The Hardest Thing About A Father’s Legacy? The Truth.

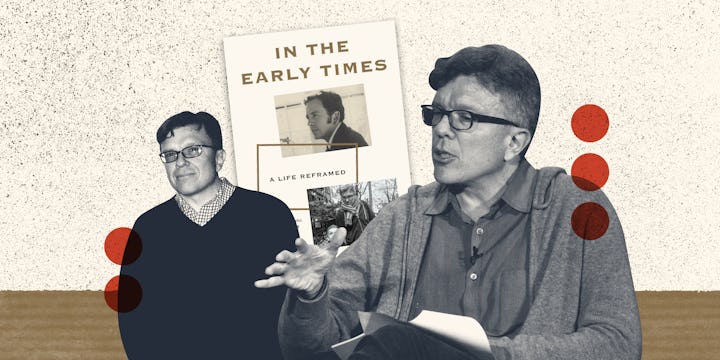

When writing his new memoir In the Early Times, Tad Friend discovered new, hard truths about his father that forced him to reckon with preconceived notions — and himself.

Tad Friend’s memoir, In the Early Times: A Life Reframed, is about his father, Theodore Wood Friend III, the former president of Swarthmore College, a public figure who remained inscrutable to his kids. It’s also about marriage, family, and what happens when one man plunges into the truth behind his widely held assumptions.

Friend’s book is not an easily digestible “Cat’s in the Cradle” lament. It pulses with nuanced honesty. As his father’s health declines, Friend measures every aspect of his own life. On the surface, Friend, 59, has an enviable one. He’s a staff writer for The New Yorker. His family comes out of a magazine shoot, complete with a daughter who wears cat ears and a wife who’s an entrepreneurial dynamo. Firmly entrenched in middle-age, he’s a nationally ranked squash player.

But it’s a facade that couldn’t withstand the rigors of life.

Day, as his father liked to be known, died after Friend turned in his first draft of the book. Then Friend discovered a collection of his father’s letters and correspondences that revealed several truths, including that he cheated on his mother. Then Friend’s wife Amanda discovered his own lengthy history of infidelity. “I wasn’t averse to committing to her completely, I was averse to committing to her completely at the price of being misunderstood,” Friend writes. “Because if she really knew me, she’d realize she’d made a mistake.”

A child doesn’t receive a handbook for their dad, Friend says. And we don’t get one for ourselves. Friend had spent a lifetime distancing himself from his father’s tendencies only to find that he embodied them.

“I think at a certain point I decided I wrote him off and thought, I'm gonna be different and better and smarter and more emotional than he was,” Friend told Fatherly in early May. “And then in the course of writing the book and making discoveries about him and making discoveries about myself, I realized actually, No, there are huge commonalities between us.”

As Friend writes, the weightiest “hand-me-downs are habits of mind.” There’s no happy ending, just work, including reconsidering his father beyond the superficial and casting off the weight of the past. Friend’s vulnerability — good and bad — provides both a warning and serves as an inspiration for fathers of all ages.

Here, Friend, 59, talks about fatherhood, coming to terms with the complicated truth of his dad, working through his mistakes, and whether or not we're ever free of our parents' influence.

Your book is extremely candid. You talk about your dad, your mortality, your marriage, your kids. How are you doing?

I'm doing very well, actually. The process of writing the book was much more complicated than I expected and it took me to some difficult, hard, grueling, horrible places where I didn't expect to go. But thanks to my wonderful wife, who I think is the hero of the story, we’re in a good place.

I'm a little nervous as one would be with any book, but I'm even more just because, as you said, it’s a pretty candid book. People sometimes have curious responses to candor. A lot of people, including friends who read it, sort of thought they knew me and now think, Ooh, you're different than you thought. That will in the end be great, but in the short run that sometimes leads to uncertainty or a sense that I've disappointed people or that I wasn't the person I said I was — and that is true. I wasn’t. If you want to see the person that I actually am, read the book.

Has there been any fallout from friends or family who have read early copies of the book?

One person who was close to me felt like, “Oh, I thought I knew you well, and I'm disappointed that I didn't,” but I think we've worked through that. That's a perfectly fair feeling. What I said to this person was, “It wasn't like I was keeping my secrets from you. I was keeping them from everyone, including at times myself.”

If you woke me out of a deep sleep I wouldn't have said, “Oh, here's the complicated person with a bit of a secret life.” I would've said, “No, here I am just being me.” I think that was tricky, but generally people have been appreciative. People who have read it seem to respond to the story, particularly men of a certain age respond. Everyone has a dad. A lot of people feel like the dads of a certain generation, they recognize some of the distance and some of the difficulty of communicating across the generations.

Do you think your dad would have liked the book?

It’s funny. A couple of people have said, “Oh, your dad would have really loved the book.” And I think that's a really nice compliment to hear. I feel like he might have loved it in about 10 years. (Laughs) It’s pretty candid about what I perceived as some of the ways in which he disappointed me and some of his general failings — many of which I share. I think at a certain point I decided I wrote him off and thought, I'm gonna be different and better and smarter and more emotional than he was. And then in the course of writing the book and making discoveries about him and making discoveries about myself, I realized actually, No, there are huge commonalities between us.

Like what?

I think I came to appreciate the ways in which he did like my writing and was a fan of it and a champion of it. I wish he'd been able to communicate that more emotionally and more directly, rather than through carefully composed letters to me that I could years later look back at and think, Oh, yes, he was moved by this. At the time it didn't come through to me. And that's because I'd given up on him in a certain way, and decided I wasn't going to get much more from him than rationality and logic and kind of slightly disapproving distance.

He would talk to me when I wanted to talk to him. He wasn’t the Great Santini by any means. He was doing his best. And I totally realize that now. It’s just that he had a shitty father, who was probably doing his best as a father but was very bad at it. And his father was sort of an alcoholic and a weak man. Just a sort of limp, passive figure. And my dad had to figure it out for himself. But when you're a kid, no one gives you the handbook to your own dad. All you have is what's in front of you. Only years later, do you sort of think, Oh gee, he had it tough, too.

Whenever I finish writing something, there's always more that comes after. Are you still working through feelings about your father? Are you still learning about him?

I've been thinking about that recently and I think you're absolutely right. I do feel that I'm still working through things. Just because someone dies doesn't mean the relationship with them is ended; it continues. My mom died 19 years ago and I feel differently about her now than I did a year after she died. I feel differently about my father. And, in fact, a friend of my parents recently sent me letters from each of them to her. In reading their letters to her, particularly my dad's, I saw aspects of him that I didn't know about, and it changed my feelings yet again after the book was done.

How so?

Because he was writing to me, he communicated in a certain way. When he wrote to her, a good friend of the same age, he conveyed his joy in writing in a way that I didn't see. I got more of a sense of strain and, like, I'm showing you this, please be sparing in your criticism. But I didn't get the sense of puppy-like joy that he conveyed to her. So I think it goes on, even if you don't get letters from friends that show you something. You get to a different age and then your kids get to a different age and you suddenly realize, Oh, here's this challenge that they handled in a certain way, and maybe they’re handling it better than I am now with my kids.

How do you want your kids to see you now?

I want them to see me as a dad, someone who loves them, someone who's fallible and has made mistakes and vowed never to make the terrible mistakes that I've made again. And someone they could talk to about whatever's going on in their lives. They’re 15-and-a-half. They're twins. This is probably not an age when all of those things are top-most on their mind. It’s not an age, necessarily, of heart-to-hearts. I hope that, in time, that will occur. I think every parent of a teenager knows that feeling.

In the book, you find a letter Day wrote to you that he never mailed. You write that he hid some things from himself and that you hid things from him. With your kids, how do you make sure they find you?

Well, they will eventually read the book and that will be a start. I try to live life out in the open, in the light. It’s a great question. All I can do is try my best. And I think that's both hopeful and probably a little bit melancholy because, as I said earlier, my dad was also trying his best. I wish I'd been able to understand him more fully before he died. Yes, the relationship can go on afterward, but it'd be a lot deeper if you could have two-way communication.

Your kids will eventually read this book, which details your history of infidelity, your struggles with Amanda, and your therapy with Day. You went through a trove of your dad’s documents and correspondence. Do you feel there are things children shouldn't know about their parents?

I think there are things that every parent decides when the time is right to disclose. When your child is waking up from a nightmare at age 3, you don't talk about your own nightmares. You sort of gauge the time and the place, but I would hope that in the fullness of time my kids would know all aspects of me. One of the great things I learned in the writing of this book is how fallible and not an expert in life I am. This book is in no way prescriptive to other parents or families. It's just simply my story and our family’s story. So I'm not going to wade into the terrain of what other parents should do. I think Amanda and I are trying to be there for our children, tell them what we think they need to know, and at the time they need to know it.

The one thing your book drills home is that there’s no quote-unquote normal family or perfect family.

A friend of mine, years ago said, the definition of a dysfunctional family is a family. Tolstoy famously said the thing about happy families are all alike and I think—it was implicit—not worth writing about. I can think of one seemingly very happy family that I know of that just seems unalloyed in its happiness. And I slightly fear getting too close to them because I would probably discover that there are the usual complications and difficulties and resentments and feelings. It’s hard to get the exact Goldilocks distance between people in a family where they know everyone feels perfectly loved, but also perfectly able to be themselves and not being pushed in some direction that they don't want to go.

There is tumult in families, but good can come out if you’re willing to dig to the other side.

My experience with my wife in basically betraying her, failing our marriage, and then having her be amazingly supple and generous and wise, and working with me, has been very hard for a year on our marriage. But I think we feel much happier now. And it’s better. It's been really hard on both of us, but particularly on her. Because I, at least, knew what I was doing, even though I kind of pretended to myself that I didn't. And she didn’t. She was blindsided and none of it was her fault. It was my issues. She could have said see you later, but she chose to accept me. Through a lot of hard work, I think most of the time we feel like we're doing better and we keep heading in the right direction.

There are certainly shitty days and it's not a Hallmark card. Years ago, I wrote a piece about The Larry Sanders Show, and I spent some time on the set there with the actor Rip Torn. He said, “I feel like I'm carrying around a big bag of yesterday.” And I think I felt that, too, until the process that we're working through where I feel like I’m just jettisoning secrets and compartments and vulnerabilities that I just kept hidden. Working through them, I feel like I’ve tossed the bag off my shoulder. I feel a lot lighter.

How do you do all of that and be an effective parent?

You do the work, not in front of them. We have a therapist who’s great. The rest of the time we're also talking to each other a lot and taking walks with our dog and working hard in the best positive sense. “Working hard” sounds like you're working in an Amazon factory, fulfilling box orders. There’s a pleasure to it. It is joyful labor.

About the kids, we’re doing our best, which isn't always the best every day as far as they're concerned. We’re getting them up for school and have conversations about the orthodontist and try to talk about how they're feeling and help them with their homework. And a lot of times they would rather do it all themselves. And that's what being a parent of a teenager is. There are definitely times when we remember them being five or eight and thinking it was so nice when they depended on us, believed everything we said and took our word as gospel. Now it's more complicated and we're all dealing with that. And then it'll be more complicated in a different way when they're 20 and 25. And I look forward to that.

Do you think the process of writing this book and everything after make you a better father?

(Laughs) Well, the assumption is that I'm a better father. I don't know. I hope I am. I feel that being very aware of my own feelings is helpful. I think the unexamined image that a lot of us have as a father is sort of a distant authority. I don't feel distant from myself anymore, and I don't feel like an authority. That, I hope is better. I'm not totally convinced of that, because it's all happening in front of us every day.

I feel like in the course of writing the book and kind of living the life that the book recounts, I came to appreciate how similar I am to my father. One big difference is he was much more emotional, much more vulnerable, much more passionate, much more sensitive than I understood. And that came out only after he died when I was going through his journals and letters and papers. I hope I don't have to die to have my kids realize that about me—that they will feel that way just in the course of living with me, talking with them. You'll have to ask them in another 20 years whether I'm right or not.

The book is a great reminder that as you get older, you’re still fallible. You’re still learning. There’s no moment when you sit down with the wise elder who unfolds the secret to life. We’re hurtling through space, doing the best we can.

I totally agree. I feel much more that way than I felt a year or two ago when I sort of secretly, smugly thought, Hey, things are going pretty well. I know what I'm doing, I'm right about most things, if not everything. And now I sort of think I'm probably wrong about most things, and maybe I should listen to other people.

That's quite a different approach. When I am listening to other people and hearing what they have to say, it feels great. One of my favorite lines from The Philadelphia Story, the Katharine Hepburn character says, “The time to make up your mind about people is never.” I think that feels right to me that you do keep absorbing and changing. Let’s keep listening. Let's keep learning. Let's keep open the lines of communication and the lines of judgment soft.

Do you think we're ever free of our parents' influence, that we can just be our own person?

(Long pause) I think that's the goal. It’s like an asymptote where you’re always striving for it. If you're Rousseau’s wolf child born in nature, you'd still be thinking, Oh, there's my wolfish quality. Whether it’s nurture or nature, it's hard to escape those influences. When I look in the mirror or wince in a certain way or when I sneeze very, very loudly — which my dad also did — that's my dad and he's inhabiting me. I think the way toward freedom is to not rebel against those influences that are so strong. I don't think you can ever be free of them. Maybe being free of them is not really the goal. It's just simply accepting those influences, trying to understand them as fully as possible, and then deciding what you want to do with them.

Freud said something that always stuck with me: He said life is too much for us. If you’re thinking, That’s right, life is too much for us. It's really hard. Everyone's doing their best, that's not a terrible way to open the door to your house to go out into the world.

This article was originally published on