What It Was Like to Be Raised by Renowned Physicist Michio Kaku

“Looking back, I think explaining the complicated ideas behind these projects to us as kids helped him to figure out how to communicate about science to the masses.”

Michio Kaku, born in 1947, is an American theoretical physicist. A professor at the City College of New York and CUNY Graduate Center, Kaku is co-founder of the string field theory, a major step toward potentially uniting the fundamental forces of nature into a grand unified theory of everything. As a best-selling author, on-air personality, and regular guest on myriad talk shows and science programs, Kaku has also become one of the country’s most well-known disseminators of scientific topics to a general audience. Kaku lives in New York City with his wife, Shizue. He has two daughters, Alyson and Michelle.

When I was in high school, my father would look over my shoulder while I studied at our dining room table for the New York State Regents Exams, the mandatory statewide standardized tests, and become visibly frustrated.

“Why are you memorizing these lists of rocks?” he’d ask, gesturing to my study guide for the Earth Sciences section of the test. “When are you going to use this information? No wonder our youth are not going into the sciences!”

My father spent most of his day in constant rumination. Whenever I think of him now, the first image that comes to my head is him twirling a lock of his long, wavy hair with his left hand and drawing equations in the air with his right, all the while looking off into space. “I get paid to think,” he used to tell me. “It’s the best job in the world.”

To him, the idea that children weren’t being inspired by their school curriculum to pursue careers in the sciences or other intellectual ventures was a grievous mistake. It’s why he took it upon himself to show my sister and me just how exciting and practical these fields could be.

He used to leave big, evocative science books around the house, like Asimov’s Biographical Encyclopedia of Science and Technology, filled with pictures and ideas far more fantastic than the sort of stuff we learned in school. And he’d bring home DIY science kits, which we’d used to create chemical reactions or generate our own electrical current. I was in awe when we managed to illuminate a light bulb with little more than some copper wire and a magnet.

As I got older, he never stopped opening our eyes to the wonders of science. The experiments simply grew more complex. When I was a teenager, our father-daughter bonding time included building a Wilson cloud chamber, a particle detector that allowed us to photograph the tracks of antimatter (i.e. positrons). We trekked all over the city, heading to the Lower East Side for dry ice and Chinatown to find craftsmen willing to make us a specialized plastic cylinder we could use for our cloud chamber. Once we’d obtained radioactive isotope samples through the mail, we put it all together and watched as the ionized particles left tiny curving trails on the piece of velvet cloth we’d placed inside the chamber, capturing their movements with a fancy new digital camera we’d purchased for the experiment.

Looking back, I think explaining the complicated ideas behind these projects to us as kids helped him to figure out how to communicate science to the masses. The way he describes scientific topics on television and radio programs now is the same way he used to explain them to us when we were young. I wish this same hands-on way in which he engaged us in learning science could be instilled as early as kindergarten.

But it wasn’t always so serious. My father loved Star Trek, since he was fascinated by the idea of future communities around the globe working together to explore other worlds, and his passion wore off on me and my sister. We’d religiously watch new episodes of Star Trek: The Next Generation with him every week, and together we assembled a plastic model of the Starship Enterprise. Since then I’ve always been a true fan; my family threw me a Star Trek–themed bachelorette party, complete with out-of-this-world bubbly green drinks and a sign on the wall that read, “Love long and prosper.”

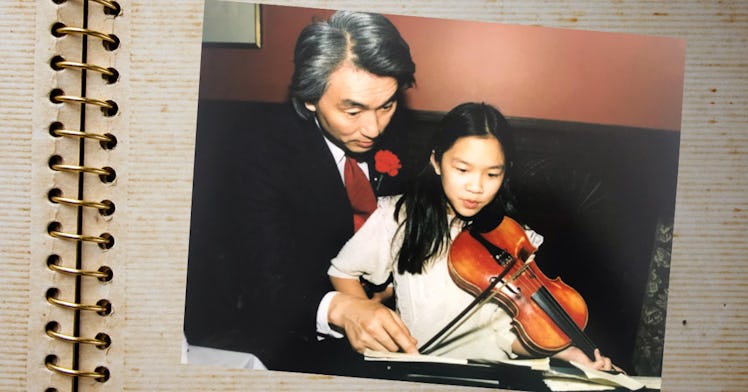

Dad encouraged us to be creative. He encouraged us to have hobbies, and fostered my sister’s love of painting and making pottery. He sat with me for hours while I practiced the violin, listening to me play the same lines over and over again without ever seeming to mind. And he took us ice skating every week, eventually becoming an avid skater himself. He and our mom encouraged us to follow our dreams, whatever they might be, just as long as we pursued them to the best of our ability. He’d say to us, “If you find your passion is garbage collecting, that’s fine, but you better be the best garbage collector ever, if that is where your passion lies.”

When my sister fell in love with cooking and baking, my parents purchased new cooking utensils for the kitchen, helped her organize special cooking nights at the apartment, and encouraged her to seek out internships at prestigious restaurants. Now Alyson is a successful pastry chef.

For a while, I thought I wanted to go into theoretical physics like my father. But in college, I realized I really enjoyed interacting with and helping people, which didn’t fit perfectly with the frequently sequestered lifestyle of a physicist. So, I chose a different path in the sciences, went to medical school, and followed my own path, eventually becoming a neurologist. Now I am an assistant professor at Boston University School of Medicine. As director of the school’s neurology residency program, it’s my job to motivate the next generation of neurologists. Thankfully, I’ve had a lifetime of practice being inspired and years of sitting with my father to guide me.

Michelle Kaku, M.D., is the director of the neurology residency program and assistant professor of neurology at Boston University School of Medicine.

This article was originally published on