Me, My Daughter, And The Marquis de Sade

I wrote a book about the notoriously taboo (and often criminal) Marquis De Sade. So what did I tell my daughter?

For the most part, kids aren’t especially interested in what their parents do for a living. Especially among elementary aged kids, the most salient things they know about what Dad does are a) it’s boring and b) it cuts into our playtime. But when you need to hide what you do, children can smell it. Their curiosity awakens. I learned this the hard way.

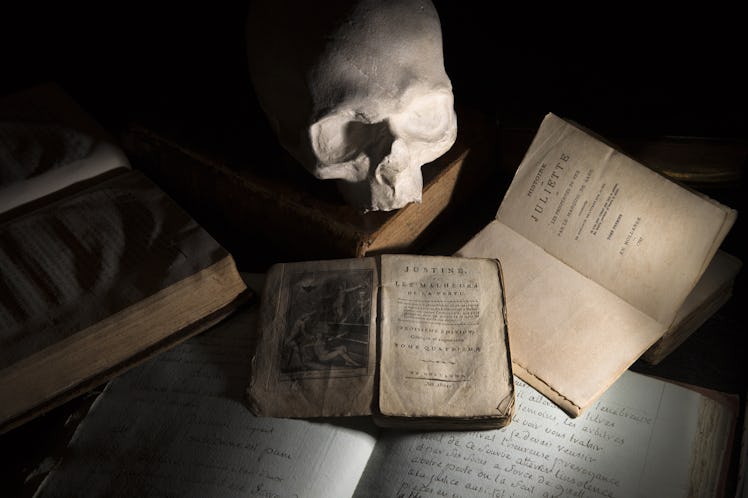

Four years ago, I began working on a book on the saga of 120 Days of Sodom, an obscene manuscript considered by many to be the worst (as in most vile) thing ever written. Penned by the notorious Marquis de Sade, the scroll endured a continent-spanning odyssey that involved underground erotica collectors, pioneering sex researchers, violent riots, explicit art, mass murderers, and most recently, allegations of a giant literary scam. In other words, not the sort of things you like to mention when your kids ask about your day.

I tried to be sly about it. Working long hours in my home office, I hid all Sade reference books with explicit covers when the kids nosed around. On a research trip to Sade’s various chateaus in France, I steered the family away from references to the Marquis’ degenerate habits and obscene literary output.

I wasn’t as sneaky as I thought. When her third grade teacher asked me to come to class to talk about my job, my nine-year-old daughter Charlotte looked up at me with plaintive eyes and said, “Dad, please don’t talk about the Marquis de Sade.”

Clearly, my daughter knows more about the namesake of “sadism” than your average kid. But does she know enough to get her (or, more likely, me) in trouble, leading to a worried call from a teacher? I aimed to find out by asking Charlotte exactly what she knows about the Marquis De Sade. The answer: More than I thought, but not in a bad way.

Here’s what she had to say:

1. “The Marquis de Sade was not a nice guy. He probably did some, like, misogynistic things.”

This is true! Born in 1740, the French aristocrat engaged in blasphemous acts with a prostitute, tortured a beggar, poisoned whores, locked his servants in a castle for his own devices, and seduced his sister-in-law — and that was all before he turned 40. Thankfully, Charlotte didn’t learn about any of this stuff, but she gets bonus points for using a big word like “misogynistic.”

2. “Sade has something to do with ‘sadistic,’ but I am forgetting what that means right now.”

Right again. Thanks to his writing and behavior, Sade became so deeply associated with cruelty that after his death he inspired the term “sadism” — deriving pleasure from pain. So every time you use the word “sadistic,” you’re referring to a randy old Frenchman.

3. “He was killed.”

Incorrect. The Marquis de Sade wasn’t killed, but not for lack of trying. He was independently imprisoned by the last pre-revolutionary king of France, the architect of the Reign of Terror, and Napoléon Bonaparte, but ended up outliving nearly all of them. A natural escape artist, he broke out of prison, dodged a military raid on his home, absconded from a police squadron, and twice eluded his own execution. One time, when executioners couldn’t find him, they hung a Sade mannequin instead, which is apparently something folks did back then.

4. “He wrote a lot of not nice books. His most famous book was 101 Days of Sodom.”

Charlotte is likely confusing Sade’s novel 120 Days of Sodom and One Hundred and One Dalmatians – which is understandable, since both have a mean streak. Once finally locked away, Sade became obsessed with writing, producing numerous obscene works that culminated in 120 Days of Sodom. Penned on a 40-foot scroll in the notorious Bastille prison, the novel tells the story of four wealthy degenerates who lock young subordinates in a castle and subject them to four months of escalating depravity. Sade declared it “the most impure tale ever written since the world began,” while others called it the “gospel of evil.” I’d rather Charlotte know about Dalmatians.

5. “The scroll was passed around and stolen a lot. And they say it’s cursed. If you touch it, you’ll be set on fire and disintegrate into a giant nose.”

I am pretty sure Charlotte was joking about the immolation/nose stuff, but other than that, she’s correct. Due to the upheaval the scroll left in its wake as it crisscrossed Europe — crushed dreams, ruined fortunes, Nazi book burnings, violent riots, an audacious heist, and international court battles — some authorities, including a direct Sade descendant, believe the manuscript is cursed. It doesn’t help that when the scroll returned to France in 2014, it landed in the heart of the largest alleged Ponzi scheme in French history, rocking the world’s most celebrated book market to its core. Am I worried about the curse, considering I wrote an entire book about the scroll? “Nope!” I say with a nervous chuckle.

6. “Kids should not read your book. It’s appropriate for older teens and grownups, if that’s what they’re into.”

While I’d love everyone to get my book, The Curse of the Marquis de Sade: A Notorious Scoundrel, a Mythical Manuscript, and the Biggest Scandal in Literary History, Charlotte’s right. While I steer clear of the explicit stuff in 120 Days of Sodom and focus on the people and events connected to the scroll, it’s not the best option for toddler bedtime stories. The book is better left for when you have alone time and looking to dive into a twisted true tale — that is, as Charlotte says, if that’s what you’re into.