Growing Up Fast On Planet Earth, With Kim Stanley Robinson

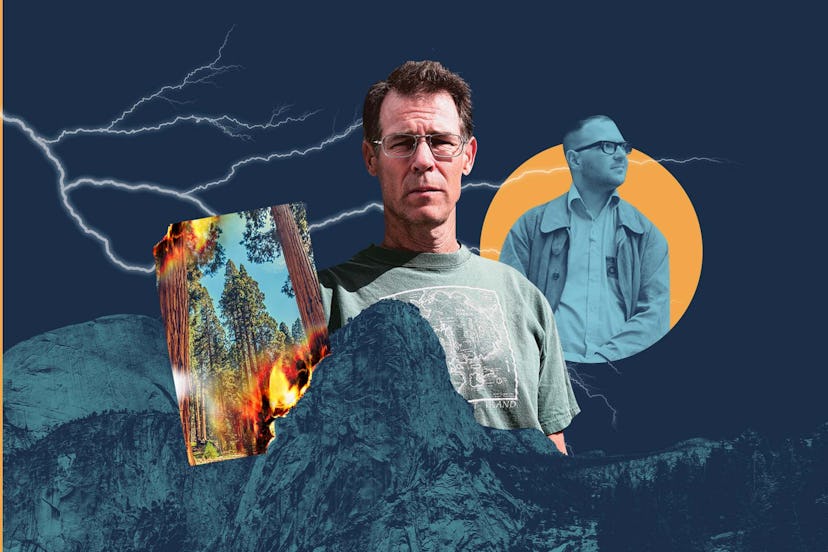

The peerless Kim Stanley Robinson talks with Cory Doctorow about climate change, the moral necessity of hope, and helping kids feel deeply connected to the natural world.

Kim Stanley Robinson is having a moment. This is a funny thing to say when you look at his credentials. Robinson has a storied career as a sci-fi author with 22 novels under his belt and as many big books awards (including Robert A. Heinlein and Arthur C. Clark awards for his body of work). But his latest novel, an equal parts hopeful, harrowing, and informative climate change tome, The Ministry for the Future, has struck such an immediate nerve that Robinson has found himself speaking at the United Nations Climate Change Conference in Glasgow, chatting with the Dalai Lama, giving TED talks, and interviewing for the New York Times and the New Yorker for big printed profiles about his life and thoughts. He’s moved from a man with big, brilliant, often utopic ideas about Mars and the future and hero scientists to someone world leaders might look to for advice when shaping climate policies that could change the course of human history.

So what kind of advice might he have for those of us living on this increasingly imperiled planet? What are we to make of his advice when we’re raising kids through very real floods, droughts, wildfires, and storms that are unprecedented in human history? There are clues to this in Robinson’s latest release, The High Sierra: A Love Story, a memoir about the place in the natural world that he has gone back to over and over again throughout his life — to hike, camp, explore, and think.

Fellow science fiction writer Cory Doctorow — who has been friends with Robinson (“Stan” to those close to him) since 1993 — sat down with the author to discuss just this. Doctorow is a true peer to Robinson, with 18 novels and collections to his name, not to mention dozens of (brilliant) short stories and his share of writing awards. The two authors are some of the biggest thinkers of our time when it comes to the world as it is, might be, and could be. So when they sit down and discuss questions like “What does thinking about the future actually mean to parents and citizens of a changing planet?” and “How can we hold onto hope?” they come by their answers honestly.

Doctorow thinks that Robinson’s two books — The High Sierra: A Love Story and The Ministry for the Future — could be the capstones of a profoundly influential and successful career. But, the stakes for us all are much higher. Climate change isn’t science fiction after all; it’s happening to the world we live in. And, Robinson thinks, we can all become great stewards of our world if we only pay close attention to it and teach our kids to do the same. –Tyghe Trimble, Editor-in-Chief, Fatherly

Cory Doctorow: Both The High Sierra and The Ministry for the Future are about the climate emergency and nature. What would you say to kids about nature and the emergency?

Kim Stanley Robinson: You can tell kids, “50% of the DNA inside your body is not human DNA.” You yourself are a forest. You are an amazing collaboration between literally millions of individuals and thousands of species. That’s so strange that it might take some getting used to, but it's good to know the truth, and it is true.

If you can understand all that, you might think, “Well, that’s that swamp, that there aren’t very many swamps left. That hill that is wild at the edge of town, that’s part of my body. If we tear it apart, we're tearing apart, like my foot, and then I’m harmed.”

The sense of connection between our bodies and our world needs to be enhanced — especially for modern kids who are very often Internet-ed, looking at their screens. Screens are all very well, that urge to communicate. But the planet around you, the landscape, is part of your body that needs to stay healthy. I would start with that and go on from there.

CD: Ministry for the Future touches upon this idea of connection. It speaks to the need for humans to work together and finds hope where they do — not a fatalistic optimism that things will just be fine, but the belief that if we push hard and alter our circumstances a little, we might attain a vantage from which we can ascend further. What brings you hope?

KSR: Well, the situation is dire, and I mean the climate crisis, the polycrisis, the climate emergency, the way of people. We’re very close to breaking some planetary boundaries of biophysical cycling. If we break them, it is beyond the powers of human beings and any technology we can conceive of to claw our way back. In that case, civilization is in terrible trouble and everywhere will look like Ukraine.

To talk about “hope” is to perhaps be trying to talk about resolve. Hope is a moral necessity amongst the privileged in the developed nations to work our butts off while we can because we won’t be the ones taking the hit first if we don’t act, but, eventually, it’ll get to us too.

You yourself are a forest. You are an amazing collaboration between literally millions of individuals and thousands of species.

I’m really lucky. I inherited my mom’s biochemistry. She was a cheerful and positive person, but she also had to choose to do it when times were hard. I learned a lot from her, and my native sensibilities are like, “Well, let’s go garden. Things are going to work out.” It’s a lucky thing.

But then, as a political choice, you have to say, “Whatever can be done must be done — and the sooner the better.” If we were to do everything right, it would still be really messy, but we could dodge the mass extinction event. We could get to a better place.

That’s why people are responding to Ministry so fervently. It’s utopian — if you put the lowest bar possible on utopia. It supposes we might dodge a mass extinction event over the next 30 years. That is utopian compared to the other stories that are quite possible.

CD: When you wrote The High Sierra: A Love Affair, you say you were worried you’d regret not having written if you keeled over with a heart attack. It’s a memoir, a natural history, a guidebook, and even a bit of a polemic. It’s got all these different moving pieces, and all these different modes. How did this book come together?

KSR: Memoir is an odd thing. You are making it up. You are summarizing vast amounts of material into just one small string of sentences and judging your younger self in ways that are possibly inappropriate, but your younger self is not around to yell at you.

I was a suburban kid, a bookish kid. It was boring. My town was a white bread, scrubbed-of-all-traces-of-personality place. Orange County was Southern California suburbs at their most dull.

But I had the beach. I’d get into the ocean, get 20 yards offshore, and Mother Nature would try to kill me, and I was in a wild adventure. I was in a wildness and danger and swimming my brains out and loving out, and I’d look back at this Mediterranean civilization, the line of houses at Newport Beach. The beach was my salvation.

Then I went to the Sierras as an undergraduate. I was 21 years old. A friend took me up there. We took LSD. I joke that I never came down from that day.

In the Sierras that day, I had this impression of vast vastness, beauty, significance. There was some kind of meaning I couldn’t grasp — the meaning of being up there in the Sierras. I began to go to the Sierras a lot. The rest of my life, including my life as a science fiction writer, has been ... How can you say it? Has been platformed by this wilderness experience. I was oriented in that experience, and I never lost that orientation but just developed out of that.

CD: I’m thinking of my own kid. She’s 14 now. She's been locked indoors because of the pandemic, and it’s become a habit. She wants to be on screens with her friends in her bedroom with the door closed. The great outdoors are a little scary and uncomfortable for her. How can a parent approach the High Sierras or other wild places?

KSR: Scale the trip to the strength of the person you’re taking so that they don’t experience it as suffering and renunciation — allow them to be comfortable. At that age, they’ll actually be quite strong. Even if they sit all day, every day, they will have native strengths that will come into play.

I started taking my kids up into the Sierra when they were 2 and carried them a lot of the way. If you have kids that young, carry them and let them trip around the campsites but not have to get into a mode of suffering, because then they won’t like it the rest of their lives.

They could wander around and make up games, really simple ones like throwing rocks at a tree on the other side of the lake. They aren’t being driven to do something but let free.

Car camping is the worst of both worlds. You’re still trying to do what you would do at home — but badly, because you’re in the back of your car. You're not quite in wilderness — you’re in kind of a little tenement of other people in other cars nearby. Where’s the attraction to that?

In the Sierras, I would go to Desolation Wilderness. Everything there feels quite high, quiet, stony, quite glorious, but really small scale and also a little bit lower altitude.

In Desolation, we used to go to a place called Wrights Lake. You have to get a wilderness permit, so there won’t be too many people there. You’ll hike 2 miles in; you’ve gone up 800 vertical feet.

It can take all day with little kids. You get up there, you’re in one of the most beautiful Sierra granite spots ever, glaciated and glorious, and then you just... let them loose.

In my time they would bring up little handheld electronic games. But they themselves would get bored with that after an hour because they could wander around and make up games, really simple ones like throwing rocks at a tree on the other side of the lake. It gets basic and quickly you get to the outdoors-ness, the beauty of it and the relaxation. They aren’t being driven to do something but let free.

Most kids are channelized by their parents, especially us in the bourgeois middle class, where their lives are choreographed for them. The idea is to say, “OK, OK, we’re in camp, we’ve hiked a mile, it’s a different camp site. We’ll set up the tents, you go play.”

They’re in a different landscape after like an hour’s work. The whole rest of the day stretches out. At first, it can even be disorienting. You know, like, “What do I do with myself?” After a while they begin to think, “Wow, let’s go see that.” Or, “What if a deer shows up?” which sometimes they do. Marmots are very common.

In other words, keep it small.

Embrace the lightweight movement where you do not have to put tens of pounds on your back. Modern tech allows you to go up there with an extraordinarily lightweight kit, which I have a long chapter on, probably too long. [Editor’s note: Don’t listen to him; this is one of the best chapters in the book. -CD]

Take them up, make it a four-day trip so they see the end of it. On the fourth day, they’re going to be thinking, “D*mn, I could’ve used a couple more days.”

CD: You make me regret not doing this with mine when she was smaller. What would you do with older kids, teens, who you can’t just drag out to the woods and set loose?

KSR: I suggest buddying up so they have a friend and then maybe you have another couple. That’s how I did it. There’s a chapter where I describe a group who met because our kids were in the same preschool. We’d go up together, set up camp, and then just let people loose.

No expectations, no plans. It was like, “OK, I’m going to walk up Peak 9441. If you want to come, come; if you don’t want to come, don’t come.” The kids immediately split into what one of our day care workers called “monkeys” and “pumpkins.”

We have a lot of problems with kids who are poorly suited to sitting in chairs for the bulk of every day. It’s basically crowd control. It’s day care. It’s preparing you for life at a desk.

The pumpkins will sit in camp, and they’ll talk and they’ll have a blast talking. The monkeys will go, “Give me that peak, man. I don’t get enough of this in life.” They’re the kids that are sitting in classes every day going, “What the hell is this life about? Why am I forced to sit here when I am a monkey and I want to run up a jungle gym or get in a fight?”

We have a lot of problems with kids who are poorly suited to sitting in chairs for the bulk of every day. It’s basically crowd control. It’s day care. It’s preparing you for life at a desk.

There’s aspects of schooling that are nightmarish to contemplate, especially if you’re a parent. You look at what’s happening, you go, “Godd*mn it. I probably should have homesteaded in Alaska.”

CD: The High Sierra is a book about how the Sierras changed your life, how you went up and never came down. How did it change your life?

KSR: It’s not straightforward. I keep a garden. I grow vegetables and, therefore, I live in fear because I know that we’re not even in control of our food supplies.

I began working outdoors. I put up a tarp, so I had shade on my laptop. The first time it rained, the tarp kept the rain off. All of my novels in the last 16 years have been written 100% outside.

The heat is hard, but the cold is not, and you can work in the rain too, and it’s quite glorious. For three or four novels in a row, my last day of work coincided with bizarre storms, and I was thinking that it was nature’s way of going out with a flourish.

I came home and I realized that it’s best to spend more time outdoors than we do. There’s a lot of people who know it’s fun to be outdoors because they’re carpenters and they’re outdoors all the time, and they like it. Farmers too. But writers, not so much. So a garden, working outdoors and then being an activist for environmentalist causes, greening everything in my life and my political aspirations of looking for what would be best for the biosphere.

Aldo Leopold said, “What's good is what’s good for the land.” It’s a deep moral orientation — like a compass north — but the land, the biosphere, goes from the bottom of the ocean as high in the air as living things. Think about the land not as just dead mineral sand but as soil. It’s alive. So “what's good is what’s good for the land” becomes a rubric you can follow all over the place.

All my stories tell this story. You’re not surprised by these things that I’m saying because that’s what I actually write about too and see if I can spread the word.

This article was originally published on