What Do We Make of Anti-Vaxxers In the Time of Coronavirus?

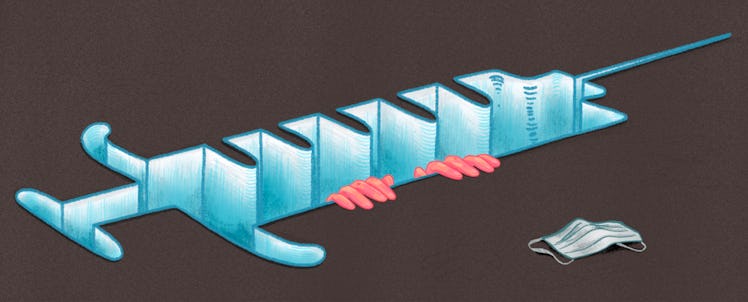

We're hoping scientists and medical personnel can pull us from the wreckage of a global pandemic. Will anti-vaxxers stand in our way?

Perhaps at no point in recent memory has America been so fluent — or at least reliant — on science. To understand R0 values, aerosolization, comorbidities, and antivirals in the news one needs to have a passing familiarity with virology, epidemiology, and, yes, vaccinology. With this familiarity comes the expected spike in public trust for doctors, health leaders, and healthcare workers. What they do is wildly complex! Also, it truly saves lives!

But what of trust in vaccinations? Going into the pandemic, confidence in vaccinations was high — 77 percent of people polled in a 2018 U.S. survey approved of them. But still, the number was not as high as most medical experts would like and had slipped some 8 percent in the past decade. With so much riding on a vaccine to end a pandemic (even if it’s still a year out), will this trajectory reverse?

On the surface, it seems so. Doctors say they’re seeing an upswing in vaccine confidence in their practices as well. “There’s a renewed awareness of how important vaccines are,” says Jay W. Lee, MD, a family physician in Huntington Beach, California. “COVID-19 is showing us exactly what a world without vaccines looks like.”

But the most ardent and vocal in the anti-vaccine community are holding their ground. On social media and publicly these groups are already vowing to never get a COVID-19 vaccine. They also claim that rather than harming it, COVID is actually a booster for their cause — because some fear a vaccine might be rushed to market before it’s thoroughly tested, people on the fence in the vaccine debate seem more open to the anti-vaccine message than ever, they say.

“To say that they’re suspicious of a potential vaccine would be an understatement. A lot believe that this is finally the moment we put microchips in vaccines to track people and usher in the new world order.”

Experts say there are many reasons why — even as the death toll of COVID-19 surpasses 73,000 in the U.S. at the time of this writing — the most staunch vaccine resisters are sticking to their guns. One of the unfortunate ironies is that the more effective social distancing efforts and city lockdowns are in slowing the virus’s spread, the easier it is to deny that COVID-19 is a threat.

Furthermore, something as widespread as COVID-19 is hard to wrap the mind around. “In pandemics, if you don’t know someone directly impacted, it might be hard to visualize the impacts, and therefore the threat seems less real,” says Sarah E. DeYoung, Ph.D., an assistant professor of sociology and criminal justice at the University of Delaware who has studied vaccine resistance. “The problem with COVID-19, measles and other outbreaks is that they are like a ‘blue skies warning’ during hurricane season: It’s more difficult to convince beachgoers to evacuate three days before the landfall of a major hurricane because everything seems fine.”

Some of those who watch the anti-vaccine movement closest agree that the fight against the most trenchant anti-vaxxers is a lost cause. “To say that they’re suspicious of a potential vaccine would be an understatement,” says Cassie, a pro-vaccine mole who until recently was a member of a large anti-vax group in order to keep tabs on the movement. “A lot believe that this is finally the moment we put microchips in vaccines to track people and usher in the new world order. They firmly believe that if the virus is real, everyone needs to build up immunity naturally.”

So therein lies, to the surprise of few, the views of the hardcore anti-vaxxers. But what of the vaccine-hesitant? This group is itself a sizable one and, importantly, one that can be swayed in either direction. These are parents who aren’t sure it’s safe for their babies to get so many shots at once, for example, or they know someone whose kid had a bad reaction to a vaccine and are now leery.

Take Daria, a mother of two in Irvine, California, who vaccinated her kids so they could attend preschool but spaced their shots out as much as possible. No one in her family gets flu shots. She says she’s fine with some recommended vaccines because she knows they’re important but feels like there are too many of them. Her first son got a rash on his legs after every round of shots.

When she couldn’t sleep, Daria says she’d research vaccine information online and that the hours of reading did little to allay her fears. “There’s no hard yes or no about vaccine safety,” she says. “And you can’t sue vaccine makers, so if something goes wrong, what do I do?”

“The anti-vax movement is well-funded and organized and attacks the idea of vaccines from multiple angles. While we idiots think,’I’ll publish another paper and just show the results.’ We’re not combatting it on the right front.”

Like Daria, a lot of parents in the middle of the vaccine debate feel alienated by both anti-vaxxers and pro-vaccine parents. Express fears about vaccines, and some parents peg you as an anti-vax nutjob, Daria says, while anti-vaxxers would castigate her for vaccinating her children at all. This isolated position in the debate makes them more vulnerable to anti-vaccine messaging which might be more persuasive than you think: The most negative anti-vaccine messaging was 500 percent more effective than pro-vaccine messages, according to recent research from anthropologist Heidi Larson, director of the UK nonprofit The Vaccine Confidence Project, cited in a TED Talk.

Although they’re a small segment of the population, anti-vaxxers are masters at persuasive messaging. This is because they’re agile, they respond quickly to social media, and adapt messages rapidly to what the market demands, says Robert Bird, a professor of business law at the University of Connecticut who has studied the anti-vax movement

A lot of this messaging hinges on false information. The most extreme version of this comes in conspiracy theories. Anti-vax groups on Facebook and Reddit are plagued with posters insisting that Bill Gates is a baby-killing monster who created the COVID-19 virus in order to implant tracking devices in people, that the virus is caused by close proximity to 5G cell towers, and other posters who say the virus is a hoax and death tolls have been wildly exaggerated by the government and the media.

To most, these are on their face ridiculous. But then there are more subtle messages that, while just as baseless, may reach that vulnerable vaccine-hesitant population. Among those who at least believe the virus is real, there are more insidious claims that the only people dying from COVID had weakened immune systems from this year’s flu shot. They also say that because most people recover from COVID-19, it proves their point that a vaccine is unnecessary as long as we have healthy immune systems.

“If you have a movement that’s not hinged to facts, it’s easy to be agile,” says Bird. “An absolutist message that can morph and change to the needs of the audience, and is repeated again and again, retains a certain power.”

Scientists are trained to hypothesize with caution and to only reach conclusions when the evidence demands it, he continues: “Whereas the anti-vax movement is relatively free from those restraints and can bring a simple, compelling and repetitive message that can strike at people’s hearts.”

The pro-science contingent isn’t blameless, says David Cennimo, MD, assistant professor of medicine-pediatrics infectious disease at Rutgers University. “The anti-vax movement is well-funded and organized and attacks the idea of vaccines from multiple angles. While we idiots think,’I’ll publish another paper and just show the results.’ We’re not combatting it on the right front.”

So what is the right front? What’s a public health messenger, one who hopes to hinge the safety of Americans on an eventual COVID-19 vaccine to do?

“A problem in our field is that we automatically get our guard up and think we’re talking to Jenny McCarthy every time we get a question about vaccines.”

To start, experts suggest we all stop alienating the vaccine-hesitant. Referring to them as “anti-vaxxers” only steepens the divide and bolsters an “us vs. them” mentality, says Shane Owens, a psychologist in Commack, New York. That’s the first point he says he plans to make in a presentation addressing vaccine resistance at the American Academy of Pediatrics in October. Also helpful would be for celebrities and influencers to normalize vaccinations by talking about getting vaccines for their kids as a healthy choice, for example, he says.

“People don’t see many celebrities saying how important and necessary vaccines are, but there are many of them who make the case that vaccinations are bad or, at least, unnecessary,” Owens says.

Instilling greater trust in doctors and the government would be more effective than making scientific arguments to vaccinate for the good of society, he says. And doctors should be more patient about answering the questions of vaccine-hesitant parents.

“A problem in our field is that we automatically get our guard up and think we’re talking to Jenny McCarthy every time we get a question about vaccines,” Cennimo says. Doctors should ask what parents’ specific concerns are, such as whether it’s a particular vaccine they’re unsure about or they’re worried that too many shots at once might harm their child.

Advertising that could effectively communicate the benefits of vaccines should include wording that personalizes the message, DeYoung says, offering as an example, “You make sure your child wears a seatbelt. You put sunscreen on her. You keep them safe from strangers. Protect her and her friends from deadly illnesses.”

“When people see numbers and statistics, that may not speak to them on an emotional level,” DeYoung says.

An emotional component is essential, Bird agrees: “And it needs to appeal to people’s sense of health and well being.” As we’re quarantined in our homes, facing a pandemic unprecedented in our lifetime, fearful for the elderly, our jobs, and looking for a science-backed way out of this, the appeal is there. We just need the right messengers.