at best, half-measures. Rather than being empowered to solve problems by thinking socially, Americans are pushed towards consumer solutions. It is remarkable how many of those solutions are sold — at considerable cost — to people in their 30s.

So what can people in their 30s do other than white knuckle it through the toughest time of their lives? Making more of an effort to address basic social and emotional needs is obvious, but may not be practical for everyone. Time is short (especially for parents). But sleeping more, participating in active financial planning, and asking for help are all good ideas. And, as with all things, expectations are key — and, research proves, strongly correlated with happiness and well-being. Thirty-somethings who expect to be crushing it, likely won’t. Those who understand that they may have to sacrifice short-term well-being for long-term stability, on the other hand, will likely make it through unscathed.

“Every day is a marathon, but I am happy precisely because I have two great kids, a talented and takes-care-of-most-things wife who is the dopest mom, and I am doing well in my career,” says Teitelbaum. He pauses for a second to consider his success. “Drained is a good word for it,” he adds.

Teitelbaum claims he is happy. And that’s critical. Happiness and well-being are different. While happiness is considered a temporary state or feeling, well-being is a more permanent stasis based on health, happiness, welfare, and prosperity. If well-being is the meal, then happiness is the butter. The good news is that happiness is not off the table for people in their 30s, especially parents of young children, and represents one area where they can gain traction. It may be a few years before you can get a full night’s sleep, workout, eat right, or hang out with your buddies regularly, but it is possible to be content and proud of the hard work getting done.

This article was originally published on