I’m a Widow and a Mother. I Teach My Son the Art of Life After Death.

I lost my partner in life and my son lost a parent. For us, the question isn't how to move on -- it's how not to.

My husband had the most magical voice, a lilting Texas drawl equal parts homespun and orchestral. He had little percussive expressions. He called me Bilo, after a character in Borat, and referred to himself as The Badger, after a preposterous ski hat he insisted on wearing. When I texted him a photo of my positive pregnancy test, he texted back “Who’s the daddy?”

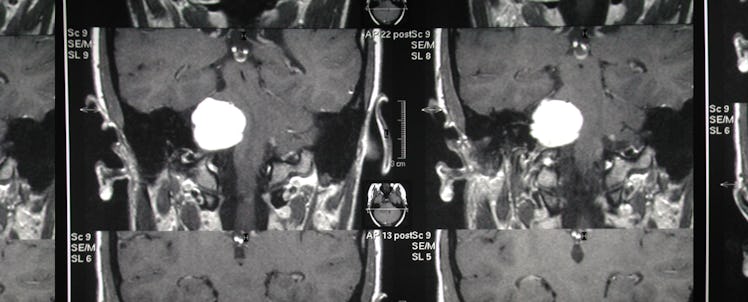

He died of a malignant, relentless brain tumor when our son was a year old.

I remember the child development specialist urging me to explain his death in the simplest terms to my son and to keep his father’s memory alive by telling stories and leaving his picture on the wall. I did that before our son even understood what I was telling him. I told him stories as he fell asleep. I papered our walls with photos of my husband holding our baby, playing with him in Central Park, toting him around in a front-facing carrier, and showing him the dogs at the run. I gave pride of place to a photo of him eating queso at a Mexican restaurant back home in Austin.

When I began to forget the sound of my husband’s voice, I watched videos of him burping our child. I repeated stories about dogs and mice and wine and the things that collectively form a shared life. This made me feel less alone among the mothers and fathers for whom the word “widow” sounded antiquated or not-quite-right.

What I never considered was the effect it was having on our child.

But, as our son got older, I noticed that he would shrink back a little when I brought up his father. He’d nod or maybe smile and sometimes push for a detail or two, but he largely didn’t pursue this history.

Once in awhile, he’d ask me whether daddy, like him, liked to build Legos or listen to rock music or come up with crazy jokes or fire Nerf guns. Yes, yes, yes, and yes. But his relationship with his father was through me, my stories and my grief. My son was asking about his father to comfort me. He was playing the role of a willing audience because I required that. At seven-years-old, he was shouldering an emotional burden.

Earlier this year, we were on vacation in Florida. I offhandedly told our son that daddy would have loved the beach resort. He didn’t respond. So I asked him, quietly, how he felt when I brought up his father.

“Mommy, I don’t mean to hurt your feelings,” he started. “But I don’t want to talk about daddy. I wish he could come back. But he can’t. And that makes me sad.”

My second grader had calmly articulated a feeling I had housed, but not inspected: You can’t force someone to miss what they never had or to love someone they never knew. I would have to be enough for our son. And maybe I could be.

I know what my son has lost because I’ve worked tirelessly to try and make up for it, which I can’t. My son knows his father isn’t going to teach him to ride a bike or catch a baseball or sit with him on a beach in Florida. Stories don’t deposit daddy at the dinner table. All they’ll do, at this point, is make my son dwell on the unfairness of random, metastasized loss.

Yesterday my son had a playdate with a new friend. When this child’s mother dropped him off, she mentioned to me that my son had casually dropped a comment about his dad being dead in the context of a longer conversation about soccer strategy. I was proud to hear that — proud of my son and proud of myself.

Loss is not a progressive malignancy. It is neither treatable nor deadly. It is a cohabitant and a companion. It’s a presence my son knows better than he’ll ever know his dad, no matter how many photos I hammer into the wall. It’s part of his life and mine. So I’m giving him a break from the stories and myself a break from the obligation of telling and retelling.

I’m going to have to be enough for myself and for my son. I was enough for my husband.