What I Learned When My Son Was Diagnosed With An Eating Disorder

It's never easy.

The following was syndicated from Quiet Careers for The Fatherly Forum, a community of parents and influencers with insights about work, family, and life. If you’d like to join the Forum, drop us a line at TheForum@Fatherly.com.

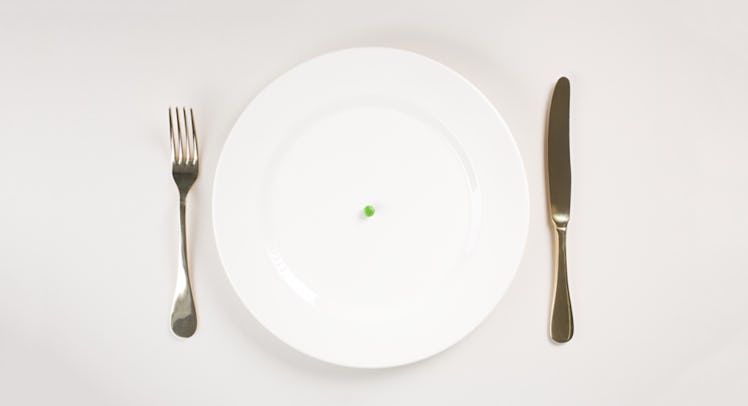

When my 17-year-old son was diagnosed with an eating disorder, it happened without warning. I liken it to getting hit in the head with a 2×4: I didn’t see it coming and it knocked me flat. The months following his revelation were some of my darkest, and they were also a time when I learned more about myself than perhaps any other time in my life.

I wanted to pick apart everything about his treatment, micromanage it and find fault with anything and anyone besides myself.

I sat across from my son’s therapist during our initial meeting, resenting her barely moments after I met her. “What does this Barbie doll know about my son?” I thought arrogantly. Everything she said grated on my nerves, like fingernails on a chalkboard. I hated the way she said “behaviors” to refer to bingeing and restricting food, often using air quotes.

I didn’t like how she called me “Mom.” “I’m not your mom,” I wanted to shout (even though I knew what she meant, how she was using shorthand to include me in the conversation). “Take the time to learn my name,” I wanted to yell at her even though that detail was the most irrelevant thing in our conversation. Somehow, harping on it gave me something concrete to hold onto, something I could criticize someone else (besides myself) for.

She interrupted me as if what I said wasn’t important (excuse me, am I not the person who knows my son best?!). I felt like a visitor to a foreign country, disoriented, grasping for landmarks and direction.

Mercifully, I bit my tongue. I never actually yelled at her (except in my head). Instead, I asked terse, concrete questions, and I exited quickly, leaving my credit card number and insurance information with the receptionist at the treatment center.

Some part of me knew that my son had his own relationship with his therapist, that I didn’t get to construct or script it, and the biggest contribution I could make to his healing was to not sabotage his therapeutic alliance with her, not matter how much I wanted to be right about her being poorly suited to help him.

Later, I realized that I was deflecting a volatile cocktail of my own emotions: Blame and anger, guilt and shame. It was easier to pick her apart, to find fault with her clinical skills, to shoot her down as a poor match for my son, to claim he was special and needed something else — that was easier to looking my own shame in the eye.

“This is the person I’m rowing with,” I thought about my son’s therapist. “We’ve got to row in the same direction.”

I let my objections stay. I watched myself resent her beauty and her youth and her mannerisms. I didn’t beat myself up about how focused I was on picking her apart, but I also didn’t act from those observations and impulses. I harkened back to learning how to meditate. That was when I was introduced to the idea that thoughts can be observed like clouds in the sky, passing overhead with some detachment, no need to react to them. “Don’t mistake the weather for the sky,” become my mantra.

I wanted to pick apart everything about his treatment, micromanage it and find fault with anything and anyone besides myself.

I grieved the relationship I thought I had with my son, and I turned towards co-creating a new relationship with him.

“This is not my son,” I thought, my brain rejecting what he was telling me. My son doesn’t hide things from me. He’s not losing massive amounts of weight without my noticing. He’s not so lost that he has veered away from us.

It was like someone told me the sun rose in the west. “No, it doesn’t. It doesn’t,” my brain insisted. Even as irrefutable evidence stared me in the face.

Who was this person in front of me? Where was the baby I nursed? The toddler I bathed? The child I read bedtime stories to? The adolescent I drove to school? Where was he? Because that person, the one I clung to in my mind, was gone, replaced by the body snatchers when I turned my head. And I had only looked away for a moment. Somehow I had blinked, I let my attention stray, and I didn’t see him slip away.

I let myself sob. My son held my hand as he confessed how he had spiraled downward into a dangerous eating disorder in the past months. And I turned to face the person who was sitting in front of me, opening himself up for me to see.

“This is where we begin,” I thought.

I had to learn how to manage my own guilt and anxiety.

In the months following my son’s diagnosis, I slept very little. I had a laundry list of physical symptoms that pointed directly to stress and anxiety. I raced to a therapist and scrambled to line up treatment for myself: neurofeedback, a prescription for Xanax, another for Lexapro, meditation, yoga, daily exercise.

It was like someone told me the sun rose in the west.

Ironically, as my son was healing, climbing out of his hole, I slid downward, belatedly experiencing my own guilt, sadness, and pain as my son’s trials of the past few months surfaced, and I recognized how much I had missed about his struggles and pain. Cue massive guilt with a volatile twist of anxiety.

I learned some tough lessons in those dark months:

- I could not turn to my son to absolve me of my guilt. I had to work that out on my own with the help of my therapist and coach.

- There’s a difference between experiencing emotion and reacting to it, and understanding this distinction took massive patience and practice.

- I leaned heavily on a practice called “mental hygiene,” where I excavated my own underlying beliefs, bringing them to the surface so that I could dissect how they were fueling my runaway anxiety.

Look, I know it sounds dramatic, and that’s okay because it still feels true. If I didn’t learn how to recognize, turn towards, and manage my own fear and guilt, it would have run me over like a Mack truck. It still knocked me down, left me reeling, and sometimes chewed me up.

I remember when my coach asked me what was good about my son’s downward spiral and diagnosis. I really couldn’t compute that question, and it took me a while to find the silver lining. It’s here, though.

His pain, struggle and dip into blackness challenged me to really learn to take care of myself. It provided a doorway for me to wade into my own darkness and do my own healing. I would say that it woke me up. It was a harsh wake-up, like the sound of a fire alarm going off in the middle of the night, disturbing and traumatic, but something that cannot be ignored. I couldn’t go back to sleep, couldn’t return to complacency, afterward. For that, I’m grateful, and I’m turning to face forward.

Maggie Graham is a career coach with a morning journaling ritual that sometimes turn into blog posts. She lives in Fort Collins, Colorado, a sweet town where the plains of rural farmland meet the foothills of Rocky Mountains, with her husband, two teens, an angelic dog, and a perpetually grumpy cat.

This article was originally published on