Why I’m Raising My Kids to Be Critical Catholics

I want religion to be part of my kid's lives. But I also what them to think rationally about religion to ensure they're open to everything.

I’ve always considered myself a Catholic, and my family, a Catholic family. When I was growing up in the South Bronx, there were few places for a small, nerdy boy to find peace. I had school and comic books, yes. But I also found solace at my local Catholic church. I had a positive experience with the church. I was an altar boy, had a good relationship with the people of the parish, and went to Catholic school. Over the years, the priest that gave me communion and confirmation, conducted my pre-cana and my wedding ceremony, and later baptized my first born.

But growing into adulthood, things changed. I read and really enjoyed learning history. I went to one of the most liberal schools in the country, and fully embraced their critical analysis approach, which I applied to everything. This meant that I couldn’t ignore that the institution I viewed as uplifting, was also the institution that had done some tremendously terrible things, including direct involvement in such atrocities as the crusades, the inquisition, the conquest of native peoples, and the slave trade. I was torn that the church seemed to think that sexual freedom was a sin and deliberately dragging its feet on gender equality. I also couldn’t ignore that there where members of the cloth who had betrayed the trust given to them by the very people they were supposed to protect.

So as a father, I wondered, how could subject my children to a religion so fundamentally flawed?

Since the beginning, my daughters and I have had a pretty intellectual approach to religion. We’ve talked about the presence of God, both as belief and concept, and the first book my eldest could read on her own (or had memorized) was her good night prayer book. I always told her that there were other religions out there, not just throughout history, but among us today, and most people believed their faith to be “the right one.” Not that anyone else’s is “wrong,” but that what they believed was true to them. When we read greek mythology, for example, I made sure to explain that for many years, people believed these stories to be true and now, they are amazing tales. My goal was to teach acceptance of different religions which was in keeping with our own family’s progressive/liberal beliefs.

Now I send my children to a Catholic school, which does present challenges. They have a class on religion, where they receive a grade that affects their GPA. They go to church as least once a month on the first Friday, and around all the holy holidays. And some of the teachers betray a more conservative “bias” during social studies and presentations of news of the day.

My eldest daughter takes after her parents in terms of looking at things critically, and isn’t afraid to vocalize her thoughts She participates a lot in discussions, and challenges other students who simply reiterate what’s in their book. Thanks to our long car rides and conversations, during which we discuss everything from Howard Zinn to Paulo Freire, she has historical examples to back up her challenges to which most kids her age can’t respond.

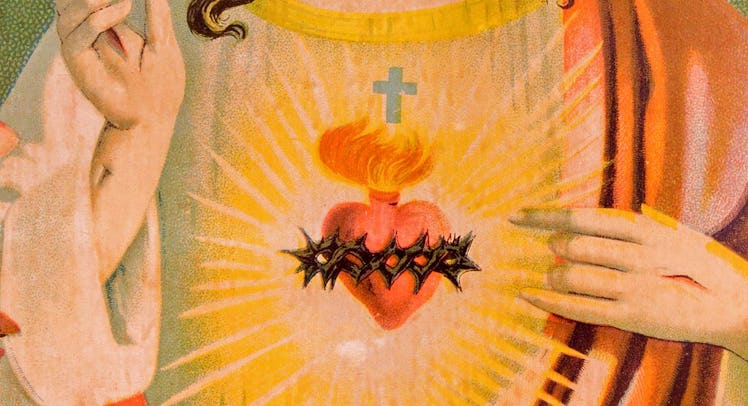

This all has produced some awkward conversations with teachers during parent conferences. They applaud her leadership and active participation, but it’s obvious that some wonder if she’s challenging their authority. One time my daughter proudly told me how she commanded a debate among her friends, where she steadfastly declared that Jesus was brown — that there was no way historically he could be blonde and blue-eyed like they have in the pictures, especially if he was native born to the region. I was proud, but still winced at the image of the faces that must have contorted during that scene.

And so we talk a lot about what it means to be Catholic. I explain to her that the modern Catholic church has done some great things, especially in medicine, poverty reduction, and education. I tell her the Church is an ally of immigrant families and advocates on their behalf. That the current pope has been changing the discourse to a more accepting environment. That there is a lot of good the Church has done.

I also say that she doesn’t have to take everything as ‘gospel.’ That the religion and the church are made up of humans, and humans are fundamentally flawed. And to be skeptical of anyone who says they “speak for god,” especially if they are using that to compel people to do things against their own interest or against others. I tell her that it’s usually the “people” part that corrupts the ideal, and that it happens in every religion.

One day during one of our long drives, my daughter drops the big question. “So is Jesus even real? Are we even Catholics?” This question came after I noticed her religion class quizzes were slipping, and to her admitting that she just didn’t really care for the class that much.

I thought about it, and told her this: “Regardless of whether you believe Jesus is God or the son of God, he was a bad-ass in his time. He challenged authority, told people they didn’t have to accept their position as being below anyone, that we were all equal. This was a new way to think about things because before, you had your role, your class, your station, and you just accepted it. So this guy — he’s like no, you don’t. And so he went and hung around with people who were the most vulnerable in society, the sick, the castaways, and told them they had value.”

I continued to explain to her that he was killed because he challenged the status quo and people ultimately feared change. They feared he’d start a revolution and Rome would then come and wipe them out. Regardless of the religious aspect, that’s the truth.

“But the real miracle,” I continued, “is that after all this happened, rather than an idea dying with Jesus – it spread to most of the world. And the more you learn history, the more you are going to see this people who give their lives to challenge the current structure of things and inspire change.”

In that way, I told her, being Catholic is kind of cool. Does that mean we have to go to church every Sunday? Only if you want. Some people like to go, others don’t. Does it mean we have to accept all their rules, such as those that say women can’t be top leaders, or their stances on sexuality or birth control? No, it doesn’t.

I finished by tell her this: “What it means is that you have to learn how to be a good person from somewhere, and Jesus is as good a teacher as any. So yes, you should consider yourself Catholic, but be a critical one, one that thinks for herself, and questions authority when necessary, and one who understands that humans are imperfect, and that includes the institutions they create. Because guess what? That’s what Jesus believed, too.”

“I never thought about it like that Daddy,” my daughter told me from the back seat of the car.

We also talked about the right way to present arguments in class, and how to read the room so as to decide how hard to push, and to always listen to other people’s arguments as well. I also warned her that her American History class would be a challenge in future years. I warned her teachers that it would a challenge for them, too.

From then on, her quiz scores were back on track; some were even better. My daughter started seeing religion not as doctrine but as a blueprint for activism. For that, I couldn’t be prouder.