Francois Clemmons, Good Cop on ‘Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood’, Still Has Hope

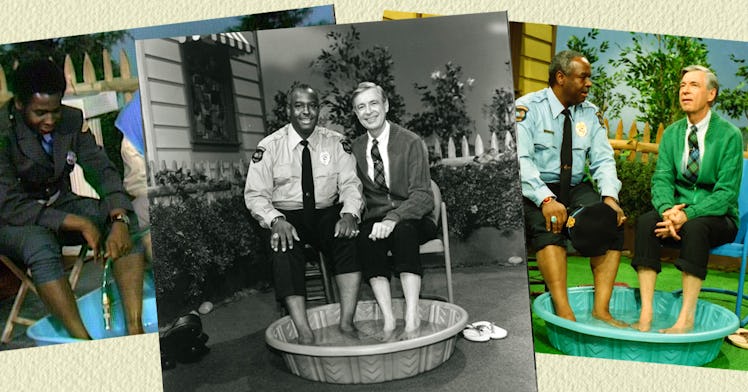

Francois Clemmons showed American kids what a police officer could be if he truly tried to keep the peace.

In 2008, President Barack Obama was elected. In 2009, the gospel singer and educator Francois Clemmons, who played Officer Clemmons on Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood, received a deluge of letters from black men telling him that his thoughtful, peaceful character had inspired them to become police officers. Clemmons was taken aback by the volume of messages. “It’s not what I expected,” he laughed recently when telling Fatherly the story. “People really loved that I was a singing cop without a gun or a club,” he added, but there are far fewer notes these days. This makes each more memorable.

“A couple days ago I got a beautiful letter from a black policeman in Missouri and he said I had been a big influence on him and I thought that was a tremendous compliment,” Clemmons says. “You learn that people have vicarious experiences and that they can be really positive.”

If Clemmons, the author of the newly released and persistently charming Officer Clemmons: a Memoir, is anything, it’s positive. As he talks, he dips in and out of song and speaks so quickly and melodically, it’s hard to differentiate the score from the book. When Fatherly spoke to him, quarantine was taking its toll. He’s an extrovert who lives alone and the seclusion was getting to him. But he treated that suffering as little more than another experience. And Clemmons likes experiences. He’s good at them. Also, he’s getting more and more into meditation.

Fatherly spoke to Clemmons about coping in difficult times, being a minority in Vermont, and traveling America.

We live in divisive times and you live in a very, very white state populated by a lot of people who wear plaid. I wonder if you had concerns when you made the move to Vermont to take a role at Middlebury. What did you expect? What did you experience?

The old president of Middlebury was a man name John McCardell Jr. and I told him very frankly that I wasn’t coming to Vermont to go back in the closet. I told them that ff they say one word their gonna see the other side of Dr. Clemmons. He told me that he’d tell folks to welcome me and I’ve rarely ever experienced anything but that welcome.

That said, I was one in a drug store and a man suggested that I go back to be with my kind. He was tall and I was getting in his face. I was like, ‘I’m taking off my heels and we’re gonna have it out,’ but a bunch of other people came to my aid. I thought, ‘Well, well… this is where I belong.’

It’s interesting because you’re rather famously a guy who is going to do what he’s going to do and that’s not necessarily the New England ethos. But it seems like you have this remarkable ability to sort of be a community officer wherever you go.

I’m good at getting along with people. Senator Patrick Lahey, who is a lovely man, asked me to do a national anthem at a naturalization ceremony. After that I sang for all the sports teams and it was easy and I liked it. I like a crowd and I like dressing in my stage stuff. So I got known for that. People come up and say, ‘Aren’t you guy who sang the national anthem?’ I created these opportunities to invite farmers and handyman onto the Middlebury campus. I discovered that a lot of them didn’t feel worthy of being there or felt uneducated.

When we performed with the choir on campus, we’d sometimes get 50 percent townies in the audience and I was very proud of that. I like bringing people together.

It feels like that’s something Fred Rogers saw in you. I wonder if that’s something that you took from him as well? I’ll note that a lot has been made of the fact that he asked you to keep your sexuality secret for a number of years.

We can carry his ideas forward. I try to do so. That’s a big part of why I wrote a book. I felt like I had a unique perspective on the man. He was warm and kind and sensitive and non-judgmental. I’ll not that there was a difference between private and public life. It’s true that Mister Rogers the brand wasn’t going to touch being gay — there was still a lot of homophobia and hostility — but Fred Rogers the human being was incredibly loving and accepting.

When he asked me to be on the show, it was because he saw me singing in a church. I said I would be glad to be on the program if it didn’t interfere with my singing. It was very bold of me. He said to me later, ‘That was the moment I loved you because you weren’t going to kiss my ass.’ I said, ‘Of course. I’m a diva.’

It’s funny because Rogers has been critiqued for not supporting you and also posthumously “outed” by sources saying he was a bisexual, which feels like a reach.

Ha. I know. But there’s no story there. People called about that and I listened to what they had to say then respectfully told them that they weren’t talking about Fred Rogers. He wasn’t gay or bisexual and he didn’t want anything on the down low. Believe me. He was my surrogate father. I would have known.

It feels like maybe some of that was the LGBTQ movement wanting to claim a piece of Fred Rogers, which is incredibly understandable. He’s this unimpeachable figure in a world where there aren’t many of those left. I think there’s often a hunger for the answer to the question, “What would Mister Rogers do?” I wonder if you think about that.

Well, there’s a lot written about him. We have a good idea what he would do about a lot of things. But he was also a person. Sometimes it feels like people are turning him into an idea, but he was a person. He just happened to be an incredibly special person, a person who behave with kindness and integrity.

Between your time on Mister Rogers Neighborhood and your career as a singer, you’ve had the opportunity to see America from a number of different angles. You seem resolutely optimistic. Why?

My goal when I was young was to sing in every state in America and get paid. The last state I hadn’t sung in was Montana so I drove across the line from Canada while I was on tour with the Harlem Spiritual Ensemble. I went to Whitefish, where there was a nice hotel. The people there were extremely nice to me so I told the manager I had a proposal and explained the situation. I told him we had a day off coming up and asked if we could come to the hotel and do some American negro spirituals. He looked at me for a minute and was clearly thinking, ‘This man is as crazy as he is black.’ He hemmed and hawed. So I told him to take a chance and we’d just pass the basket. He thought and thought and finally said sure.

When we performed, that place was so full of nice country people. I passed the basket and we all sang. It was a great night and let me tell you this: We made thousands of dollars.