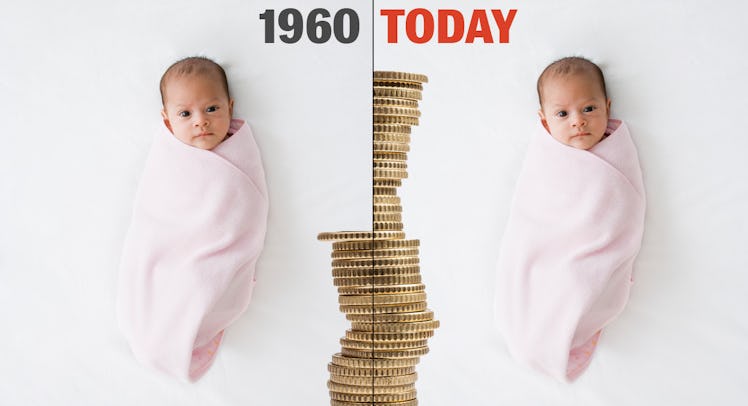

It Cost $31,000 More to Raise a Kid Today Than in 1960. Where’s All the Extra Money Going?

From food and clothing to housing and diapers, the percentage of a family's budget being spent on kids continues to drop. So why is the cost of raising a child still skyrocketing?

Raising a kid has never been cheap. Diapers cost money and tiny mouths need to eat. According to the United States Department of Agriculture’s annual breakdown of child-rearing costs, it now runs parents around $13,290 a year to raise one child ⏤ or $233,610 all told to get them out the door to college. That’s $31,000 more than it did in 1960 (adjusted for inflation) when the USDA started tracking the numbers and a single kid cost about $11,883 a year. And it may explain why more Americans want to have families with three or more kids, but are still sticking with one or two.

Here’s the interesting thing though. While the overall cost of raising a child has skyrocketed over the past 58 years, it’s never been cheaper to feed, clothe, or otherwise care for a kid. Many of the highest expenses ⏤ food, shelter, and transportation ⏤ have either remained constant or are on the decline, consuming less of a family’s budget than they did in 1960 according to the USDA. Today, around 16 percent of a middle-class household’s total before-tax income (around 27 percent for lower-income families) is allocated to raising a kid ⏤ in 1960, it was 26 percent.

But if that’s the case, why is the cost still going up? And what expenses are eating up that extra money? We took a look at the most recent numbers to see what’s changed over the past 60 years, and found the results both surprising and completely expected.

First, What’s Omitted: Pregnancy and College Tuition

The most sobering reality of the USDA’s annual Expenditures on Children by Families report is what’s not included: Expenses related to life before and after a kid enters or leaves the house. That includes “prenatal care, fertility care, childbirth, and adoption” and college tuition. So while it might be tempting to assume the extra $31,000 now includes the cost of giving birth ⏤ anywhere between $5,000 and $14,000 depending on your state ⏤ or the rising cost of tuition at a four-year public college (now $9,410 per year), it doesn’t. Those expenses remain both extra and steep. The $233,610 only accounts for the 17 years during which a child is living under your roof.

Where the Money Isn’t Going: Diapers, Clothes, or Sporting Goods

Pampers debuted in 1961 and cost $.10 per diaper ⏤ or a whopping .$84 each in 2018 dollars. Today, an 84-count box of Pampers Swaddlers runs $25, or a paltry $.29 a diaper. Thanks to advances in technology and production, as well as the growth of global trade, the cost of diapers, clothing and most household incidentals, from shampoo and toothbrushes to rash cream and dishwashing soap, not to mention “portable media players, sports equipment, video games, and reading materials” have all fallen, according to the USDA. In 1960, the average middle-class family spent 11 percent of their budget on their kids’ clothing and shoes and 12 percent of everything from haircuts to baseball gloves to transistor radios. Those slices of the pie are down to six percent (clothes) and seven percent (miscellaneous goods and services), and that even takes into account the rising cost of youth sports.

The Big Three ⏤ Housing, Food, and Transportation ⏤ Have Also Decreased

Since the survey’s inception, the largest bills parents have had to foot are housing, food, and transportation. That’s as true today as it was in 1960 ⏤ all three still constitute the three highest expenditures. Except there is one big change, all three have dropped as a percentage of a family’s spending. Housing prices have skyrocketed, yes, but incomes have also risen and as parents have fewer kids, they require fewer bedrooms ⏤ and thus less expensive house or apartment. Whereas the typical family spent 31 percent of their income on housing 60 years ago ⏤ that includes everything from mortgage to utilities to furniture ⏤ today it’s 29 percent (even lower for high-income families) ⏤ around $3,680 per child per year or $66,240 over the course of a single kid’s life.

Meanwhile, it may not feel like it when strolling through the grocery store, but food prices have plummeted precipitously since 1960 thanks to improvements in agricultural production. Food used to eat up almost 25 percent of a family’s budget. Today, it only accounts for an average of 18 percent, or between $1,620 and $2,860 per year depending on the age of the child considering that, like most expenses, the cost of raising a kid grows along with the child ⏤ the bigger the kid, the more they eat.

Finally, shuttling kids between school, soccer, and saxophone lessons gets expensive. While transportation costs related to raising kids includes car payments, insurance, and maintenance, the number tends to fluctuate based on gasoline prices. That said, it’s remained relatively constant as a percentage of parents income over the last five decades. In 1960, it constituted 16 percent of the budget; in 1995, it was around $22,110 per kid; today, it’s down only a percentage point to 15 percent ⏤ between $24,750 and $49,770 for 17 years based on a family’s income. So despite Americans obsession with SUVs and all the extra scheduling kids have in their lives, it hasn’t made much of dent in the cost of moving kids around.

The New Culprits: Child Care & Education and Health Care

And so it boils down to two big expenses driving the explosion in child-rearing costs. First, health care expenses continue to balloon in the United States. According to the USDA data, the price of out-of-pocket medical and dental services not covered by insurance and prescription drugs has more than doubled to around nine percent of a family’s budget, up from four percent in 1960, and accounts for between $1,180 and $1,300 a year per kid. In addition to the fact that health care, in general, is more expensive these days, the figure also takes into account the rise in childhood chronic illness and the growing number of kids who suffer from obesity, food allergies, asthma, and diabetes ⏤ all of which are on the rise.

And finally, it shouldn’t come as any surprise to parents with kids under 4 years old, but childcare is what’s busting family budgets the most. In 1960, when most mothers stayed home to watch the kids, child care accounted for only two percent of a household’s income. By 1995, that number had grown to 9 percent or almost $9,870 per year. Over the last 20-plus years, however, thanks to the continued growth of two-income families, childcare & education ⏤ which includes “day care tuition and supplies; babysitting; and elementary and high school tuition, books, and supplies” ⏤ has overtaken transportation as the third highest expense at 16 percent of the budget, or around $38,040 over the course of a child’s life. Not surprisingly, child care expenditures are shaped by family income more so than other expenses, as wealthy families ante up for expensive daycares and schools ($86,820 for 17 years) while lower-income parents rely more on grandparents for childcare, spending only $21,240.

This article was originally published on