Problem-Solving is the New Discipline

There’s nothing wrong with exercising parental authority on occasion, but if the decision-making process doesn’t include a wide range of consequences, it’s not giving kids what they need to be successful adults.

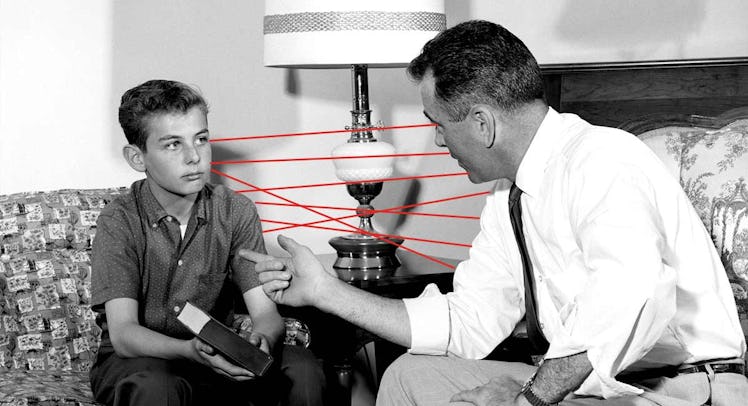

Kids and parents will disagree. And kids and parents will fight. But if yelling “My way or the highway!” is a parent’s primary way to exert authority and resolve conflict, they are not giving kids the tools to thrive, and are making their own job harder. Not that it’s bad to exercise parental authority, or that helicopter parents who solve every problem and shield their children from accepting responsibility are better. Neither approach helps kids develop the skills necessary to make good decisions. Instead, parents should take the time when kids are young to walk them through the decision making process, to consider consequences – all of them – and then to experience those consequences.

“Basically, if parents do the problem solving for their children, that becomes a learned helplessness that follows them, and whenever they encounter a problem they immediately assume that somebody else is going to solve it for them,” explains Alison Kennedy, Ed. S, a school psychologist. “As they start to get older and older, through elementary school and middle school and even high school, kids suffer from this learned helplessness, and any problem they encounter they assume most of the time that a parent is going to swoop in and solve.”

As a result of this learned helplessness, kids struggle with advocating for themselves or resolving minor peer conflicts. Small or normally inconsequential problems can become insurmountable, even into adulthood. This can cause tension and dysfunction in family relationships, peer relationships, romantic relationships, academic or professional settings – any place where differences of opinion exist and compromises will need to be met.

So what exactly is the problem-solving skills kids need to be taught? That problems have more than one solution, and each solution has its own effects. These are the natural consequences of an action – not just punitive consequences from a parent or other adult, but the social and emotional implications for everyone involved in the solution.

“If I am having a problem with my friend, for example, and instead of solving it, I yell at them, and then I walk away, the natural consequence is that person probably doesn’t really want to be my friend anymore,” says Kennedy. “And maybe the other people around that person who witnessed are kind of having weird thoughts, or are thinking ‘Gosh, that seems like an overreaction.’ And so those are some kind of natural consequences that then occur. But the other consequences may be that I feel better, like yelling at that person was such a great release. So there’s two different consequences from one solution: I feel better, but then, I also have to think that these people don’t want to be my friends, and now I am going to feel crummy that nobody wants to be my friend.”

That seems obvious to adults with fully-formed prefrontal cortices, who perform those calculations so frequently and so quickly it barely registers. But these implications are not evident to small children, whose brains are still developing (and will be into their early twenties.)

Parents can introduce these ideas into a disagreement or discussion, but it’s best to pick the battle. Once a child is already emotionally invested in a consequence, it can be hard to persuade them to see it another way. If they’re tired or hungry, they probably aren’t receptive to a thought experiment, either. But when everyone is calm, a measured exchange is the right opportunity to guide their thought processes. Parents could start by offering kids alternatives to what they suggest and asking leading questions about each option: What if we did this? What do you think would happen? How would you feel?

“If you start with something that they aren’t emotionally invested in, they can start learning the concept,” explains Kennedy. “So when they are emotionally invested, they think ‘Oh, I have done this a bunch of times. I know the routine: I should think of two different outcomes, I should try and think about how other people feel, I should think about what the consequences are, and I should think about how I feel about myself.’”

These changes won’t happen overnight; this is a process. And conversations that start calm may not end up so. But even then, there are opportunities for learning. After the discussion has taken place and a decision has been made, parents should revisit the topic in a calm moment and talk with kids about what they both think and feel about the decision, how the decision turned out, and if they would do it differently next time. This is a practice that can be applied after any disagreement, civil or otherwise.

Ultimately, both parent and child learn to communicate better by practicing communication. Establishing that relationship early gives kids experience in navigating their world, and builds trust between parent and child – trust that is going to make adolescence and young adulthood less stressful for both.

This article was originally published on