How My Time in the Army Made Me A More Patient And Empathetic Dad

"The most significant challenge since I've been gone in that time is staying ahead of what the kids are doing from day to day."

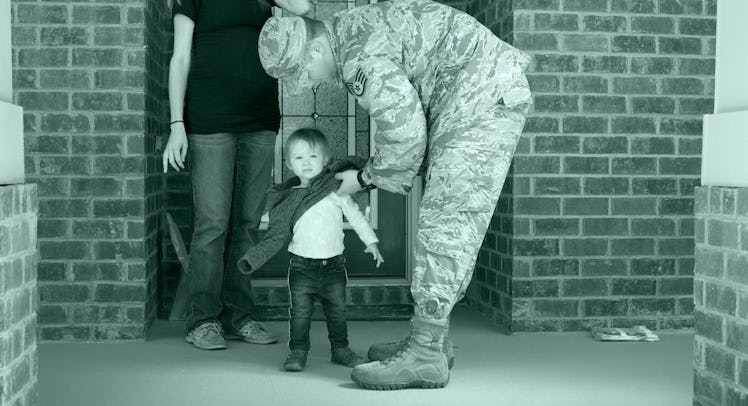

Military families face a unique and difficult set of challenges. Service members with kids quickly learn that a predictable family routine is one of many things they need to sacrifice in the name of duty. While advances in communications technology have allowed military parents to keep in touch with family members half a world away, they’re still, well, half a world away. They miss the daily occurrences other dads take for granted. Like watching their kids savage a bowl of cheerios. Or consoling them after they strike out in Little League. These fathers must work harder to be part of their children’s — and spouse’s — lives.

Fatherly spoke to a variety of military dads about their service, their families, and how they managed to balance the two. Here, U.S. Army Military Police Corps Major Anthony Douglass explains his lifetime of service and the

—

I was born and raised in a small town in Southeast Ohio called Marietta. I am an active duty Major in the U.S. Army Military Police Corps for the last 11.5 years. I joined the military as a zero-experience, “walk on” Cadet at the Ohio State University Army ROTC program in the fall of 2002. The tradition of military service skipped a generation in my family as my dad missed being drafted to Vietnam but both of my grandfathers served; one in the Navy and one in the newly minted U.S. Air Force in the WWII days.

Hands down, the best part of being a military dad is seeing how resilient the kids can be despite the uncertainty that comes with military service.

During the summer between my junior and senior years of high school, my best friend went to basic combat training under the early enlistment option program and I seriously contemplated going with him. I decided against it, but knew I wanted to serve after I watched the World Trade Center fall while sitting in what would have been a college prep English class during my senior year. My initial purpose that drove me to service was a thought that I could somehow “make right” what the world saw on 9/11.

My class of cadets was the first to join as officers in training after 9/11. As my career in the Army progressed, my reasons changed. Following my first deployment to Iraq in 2007, I came away with a better understanding that the military is a people business and not the mechanical tool of vengeance that I wanted it to be. I continued my service after my initial commitment because of the people. Those to my left and right and also those in Iraq and Afghanistan that I met along the way gave me purpose to stay; it is the thought that I can make something better than when I found it.

My wife Stephanie and I have been married for 10 years; we met on the varsity pistol team at OSU and got married in September of 2007 after I had a year of service under my belt. Our daughter Josie will be four this spring and our son Evan turned two in November.

It’s important to have meaningful “talking points” that show the kids I’m engaged even from 4,000-plus miles away.

My service influenced being a dad long before the kids were born. With the ongoing war on terror and general state of global affairs, Stephanie and I knew that we needed to plan out family expansions before they happened. After two deployments to Iraq and one to Afghanistan as a company commander, the time was right. I accepted an assignment as an ROTC instructor in Ohio which is about the most “un-Army” assignment you can imagine: home every night for dinner, no field time, no deployments, and a predictability that doesn’t exist elsewhere in the service. Both of our children were born in a civilian hospital in central Ohio away from any semblance of a military community. In addition to the service influencing me as a dad, the opposite is true as well.

As a military policeman, I review cases that range from neglect to statutory rape and while it is my job to make recommendations to my commander based on facts, I can’t help but think, “What if that were my child?” My service has improved me as a father in a multitude of ways; I’m more empathetic, I’m more patient with communication when a barrier exists, and I’ve also learned how to pick my battles.

I don’t feel at this point in my career that I’ve experienced all of the challenges associated with being a military dad. Prior to my current deployment, life was better than good while living in central Ohio as an ROTC instructor.

My service influenced being a dad long before the kids were born.

The most significant challenge since I’ve been gone the last six months is staying ahead of what the kids are doing from day to day. I feel like it’s important to make contact with Steph and get a rundown of events since the last time I talked to the kids so I have meaningful “talking points” that show the kids I’m engaged even from 4,000-plus miles away.

Most often, we connect through FaceTime video chat. It makes communication more difficult when you have to do it twice in order to keep it meaningful for little ones. But hands down, the best part of being a military dad is seeing how resilient the kids can be despite the uncertainty that comes with military service.

I have been physically absent for the last six months and recently got to come home for leave over the holidays and as a true measure of their own resilience, the kids made it seem like I never left. They are bigger, more independent, more experienced and my 2-year-old says words that I never imagined coming out of his mouth, but to them, I’m just daddy. That is what makes this adventure great.

Fatherly prides itself on publishing true stories told by a diverse group of dads (and occasionally moms). Interested in being part of that group. Please email story ideas or manuscripts to our editors at submissions@fatherly.com. For more information, check out our FAQs. But there’s no need to overthink it. We’re genuinely excited to hear what you have to say.

This article was originally published on