How Can Parents Help Kids With Anxiety? Be Less Accommodating.

Often, a parent's attempts to accommodate an anxious child make matters worse. Here's how one program can help.

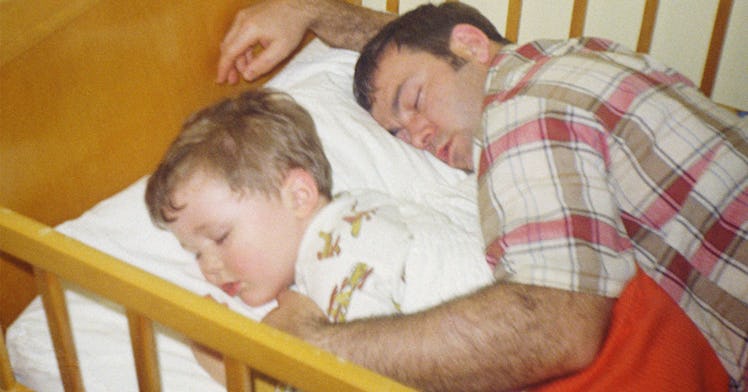

Most kids experience anxiety from time to time. As parents, it’s natural, and even instinctive, to remove the anxiety triggers altogether. Maybe you let your scared-of-the-dark preschooler sleep with you a few nights a week. Perhaps you have a habit of skipping get-togethers so kid with anxiety won’t have to talk to new people.

Well-meaning as these measures may be, such attempts at helping anxious children not only fail to alleviate the problem but can also worsen a child’s anxiety. That’s why Dr. Eli Lebowitz, a professor at the Yale School of Medicine who studies child and adolescent anxiety, created a treatment program called Supportive Parenting for Anxious Childhood Emotions. It’s more or less AA for helicopter parents, a safe space where parents can understand and accept that what they do might be causing anxiety in their kids and that teaches them better ways to cope.

Treating Anxiety in Kids By Teaching Parents

Dr. Leibowitz very much understands the tendency a parent has to accommodate an anxious child. The nature of the parent-child relationship makes that easy. “We’re hardwired to respond to our anxious kids, just as kids are hard-wired to look to their parents,” he says. The problem is, Dr. Lebowitz’s research shows that high levels of parental accommodation are linked to more severe child anxiety symptoms and worse outcomes with treatments like cognitive behavioral therapy or medication.

That’s why he created Supportive Parenting for Anxious Childhood Emotions, also known as SPACE. The program informs parents of anxious children how they may be accommodating their anxious behavior and instructs them to respond to their kids’ anxiety in a way that actually helps the problem. “It helps parents approach the problem differently so it doesn’t blossom into a bigger problem,” says Dr. Lebowitz. “And if a child’s anxiety is already severe, it can help treat the disorder.”

While some kids might be candidates for their own cognitive behavioral therapy, SPACE is an entirely parent-based treatment. According to Dr. Lebowitz, between 95 and 100 percent of parents say if they have a child with anxiety, they frequently engage in accommodation of the symptoms.

So, by teaching parents new ways to respond to their children’s anxiety, SPACE is shown to dramatically improve kids’ mental health outcomes. This year, Lebowitz and his colleagues conducted a randomized, clinical trial with more than 120 children who had severe anxiety disorders and assigned either cognitive behavioral therapy or 12 weeks of SPACE.

What they found was that children who received SPACE were as likely as children who received cognitive behavioral therapy to be in full remission from their disorder or to have significant improvement in their anxiety symptoms.

How the SPACE Program Helps Parents Help Kids With Anxiety

So, how does SPACE treatment work? Parents can attend two-day workshops taught by Dr. Lebowitz, or undergo their own SPACE therapy with a local provider trained in the approach. In either scenario, Dr. Lebowitz says the goal is to equip parents to make two primary changes in how they behave toward their anxious kids.

During the first phase, parents learn what Dr. Lebowitz calls “supportive responses” to a child’s anxiety — any response that shows acceptance or validation of what the child is feeling. For example, a parent with an anxious child might say “I understand you’re uncomfortable right now, but I think you can handle it.”

After practicing with exercises and role play in therapy, parents can go home and implement the changes with their kids. While accommodating sends a message that anxiety should be avoided, Dr. Lebowitz says acceptance can show the child confidence that they can feel anxious. “We’re showing our kids that we as parents believe they can be anxious some of the time and still be okay,” he says.

In the second phase parents learn how to reduce the accommodations that could be exacerbating their children’s anxiety. Dr. Lebowitz has parents create an “accommodation map” where they identify areas they need to work on. Then, they choose specific targets for areas they want to reduce accommodations along with creating a clear plan for what to do instead.

For instance, if you want to encourage your child not to sleep in your bed, you’d come up with a plan for communicating the change. And since your child likely won’t be happy about the adjustment, you’ll also gain some troubleshooting methods for the inevitable (and painful) “you don’t love me” moments.

When reducing accommodations, it’s important to take it one step at a time. “You can’t reduce all accommodations at once, because there’s so much pressure on parents to be accommodating,” Lebowitz says. “Not only because they feel bad that their child is suffering, but also because they need to get through the day; they need their family to function.”

The Big Takeaway

If your child has an anxiety disorder or regularly displays symptoms of anxiety, you may want to consider SPACE as a resource. The program is continuing to grow, with more and more providers across the country.

But even if you don’t participate in the program, you can still apply the premise in your family. Focus on altering your approach: Instead of protecting your child from anxiety, support them so they can learn to cope. “That’s a great gift to give a child with anxiety,” says Lebowitz.

And in the process, don’t blame yourself. Keep in mind that even though parental anxiety is statistically correlated with child anxiety, you’re probably not the cause of the problem. “Two things being correlated doesn’t mean one thing is the cause,” Lebowitz says. “Of course, very bad parental behavior is a risk to children, but that’s not what’s happening in the vast majority of anxiety cases.”

This article was originally published on