What It Was Like Having Civil Rights Activist Cesar Chavez for a Father

"My dad understood individual lives and successive generations would be forever changed and people uplifted if they were given the chance to negotiate their own union contracts. He asked me to be part of it."

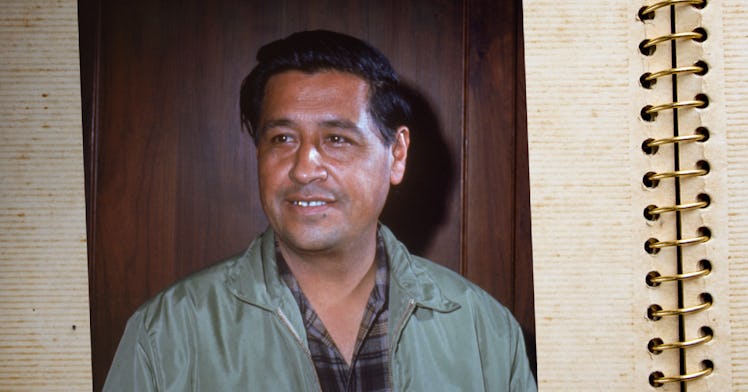

Cesar Estrada Chavez was born in 1927 in the North Gila River Valley outside Yuma, Arizona. He was a major labor organizer and civil rights leader who founded the National Farm Workers Association in 1962. Under Chavez’s leadership, the NFWA — now the United Farm Workers union — became nationally recognized. He led the famous Delano grape strike — which lasted five years and ended with the UFW getting their first union contract with growers in the area. Beyond strikes and marches, Chavez focused on pushing legislation that protected farm workers through a range of tactics, which included fasts. During this time, Chavez and his wife, Helen Fabela Chavez, raised eight children: Elizabeth, Anna, Linda, Sylvia, Paul, Fernando, Eloise, and Anthony. Chavez passed away in 1993. He is buried at the National Chavez Center in Kern County, California.

I remember once writing my name on the ceiling above my dad’s bed. I assume it was my way of saying, “Hey, Dad, don’t forget about us.” Unlike others, my father didn’t take me to Little League games because he was constantly working to build the farm worker movement. I don’t remember doing a lot of things my friends did with their fathers because my dad was on the road, organizing. One of the many sacrifices he made was not spending time with his children.

But there were important consejos, or life lessons, I learned from my father. They still offer me direction.

One of those lessons is having faith in people. At the heart of our movement is the unfailing faith my dad had in the poorest and least educated — believing they could challenge one of California’s mightiest industries, and prevail.

After high school, I decided to work full-time with the union. I wanted to be an organizer. My father promptly put me to work in the United Farm Workers’ print shop, something I knew nothing about and had no interest in. But I became a pretty good printer, and enjoyed it.

After a few years, my dad asked me to work with him as an assistant in his office. I resisted. I thought I was born with ink in my veins. Besides, I had never worked in an office. I finally joined his staff, did well, and became interested in how plans and budgets are made, how you identify issues and allocate resources to solve problems — tools I still use today.

By then, the union had achieved much success in organizing workers. It needed negotiators to bargain union contracts. Some union leaders wanted to hire experienced outside negotiators. My father was convinced the sons and daughters of farm workers could learn those skills. But they would need training and opportunities to make mistakes while learning.

My dad understood individual lives and successive generations would be forever changed and people uplifted if they were given the chance to negotiate their own union contracts. He asked me to be part of it. I was content to be an administrative assistant. But he insisted, and I joined the first class of 15 students training to become negotiators at a school he established at our headquarters. It was a tough yearlong academic curriculum. After graduation, we worked hard, made some mistakes, but gained confidence going up against seasoned grower negotiators, many of them lawyers.

By that time, I thought my calling was as a negotiator. Then my father asked me to become the union’s political director and lobbyist. That also took convincing. I knew nothing about those things.

New hostile administrations were taking over in Washington and Sacramento. The incoming California governor campaigned on dismantling the historic state farm labor law letting workers organize that my dad worked hard to pass under Governor Jerry Brown. So I learned the legislative process.

After a couple of years, my father pushed me to leave the lobbying and political job to take over and build what today is the Cesar Chavez Foundation. I asked myself, what do I know about affordable housing and educational radio? But my dad was confident I could do the job.

Today, I realize at every step of the way I was not sure I could do these jobs. I lacked confidence. Yet my father was persistent. He encouraged and pushed me at each turn. And I came to realize that my father had more faith in me than I had in myself.

Today, we take part in Cesar Chavez commemorations across the nation. I meet men and women he personally influenced — and they tell me their stories. There was the young woman who was a teacher’s aide. My dad convinced her to become a teacher. She became an administrator, and today is a district superintendent.

There was the paralegal, the son of striking farm workers, who was challenged by my father to become a lawyer. He is now a Superior Court judge in Kern County.

And there was the nurse who became a doctor at my dad’s urging.

My father gave people opportunities no one would have given him when he was a migrant kid with an eighth-grade education. Whenever he met young people, especially if they came from farm worker or working-class families, my dad challenged them to believe in themselves and their capabilities. He helped hundreds fulfill dreams many didn’t even know they had at the time.

It finally dawned on me: What I thought was the love a father has for his son, I saw was the love and faith my father had in an entire community — and in the ability of an entire people to create their own future.

The second lesson I learned from my dad is perseverance.

In 1982, as the union’s political director, I led an all-out, statewide campaign to confirm a nominee to the farm labor board and ensure enforcement of the farm labor law. My father and I joined hundreds of farm workers watching the final vote in the gallery above the ornate Senate chamber at the State Capitol in Sacramento. We fell one vote short.

I was devastated. Around 10 p.m., after my dad offered encouraging words to the workers, he said to me, “Let’s drive home.” It was about five hours from Sacramento to our headquarters in Keene near Bakersfield.

After about an hour, my father spoke. He asked how I was feeling. I told him I felt I’d let him, the farm workers, and the movement down. I felt terrible.

“Did you do everything you could do?” my dad asked.

“Yes,” I answered.

“Did you leave any stone unturned?”

“No, I did everything I knew how to do.”

“Did you work as hard as you could?”

“Yes, I did.”

My father said, “Remember our work isn’t like a baseball game, where after nine innings, whoever has the most runs wins — and the other team loses.

“It’s not a political race — where each candidate runs a campaign and on Election Day whoever gets the most votes wins and everyone else loses,” he said.

“In our work, La Causa, the fight for justice, you only lose when you stop fighting — you only lose when you quit.”

My father added, “Let’s go home and get some rest because tomorrow we have a lot of work to do.”

People forget that Cesar Chavez had more defeats than victories. Yet each time he was knocked to the ground, he’d pick himself up, dust himself off and return to the nonviolent fight. The lesson was clear: Victory is ours when we persist, when we resist, and when we refuse to give up.

My dad didn’t take me to Little League games, but the lessons I learned from him are still with me.

Paul F. Chavez is president of the Cesar Chavez Foundation, a social enterprise transforming the lives of Latinos and working families by building and managing high-quality affordable housing, owning a 10-station educational radio network reaching 1.5 million people weekly, providing after-school programs for children, and preserving and promoting the legacy of Cesar Chavez.

This article was originally published on