25 Years Ago, One Episode Ended A Perfect Era Of TV

Before the internet, Siskel and Ebert was how Americans figured out which movies to watch.

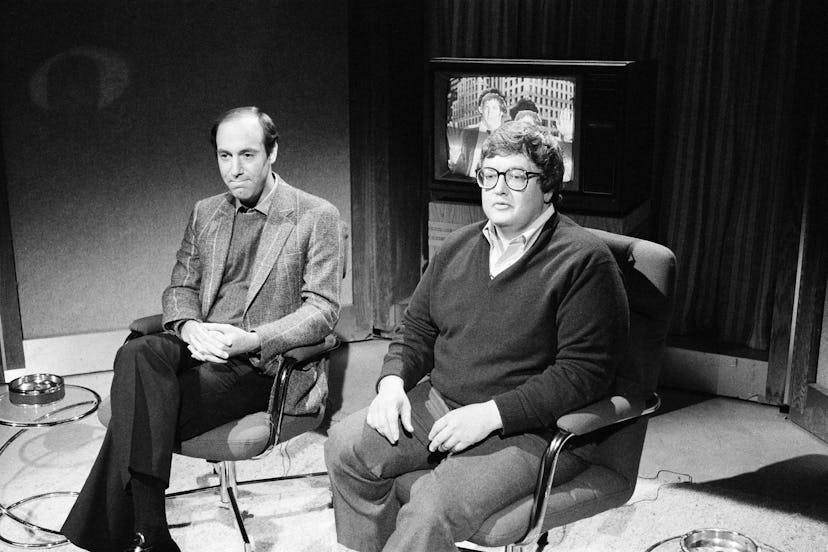

Siskel and Ebert were bigger than the movies they reviewed. For over 20 years, their voices informed Americans what to see in theaters, and dominated the critical landscape. Films thrived or crumbled by the direction these powerful Chicagoan’s thumbs pointed. But on Jan. 23, 1999, that changed when these larger-than-life critics arrived on set for what would be their final taping together. Nobody was prepared for what would happen after the cameras stopped rolling, and even fewer knew the truth.

Today, opinions about movies are everywhere. But when Gene Siskel and Roger Ebert began their TV show in 1975, it was downright revolutionary. A new concept was born — two critics discussed a film face-to-face. But the real magic began when they had opposing views, degrading from a friendly chat into drag-down verbal sparring matches.

Neither was fond of the other in the beginning, and everything was a point of contention, including chair cushions, lunch orders, and even who sat down next to the host during late-night TV appearances. Over time, this dysfunctional pair developed a mutual respect for the person they once considered their greatest rival, and maybe something more. Unfortunately, the curtain came down sooner than either expected.

Who were Siskel and Ebert?

Gene Siskel and Roger Ebert were young hotshot film critics for rival Chicago newspapers, always at odds from a distance over who was the best in town. They reluctantly joined forces at the suggestion of a TV producer, interested in trying a new style of movie review on public television. To say they had a rough start would be like calling Wrigley Field just another ballpark, but once the ratings came in, they knew they were onto something special. It just took some time to figure out how to get there.

As Matt Singer explains in his fantastic new book, Opposable Thumbs: How Siskel & Ebert Changed Movies Forever, initial TV tapings were laborious and overly rehearsed, requiring an eight-hour workday to complete a single 30-minute episode. Their petty arguments frequently ground production to a halt. After one miserable session led to a producer storming off set, an intern jumped in and realized all Siskel and Ebert had to do was spontaneously converse and argue with each other, and the show instantly became more tolerable to record and better to watch (that intern, Nancy De Los Santos, became the show’s producer not long after). The discord in their discourse simply made for great television.

What started as a monthly PBS show became a weekly syndicated sensation by 1982. Four years later, the series was picked up by Disney, where the distributors signed a deal guaranteeing the critics wouldn’t be forced to show bias toward the Mouse. People around the country tuned in to see the showdowns but stayed for the insight, knowing that would devolve into a fight, too.

Why were Siskel and Ebert so awesome?

The reviewers’ status grew beyond their show. Entertainment Weekly ranked them as the 10th most influential people in 1990, appeared together on Sesame Street to instruct Telly and Oscar the Grouch how to critic, and became mainstays on talk shows, with Siskel and Ebert flipping a coin to decide who sat closest to the host. They were the critical versions of Laurel and Hardy, and no one grew tired of their act. They were as entertaining as they were trustworthy, never afraid to tell how they really felt about something. It scared movie studios and endeared viewers.

Audiences were attracted to it in the same way ’90s kids watched The Jerry Springer Show when they were home sick from school. These strange bedfellows fought tooth and nail to prove their point and intellectual superiority. Both had hills they refused to come down from despite the other’s bereavement. Ebert could appreciate campy schlock like Return of Swamp Thing or sappy kids movies like Free Willy, while Siskel seemingly held every piece of film to the same standard as Peter Bogdanovich or Akira Kurosawa.

One of their defining moments happened in an episode from June 1987, when the quarreling critics butted heads while reviewing Stanley Kubrick’s Full Metal Jacket. Ebert found it cliched and derivative of Platoon, while Siskel considered it among the year’s best films. The intense crosstalk continued into their discussion of Benji the Hunted, where Siskel accused his partner of “wrapping himself in the flag of children” for liking the picture, and Ebert rebutted by saying Siskel was holding a kid’s movie to implausible adult standards, spilling into their last segment discussing video releases of other Kubrick masterpieces.

Always delighted to jab each other, whether it was for real or for the enjoyment of a studio audience, over time Siskel and Ebert learned to tolerate, respect, and even appreciate the person bickering across the faux balcony. In one instance, Ebert came to his partner’s defense during his public bout against the Chicago Tribune when his job as a critic was in jeopardy, going as far as pitching the editors at his paper to bring Siskel in to share the coveted movie review spot. The move ultimately didn’t happen but was surely one Siskel appreciated from his best frenemy.

The Final Days of Siskel and Ebert

Days after an appearance on The Tonight Show where the Tribune writer seemed uncharacteristically out of sorts, Gene Siskel was diagnosed on May 8, 1998, with terminal brain cancer. No one, including Ebert, knew how severe the situation was outside of his immediate family.

Neither host had missed a taping before, and Siskel refused to start now, calling in to do the show a month after an operation removed a growth on his brain. Siskel’s rapport with Ebert wasn’t quite the same once he returned to the set. His speech was slower and a little clunky, and he squabbled less with Ebert than in years prior. His final episodes revealed a man coming to terms with his fragile mortality. Suddenly, movies he might have panned for being maudlin became revelatory experiences, like his profound thoughts on Meet Joe Black, exposing a vulnerable side from the ordinarily private critic.

As Singer’s book describes, it was business as usual heading into what would be Siskel’s final episode, recorded in early January 1999 to air on the 23rd. While the two previously sparred over who came to set first to avoid waiting for the other, Siskel asked to be seated before his partner to hide his diminishing mobility. Theory of Flight became their final joint review, and it made perfect sense their last moments on camera together would end on opposing sides of the aisle — Siskel with thumbs up, and Ebert’s pointed down. There was no grand farewell speech at the end, as neither knew this would be the final taping they would complete together.

A week later through a press release, Siskel announced he was taking a “leave of absence” to heal ahead of the fall ’99 season premiere. He passed away 17 days later on Feb. 20 at 53 years old.

Publicly, Ebert offered gracious speeches about his departed friend, but privately lamented the man he spent over two decades sitting across from never divulging what was happening to him. The memorial episode of their show placed their greatest battles and funniest moments on display, including a message from Ebert who answered two queries at once — the question Siskel asked everyone he interviewed on “What they knew for sure,” and whether the two truly despised each other: “People always asked if we really hated each other. And one thing I know for sure is that we didn’t.”

End of an Era

The remainder of the season and year that followed ran through a Rolodex of floating guests, eventually landing on Richard Roeper to be Ebert’s new co-host. While the camaraderie was strong, gone was the friction between clashing critics that fans loved to watch.

In February 2002, Ebert announced his cancer diagnosis and began an arduous battle against the disease that he never physically recovered from. Forced to endure a tracheostomy to help him breathe and eat, and unable to speak after part of his jaw was removed in 2006, Ebert’s partnership with the series concluded in July 2008. The show ended in earnest after disappointing runs with different hosts on Aug. 14, 2010. Even as cancer ravaged his body, Ebert remained sharp as ever and connected with a new audience through Rogerebert.com.

One day after writing his final blog post to announce a hiatus while he dealt with worsening health issues, Ebert passed away on April 4, 2013. He concluded his entry with “I’ll see you at the movies.” He wasn’t wrong, as a documentary filming his struggles chronicled him on the big screen titled Life Itself, named after his memoir published seven months earlier. His website continues to this day as a haven of reviews for media including film, TV shows, and web series.

Years after they passed, the names Siskel and Ebert remain synonymous with criticism. Growing up in the ’80s and ’90s, this pair of star-crossed Chicago journalists was the authoritative answer to what movie was worth watching, and while the internet has no shortage of reviewers now, none come close to the heights Siskel and Ebert achieved. Until that happens, the balcony is closed.

This article was originally published on