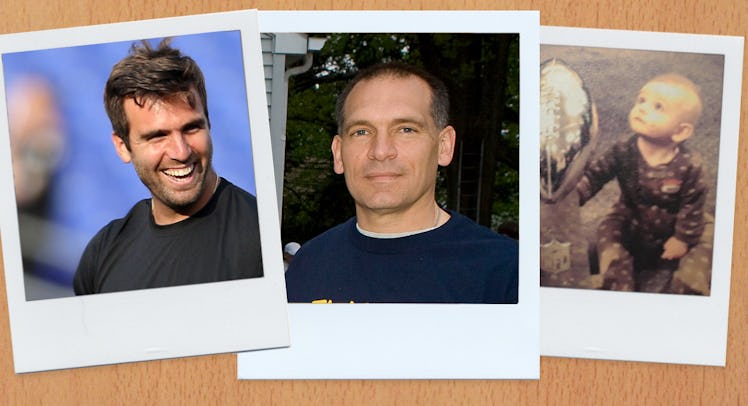

How to Raise an NFL Player: A Conversation with Steve Flacco

Baltimore Ravens QB Joe Flacco has seen it all as an NFL quarterback, and his dad, Steve, has been there with him every step of the way.

For the 2017-18 NFL season, Gillette is partnering with select fathers of NFL players and Fatherly to celebrate the proud moment when a player steps onto the professional football field for the first time, and the hard work and dedication required of their families. Because the big days in a child’s life are big days for the countless people who have stood beside and behind them. Through “His Big Day” Gillette is reminding all of us that no one accomplishes great things alone and, when greatness is achieved, it’s a proud moment for everyone who’s helped along the way.

Joe Flacco has seen it all as an NFL quarterback, and his dad, Steve, has been there with him every step of the way. The tall, cannon-armed Flacco started all 16 games (plus the playoffs) for the Baltimore Ravens as a 23-year-old rookie in 2008 and reached the pinnacle of football when he was named MVP of Super Bowl XLVII. In his 10 seasons, he’s also been questioned and doubted at every turn (it goes with the position). How does he keep such a level head? Plenty of credit goes to his dad. “We were close. We were always honest with each other. He told me when I played well and when I was terrible,” Joe Flacco told the Baltimore Sun. Steve Flacco saw a pro in the making when his son sprouted to 6-foot-6 (he is 5′ 11″), and helped him on his way by being hands-on: making sure he didn’t burn out on football too young, setting up extra instruction at home, and providing constant feedback.

When did you first realize Joe was so talented?

You know, all of our kids were pretty good at ball games growing up, and they all played baseball much earlier than football. I would say pretty early on I realized Joe could throw things, particularly a baseball. We had hoped he would grow up and play baseball in high school — though we also knew he was going to play football. By the time he got to high school we realized he was special in the way he threw a baseball and football. And he was a little unusual … my wife’s about 5’ 6” and I’m 5’ 11”. He outgrew me in eighth grade — and I’m one of the taller people in my family. When he outgrew me in eighth grade, and by the time he was a freshman he was like 6’ 2”, then he was 6’ 3”, and he was 6’ 4”, and we’re like, “Wow, he’s going to have size.” So at that point, you start realizing he’s going to play something after high school.

“I would say pretty early on I realized Joe could throw things, particularly a baseball.”

How did you develop him for football?

We didn’t. He was so busy playing football, baseball, and basketball all year, we didn’t do any of the camps. I probably missed the boat, didn’t realize really what was going on around the country and all these kids are going to camps all summer. We tried to take the summer off. We didn’t even play that much baseball in the summer because they were always practicing everything that I felt like they needed downtime, particularly with his arm.

“By the time he got to high school we realized he was special in the way he threw a baseball and football.”

What were your emotions for Joe’s first big moment in the NFL, playing on Week 1 as a rookie?

As a parent … c’mon, you’re living the dream! I think he was probably a year older than most kids because he played five years of college, but what, he was 23? You’re at the top at that age. And that’s what’s impressive: You’re the best at what you do in the world at 23 years old. You could argue you’re the 31st best, but still, you’re the best.

You have to understand, this happens overnight. I spent a lot of time in the car with Joe. That was one of the benefits of being at Delaware, I would see him more often; when he was at Pitt, I wouldn’t see him. I’d go, “Look, these are the last couple months you and I are going to have this kind of time together, you can talk about all the things that are good and things that are bad and things you need to hope to go better.” Because you’re in the boat together. It’s good in that respect.

What came to mind when you thought about your son playing in his first NFL game?

When we showed up on Week 1 and he was playing already, I knew Joe was going to be fine. I thought, ‘Hey, what’s it going to be like? What’s it going to look when he gets on the field?’ Look, you quickly adjust to the point where you’re thinking, ‘OK, he better be good.’ You change gears very quickly. No one gets to that place by being the kind of person who isn’t critical of himself.

Do you think Joe knew how powerful of a moment his first NFL game, “his big day,” was for you?

I’m sure if he thought about it, but his head was probably so full of everything else that it was the last thing he was thinking about. Joe knew he didn’t need to worry about us. He knew we would be at the game and know how preoccupied he was. But it was all good. There’s still a euphoria around him being a pro. It’s still exciting to go sit in the stands.

Was there stress mixed with that “dream” feeling?

Yeah, a lot of anxiety. A good example is when Joe was a senior at Delaware and we didn’t know where he’s going or if he was going anywhere. People would invite me and my wife to the pregame stuff and she’s like, “Ugh, I can’t do it. I’m going to show up at game time, I get in the stands, I’m nervous enough as it is, it’s hard for me to relax, you don’t want me at your tailgate party.” I’m worried about how well he’s going to play — which is taken to the next level, because he’s a quarterback. If your son’s playing other positions, you have to literally watch them to figure out what’s going on. You still want the same things for them, it’s just not going to be as public if they fail.

So you were teaching him how to deal with pressure?

Football’s an emotional game — and it requires intellectual and emotional control. It’s one of the biggest things for these kids. I don’t think people understand when they recruit these kids what’s going on inside their head. And I’m not talking about the playbook. There’s a lot of pressure and stress on these guys that come from a lot of different angles. And how all that’s affecting them can really undermine all the good things you’re trying to do with them with the on-field stuff. And I don’t think people fully understand — and I say that because I’ve been close enough to it with him to have learned a lot about what it takes to keep moving down the road. How much mental energy they burn during the course of the season, that’s always as important. That’s if you want to last into the playoffs. There’s a certain amount of energy that gets burnt, mental energy, you want to conserve that as well as your physical.

Since, as you said, Joe didn’t have as much formal football training as others, how did you teach him and develop him yourself?

Since nobody ever taught him how to read a defense or anything like that, we would have to watch film on our own. We would film all our games ourselves and go back and he learned where to throw the ball, the velocity, the right velocity, the right timing, very very consistently through high school. When you get to college it’s just a matter of, “Hey, I need to learn the offense, I need to know where people are so I don’t have to think about where I’m going with the ball. I can react to what’s going on around me without thinking about it.” He understood those things.

Do you consider yourself Joe’s biggest fan?

I don’t know if I really consider myself a fan. I mean certainly people in our family are. But it’s not about being a fan. I’ll tell you I like who Joe is, and he’s exactly who we raised him to be. Some people don’t like the way he is, especially with his show of emotion. Well, we raised him to not let anybody see you sweat. And I would tell them, we like the way he is and I wouldn’t change much about it.

Do you have a proudest moment from his 10 years in the NFL?

It’s not a pride thing, but winning the Super Bowl. If you’re a quarterback in the NFL, you are judged by Super Bowls. And the funny thing is they’re the most dependent guys on the team, dependent on everybody around them. “Oh, he carried the team on his back!” That’s bull. They carried him. That’s the reality of it. If you’re not good up front, on both sides of the ball, you’re probably not going to be good regardless of the quarterback, no matter how good he is. But winning the Super Bowl — that legitimizes you. Because of the way things are. The reality of it is there’s a lot of guys that have played great years on bad teams and didn’t end up winning. But when you win that thing…

You had five boys who were athletes. What did you learn from that?

All five of my boys have all played both football and baseball, and I did find there’s a period where they hit that puberty and they start growing and their elbow joints get loose because it has to because they’re growing. And I think you really have to be careful about how much they throw. My kids never had arm problems. Joe could throw 200 footballs a day without thinking about it. But throwing a football is not anywhere near as stressful as pitching or throwing a baseball hard. You have to be wary of that. So the summertime, we would just shut them down and they would take some time off so as a result he was never in a camp, really.

Stephen Vincent Flacco, Joe Flacco’s son, next to his dad’s 2012 Super Bowl trophy.

How is Joe as a father?

He’s a good dad; he wants to be a good father. He enjoys being part of a large family — he’s got three boys of his own and a little girl — which is a lot of fun, especially when you have a lot of brothers. I wouldn’t change anything about him. He would be like: “Sure you do, you had a lot to do with it.” Well, that’s true.

What’s your advice for all the dads out there?

When parents realize their kids like something, it’s a lot easier to get them involved and that’s a big part of whether they’re going to continue to get better and work hard at it. If you can find something they like — I don’t care what it is, it doesn’t have to be sports — get them involved and see that they want to do well and work hard. That’s why if you expose them to more things sometimes you’re more likely to find one. They want to be good and they want things from you, now they’re looking for you for help at those early ages, and those are things that don’t just go away. Those things go a long way.

This article was originally published on